The Department of Defense has 7,600 military installations across all 50 states and 40 foreign countries. They perform diverse functions, but they have one thing in common: climate change could cost them big in the coming decades unless adaptation measures are taken soon.

The military has already taken some action. Planning for climate change impacts is being folded into base Master Plans around the world. And renewable energy projects have popped up on a few installations, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and providing power separate from the grid.

Given that the DOD owns and manages a real estate portfolio worth $850 billion, these are big steps.

Beyond the walls of its bases, the Pentagon has also recognized that climate change presents a threat to national security and is looking at options to address changes already taking place.

A recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) report chronicled how climate change is affecting some military installations in the U.S., from the tundra to the coast to the desert. The report found that while some actions are underway, there are still roadblocks to preparing for future changes at the base level in a timely manner.

The GAO report outlined five main climate impacts that military installations will have to deal with: hotter temperatures, changes in precipitation, rising sea levels, increasing storm frequency and intensity, and changes to the ocean’s chemistry and temperature.“DOD has over 500 major bases but nearly 7,600 sites worldwide. Theoretically any one of them or all of them are vulnerable to climate change,” said Brian Lepore, the head of GAO’s defense capabilities program, which authored the report.

Documenting their impacts at all installations would be a monumental task, so for the purposes of the report, 15 installations in the U.S. were analyzed, though the authors stressed they weren’t necessarily meant to be a representative sample. Yet of the 15, all have already seen climate-related impacts or were aware of future ones.

Climate Impacts Already Visible

In some cases, the results were dramatic and visible, particularly in the Arctic, where the effects of climate change are magnified. A rise in temperatures, which has been twice the rate as the rest of the globe, has thawed permafrost. That has literally opened holes in the ground in areas typically used to train troops in conducting air drop and parachute drills.

At a radar station along the Alaskan coast, the coastline has receded by 40 feet thanks to a combination of melting permafrost, the disappearance of sea ice, and rising oceans. That, in turn, has destroyed parts of roads and runways, reducing the accessibility of the station.

The increase in heavy downpours from 1958-2012 in each region of the U.S.

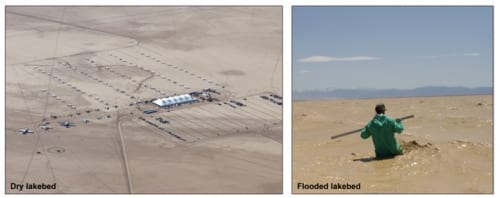

There are other extreme weather events that, while not directly tied to climate change, are indicative of expected impacts and trends. At Fort Irwin located in the Mojave Desert of California, a heavy downpour in August 2013 dumped a year’s worth of rain in 80 minutes, causing $64 million in damage. Every region of the U.S. has seen increases in heavy downpours since the 1950s, a trend that’s expected to continue.

Sea level rise also has the Norfolk (Va.) Naval Shipyard considering how to keep its dry docks, well, dry. Since 1930, the ocean has risen about 15 inches in the region, double the global average, thanks to a combination of sinking land and rising waters. That rise has increased the odds of storm surge reaching the docks where ships and submarines need to be kept dry for repairs or modifications. Any flooding could set back those repairs weeks or months and it has the base considering whether to build a new sea wall to keep stormwater out.

Planning for Those Impacts Is Still A Challenge

While climate change is an issue that’s not going away for military bases (or the world for that matter), planning for its impacts is still fraught with impediments. The DOD is conducting a review of all its facilities to identify vulnerabilities starting with more than 700 coastal installations because they’re at the intersection of a handful of climate issues, from rising seas to more intense storms and storm surge.

“Sea level rise is certainly something people have been talking about for awhile so it’s an obvious place to start,” Lepore said. “It’s pretty easy to measure and the Navy is doing that at its installations already.”

That’s a good start, but the GAO report found that there’s no plan or milestones in place to ensure that the review gets finished in a timely manner.

And once vulnerabilities are identified, there’s also no easy way to request funds for projects that would help reduce the risks posed by climate change or a centralized place to find out about local climate risks. Lepore said the recently released National Climate Assessment is a good source of information, but it’s not enough.

Base planners need more granular information. It’s not enough to know that hurricanes are likely to increase intensity; planners want to know if they need to build roofs to withstand 100 mph winds or 120 mph winds.

“When we talked to installation master planners, what they told us is that they’re aware of potential impacts from climate change and they know they need to do something about it, but just giving them ‘vague’ guidance — more droughts, more severe storms — doesn’t tell them what to do,” Lepore said.

The other obstacle to overcoming climate planning challenges is the infrastructure funding process itself. Military bases have to submit bids for projects with their justification for why the project should be funded. But DOD currently doesn’t consider adaptation explicitly in its current project review process, giving base planners little incentive to include these types of projects in their funding requests.

Of the 15 sites GAO surveyed, 14 of them hadn’t submitted a climate change-related project because they don’t think it would be funded for this reason.

Ultimately, these are all fixable problems.

“In our view, while DOD has made progress, we thought there were a few areas where they have a little more to do,” Lepore said.

That includes setting a timeline for evaluating vulnerabilities and putting climate information in a centralized place for planners to act on according to the report. GAO also recommended defining key climate change terms as well as considering climate change adaptation as viable infrastructure projects.

Those changes are small steps, but they could get the DOD on track to keep its $850 billion in infrastructure operating smoothly around the globe.

Source: Climate Central. Reproduced with permission.