The UK capacity market has cost consumers billions of dollars since it was launched four years ago, but such subsidies – by our lights – may no longer be needed.

The market mechanism in question rewards power producers simply to be available to supply electricity. Bidders are paid regardless of whether they ever generate any electricity.

It allows utilities and other generators to commit to keeping coal, gas, nuclear and hydropower plants open for contract terms of either one or four years into the future.

Critics of the arrangement have noted that it rewards companies to keep their plants open even if they had intended all along to do just that anyway.

It isn’t too late to dial back the scheme and instead focus on supporting emerging modern technologies such as battery storage, as IEEFA recommended last year.

When the capacity rules were introduced in 2013, generators and utilities were painting a bleak picture of the UK’s future electricity market.

SSE, one of the so-called Big Six UK energy companies, warned at the time that the country was in a “critical period” that included the risk of blackouts.

Centrica, another UK energy major, went so far as to say blackouts could occur by 2017 and ran a campaign saying it would not build another gas power plant without a capacity market in place.

Fast forward four years and it’s clear that those warnings were over the top. While gargantuan sums have been paid out in capacity subsidies to existing generators, no new large power plants have been built – as was implied would happen.

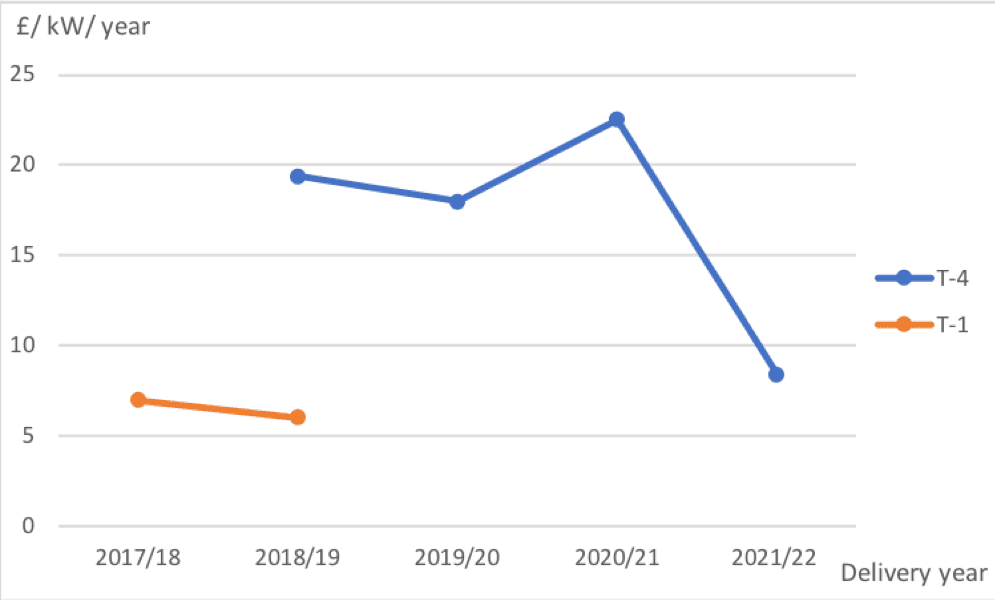

Further, prices declined in the latest capacity auctions, called T-1 and T-4 for contracts going one year and four years into the future (see the chart below), an indication that adequate power supplies aren’t really an issue.

One would expect rising prices if the electricity system was short on capacity and needed new generation.

One can find various explanations for falling prices: support in the program’s early years that led to the construction of a wave of very small generators; the prospective build-out of sub-sea interconnection into Europe; rising running times of gas power plants as coal power units have shut down; and reforms to the UK cash-out markets that reward power plants that can respond quickly to supply shortfalls and that penalize those that fail to perform as promised.

Growing evidence that capacity markets aren’t needed.

Beyond this, there is growing evidence that capacity markets, pitched by proponents as a necessary means of balancing rising amounts of variable generation, simply aren’t needed.

A report we published last week details many successful examples of markets around the world that have managed to integrate high levels of variable wind and solar power into their electric grids without resorting to capacity markets.

The study—“Here and Now—Nine Electricity Markets Leading the Transition to Wind and Solar” – shows major grid reliance on wind and solar ranging from 14-53 percent of total generation. Only one of the nine markets, Spain, has a comprehensive capacity market.

It turns out that countries with far higher levels of so-called variable renewables are doing without capacity markets, finding other measures (investing in transmission capacity, reforming power markets and requiring renewable energy technologies to play a bigger role in meeting power demand) to be sufficient.

Perhaps it is time for the UK to follow some of the examples occurring in these markets.

Gerard Wynn is a London-based IEEFA energy finance consultant.