One of the largest photovoltaic solar farms in the Southern Hemisphere has been approved to be built in South Australia.

Work is expected to begin on the Solar River Project in early 2019 with completion of the 220MW PV array and 120MWh lithium-ion battery in Stage 1 planned for the end of that year.

Stage 2 – with a minimum of 200MW of generation and a 150MWh battery – is planned to begin construction in early 2020.

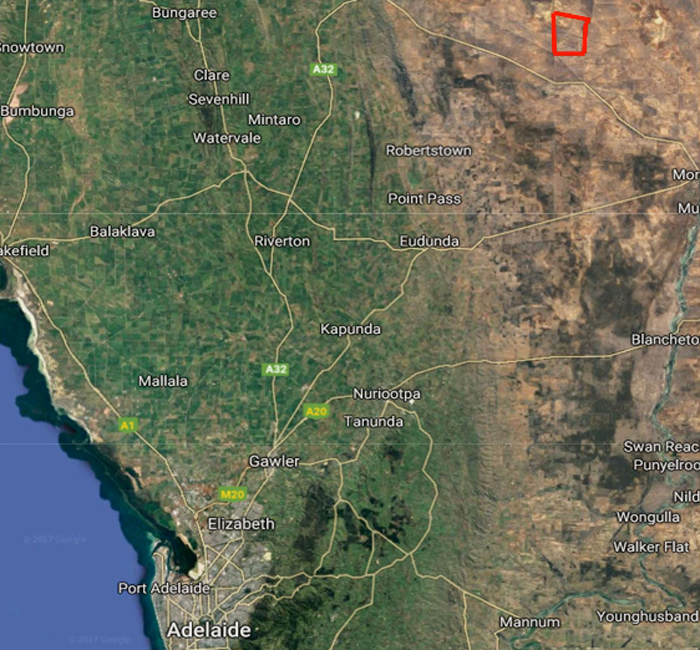

Solar River secured the land, about 150km north of the South Australian capital Adelaide, and received final development approval this month.

The Stage 1 array with single axis tracking will measure 3200 metres x 1800 metres and will be connected to the national grid by a transmission line to a substation near Robertstown, about 30km to the southwest.

The project is not reliant on grants or government support and will be 100 per cent privately funded through a mix of local and international investment.

Solar River Managing Director Jason May said the first generation from the site was expected in September 2019.

He said some of the energy produced would be contracted and some sent to the market for purchase by the retailers.

“Obviously there’s a fair bit to do in Stage 1 – there’s transmission lines and buildings to be constructed but the intention is to have everything finished by Christmas next year and then the main contractor will remain on site to continue with Stage 2,” May said.

“Really we just needed final approval and now the gun has been fired as it were so we’re making preparations to mobilise the main contractor and they’ll start advertising for jobs later this year.”

The solar farm will use a “cookie cutter” approach where sections with 5MW of PV are connected to a 5MW inverter that feeds in to a central inverter.

“They are all daisy-chained together by high-voltage cable and connected to the transmission network,” May said.

“The configuration of batteries and storage and photovoltaics to firm up electricity supply effectively acts like a baseload generator so it’s a little bit unique in that regard and we see it as the way forward for the industry.”

The Solar River project is proposed to be built about 30km northeast of Robertstown in South Australia.

May said the main purpose of the project’s grid stabilisation storage system and battery were to address intermittency issues sometimes faced by renewables.

“We can use the battery for those spot trading events when the price goes very high but our preference is to utilise it on a contracted basis to firm up our output to our longer term customers,” he said.

“The days are quickly disappearing where batteries are being used for those opportunistic revenues – their real place in the industry is to firm up renewables and the investors acknowledge that as well.”

The project, on a 5300ha piece of Australian Crown Land, is expected to create 350 regional jobs in the two-year construction period and 45 ongoing jobs for the 25-year life of the project.

South Australia leads the nation in the uptake of wind energy and rooftop solar with renewable sources accounting for more than 40 per cent of the electricity generated in the state.

However, the closure of two coal-fired power stations in recent years has increased the state’s reliance on energy supplies from the eastern Australian states, particularly in times of peak demand.

South Australia is also home to several globally significant renewable energy projects including Tesla’s “world’s biggest battery”, which was commissioned at Neoen’s Hornsdale Wind Farm in the state’s Mid North last year, and SolarReserve’s proposed 150MW solar thermal plant Aurora.

The Solar River site is less than 50km west of the proposed Lyon Group solar farm, Riverland Solar Storage, which is set to have 240MW of generation and 400MWh of storage.

Both sites are north of Goyder’s line, which separates what is considered land suitable for agriculture from the more hostile, arid outback.

May said the land just north of Goyder’s line was ideal for solar production because it was affordable yet still relatively close to the energy grid.

“South Australia is very rich in wind and solar resources – we have an enormous amount of it and it’s a free fuel if we choose to utilise it,” he said.

“We’ve got the technology to utilise it so let’s produce cheap electricity and sell it everyone who is connected to the network, which is the entire eastern seaboard.”

This article was originally published on The Lead South Australia. Reproduced here with permission. To read the original version, click here.