Good news! Earlier this week, scientists announced that the hole in the ozone layer has stopped growing.

The news comes almost three decades after every member of the United Nations signed the Montreal Protocol, a treaty to curb emissions known to damage the atmosphere.

Some have argued that the protocol’s success shows what can happen when governments put their minds to tackling major environmental problems. Why, they ask, can’t politicians do the same thing for climate change?

The question has been posed many times, most recently by the Guardian’s George Monbiot. Yesterday, he called on politicians to show the same “political courage” they did back in 1987. If they do, maybe the world will at last see some tangible progress towards cutting emissions and curbing global warming, he argues.

But is political will the only thing stopping politicians establishing a comprehensive climate treaty? We explore the obstacles to creating the equivalent of the Montreal protocol for climate change.

Complex science

The Montreal protocol and international climate agreements are similar in as much as they both try to address problems in the atmosphere identified by scientists.

But the relatively simple impact of emitting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) on the ozone layer may have made the issue easier for policymakers to engage with than climate change.

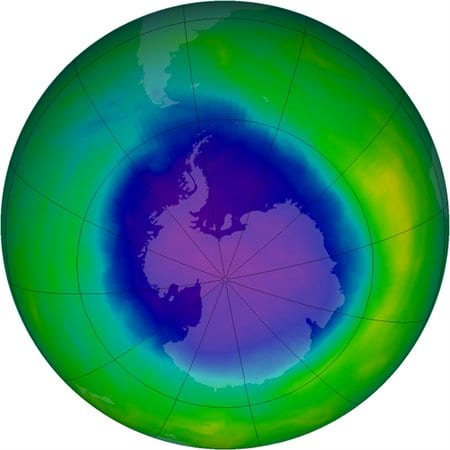

In CFCs case, it was clear their use was creating a hole in the atmosphere and scientists could present this in a simple, startling way:

But when it comes to climate change, the impacts are more complex. Greenhouse gas emissions cause multiple impacts across the world at different times. It’s an environmental challenge that encompasses the whole planet.

Dr Hugh Dyer from Leeds University’s school of politics and international studies says the ozone issue’s comparatively narrow focus meant there was “less opportunity for scientific uncertainty” to infiltrate the political negotiations than in climate debates.

Dr Hannes Stephan, lecturer in environmental politics and policy at the University of Stirling, agrees. He claims climate science is “such a complicated system that we’ll always have some surprises”, leading to scientific contestation. “That contestation is not a problem within science, but translating it in the political arena is complicated”, he says.

That may be particularly true when there’s as range of vested interests trying to ensure the core scientific message gets muddled. As a consequence, the “ozone hole sounds much more threatening to [politicians] than climate change”, he argues.

World politics

While science necessarily informs international climate negotiations, it’s not enough to deliver an agreement. Past experiences show that politics is also paramount. And a lot has changed in almost 30 years.

The Montreal protocol was agreed at a time when the US was considered to be the world’s dominant superpower. That allowed the US, which was in favour of curbing CFC emissions, to cajole other countries into taking action, Stephan says.

This is no longer the case. In the international climate negotiations there are at least four major players that don’t see eye to eye: the US, China, India and the EU. The lack of a global hegemon has arguably led recent climate negotiations to grind to a halt, with the US and China in particular waiting for the other to make the first move.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which determines the rules of the climate negotiations, also allows smaller countries to disrupt proceedings. The UNFCCC’s requirement that all countries agree to a new treaty means multiple voting blocs have formed, each with their own competing demands.

There was some political conflict over the Montreal Protocol, with developing nations arguing that they wouldn’t be able to afford to phase out CFCs. But this was largely overcome by countries adopting a financial mechanism to help poorer countries comply.

Countries established a similar Green Climate Fund in 2009 to help developing nations cope with the impacts of climate change. But the fund is almost running dry, with developed countries reluctant to make significant pledges.

So the Montreal protocol’s politics were a lot simpler, and the sums of money involved much smaller, than in international climate negotiations. That potentially allowed swifter progress, Stephan argues.

Ready alternatives

When it came to fixing the ozone, perhaps the biggest difference was that scientists had the advantage of being able to present policymakers with an immediate alternative. Hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) were known to be able to do the same job as CFCs.

The same cannot be said of climate change.

While low carbon energy sources like renewables and nuclear can replace fossil fuels to an extent, it’s not a simple like-for-like switch. Decarbonising transport, industry, and agriculture also presents a range of challenges to which there are currently no straightforward solutions.

So while “ozone depletion could be agreed and acted on with limited costs and limited complications”, Dyer says, emitting greenhouse gases “remains linked to our ways of life”. That makes persuading people to act on climate change a lot harder than simply switching one set of chemicals for another.

Rose-tinted view

With what we now know about the difficulties of agreeing a global climate deal, delivering the Montreal protocol perhaps looks like an easy feat. But “despite the favourable conditions, it still took considerable negotiating skill”, Stephan says.

Given the additional complications climate negotiators face, it’s possible the optimism that comes from seeing the Montreal protocol’s success is “misplaced”, he argues.

There’s likely to be some form of international agreement on climate change in the future. But the issue’s inherent complexity perhaps makes it unreasonable to expect politicians to deliver the climate-equivalent of the Montreal protocol, even if there were the political will to do so.

Source: Carbon Brief. Reproduced with permission.