For all the talk about the pace of the clean energy transition in Australia’s main grids, perhaps the most remarkable transition is starting to take shape in the north-west of the country, in the heart of Australia’s iron ore riches.

The Pilbara region has made fortunes for many people. It has turned Gina Rinehart and Andrew Forrest into the two richest people in Australia, and been the backbone of earnings for two of the world’s biggest mining groups, BHP and Rio Tinto.

Renewables, to date, have barely scratched the surface in this region – one 60 MW solar plant is operating and a couple of others are under construction in a region with 2,800 MW of gas and diesel capacity. There is one big battery in service, which is making money by reducing the need for one of the region’s biggest gas plants to have its own back-up gas generators.

This is a world dominated by gas and diesel, but both these fossil fuels are costly and dirty, and in the next decade the miners – well, most of them – know they have to switch to cleaner and cheaper alternatives, because it’s cheaper and because their customers demand it. Some, like Fortescue Metals, are in a big hurry and want to do this by 2030.

And despite the presence and influence of Rinehart – pro nuclear and profoundly anti-renewables – wind, solar and storage are the chosen options for the iron ore giants’ future power generation needs, along with electric and possibly hydrogen trucks for their transport and mining equipment.

Listed infrastructure and energy group APA, which recently took over the Pilbara network and generation assets of Alinta Energy, last week gave an interesting presentation to visiting analysts about the scale of the transition that is happening in the Pilbara.

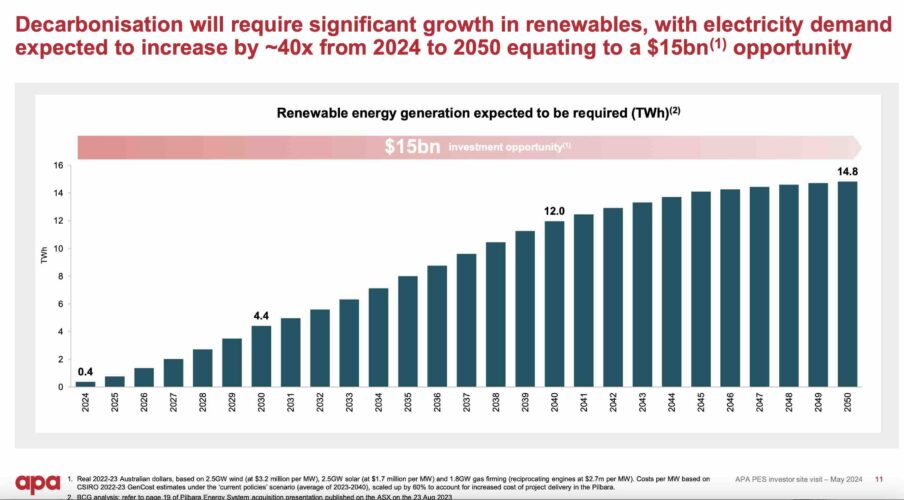

According to APA there is just 0.4 terawatt hours (TWh) of renewable generation going into the region’s networks and mines right now, but this is expected to jump 10-fold to 4.4 TWh by the end of the decade, and treble again to more than 12 TWh by 2040.

It could happen quicker than that, particularly if the other majors follow in the footsteps of Fortescue’s goal of reaching “real zero” emissions (i.e. burning no fossil fuels) by 2030.

There is a fair bit of work to do. The Pilbara iron ore region is almost feudal in its set up, with most miners having their own train lines to transport the ore to port and their own electricity networks and own generation assets.

They are being encourage to share and join forces, with the local utility, government and private operators, and this is where APA sees a role for itself as a key linch-pin in a renewable-dominated future.

See our story: Mining giants agree to end feudal energy grids and create massive renewable hub.

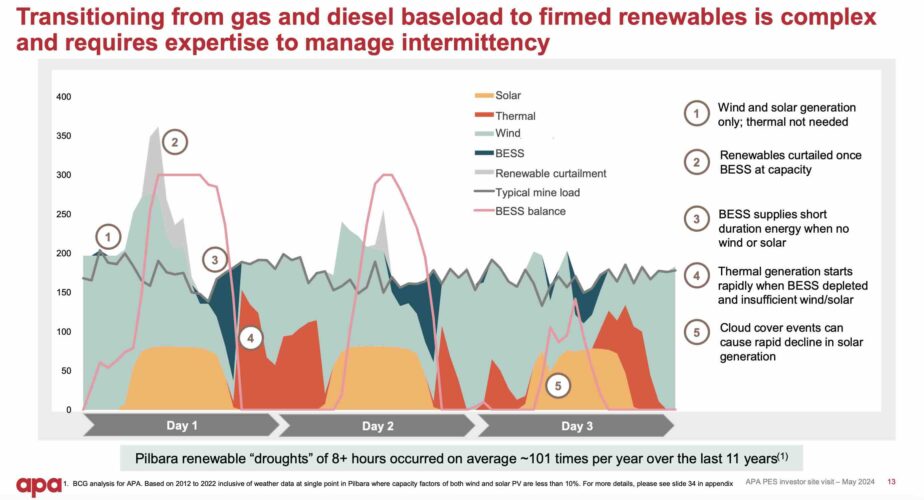

Having achieved a united energy network, it will be another task to manage a remote, isolated grid with a high level of renewables – although many smaller, isolated mining operations have shown how that can be done.

As for APA, it plans more than 1.6 GW of wind, solar and storage in the near term. It is building the 45 MW Port Hedland solar farm and the nearby 35 MW, one hour battery. It will then look to expand those facilities, as well as the Chichester solar farm, before adding the region’s first large scale wind projects at Chichester, Newman and Shay Gap.

APA notes that the 60 MW Chichester solar farm provides up to 100 per cent of the daytime energy needs of the Chichester hub, but according to its calculations more than 30 per cent overall solar share results in more curtailment and more storage than is economic.

Adding wind, it says, will allow deeper renewable penetration and further reduce cost of energy and CO2 emissions. The balance of power is then delivered by gas. The graph above shows the gaps that APA expects that gas generation will fill (in red)..

APA is, after all, essentially a gas infrastructure company. Experiences at other stand alone mining sites where demand management is also highly rated as a cheap and effective part of the energy system may lead to further refinements in how the company sees the energy future.

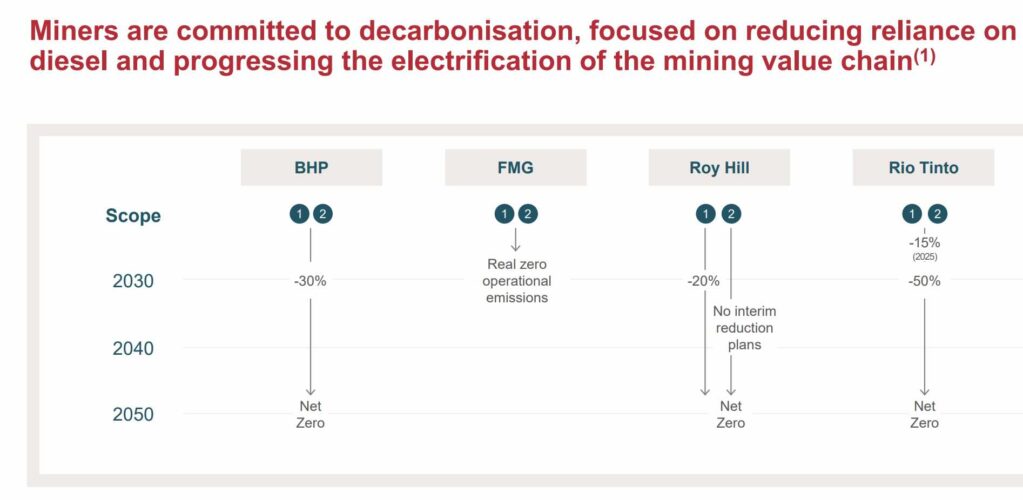

But how keen are the big miners to actually do this? Fortescue is absolutely engaged, and is trialling electric and hydrogen alternatives for its giant haul trucks, electrifying its giant excavators to deliver massive diesel fuel savings, and developing its own battery technology and its “infinity” train, as well as its own solar, wind and battery projects.

BHP and Rio are also co-operating on the development of battery powered haul trucks at their mine sites, and both companies are talking about large investments in wind and solar projects.

Rio is already in the hunt for wind and solar contracts for its giant smelters and refineries in Queensland and NSW, and BHP has signed a “renewable baseload” contract with Neoen for its giant Olympic Dam mine in South Australia and has started the search for half a gigawatt of renewables and storage in the Pilbara.

According to the APA presentation, Fortescue leads with its “real zero” target for 2030, while Rio Tinto has a 50 per cent emissions reduction target by 2030, and BHP has a 30 per cent reduction target. Rinehart’s Roy Hill mine trails the field, with a 2030 target of just 20 per cent, and no interim target. Perhaps it is waiting for SMRs to become a thing.