The electoral turmoil within the world’s second highest emitter of greenhouse gases (number one for oil and gas, by a decent margin) is going to last a few weeks even after a winner is declared, so it’s worth taking a moment to pause and thinking about how Australia’s climate future is closely interlinked with the fate of the United States. For the most part, this centres around one of the trifecta fossil fuels driving dangerous climate change: gas.

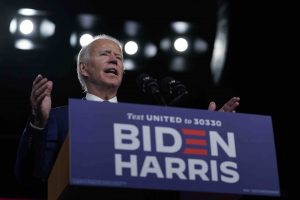

Gas recently overtook coal in terms of absolute emissions within the US. Either seeking to expand or seeking to transition the oil and gas industries in that country have been a major differentiator for the two candidates in the 2020 presidential election. Hours ago, the US exited the Paris climate agreement. The shifts are constant and they’re going to keep on coming last this year and well into the next, as the country is buffeted by political and economic change.

The US is inarguably a big player in climate geopolitics, but a collection of even-bigger players have together recently announced major shifts in their climate ambitions. China, South Korea and Japan have all announced net zero targets, joining a global coalition of countries that are declaring a form of climate action independence from the US. If Trump wins the election (less likely at the time of writing, but still a decent possibility), he will be fighting against a global tide of decarbonisation that is rapidly gaining momentum.

The French government has already put imports of US gas ‘on ice’, as reported by the Rocky Mountain Institute. “The delay was driven in large part by concerns over the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of US gas production, particularly from the Permian Basin”, writes RMI, highlighting the fact that Trump’s wildly anti-regulation agenda over the past few years may have locked in permanent sabotage for the country’s gas export industry.

The over-arching trend across the geopolitical climate landscape is bad news for Australia’s various fossil fuel industries, no matter the outcome of the US quasi-election. As coal burning begins to enter a similar structural decline to those seen in the US, the UK and Germany, those companies extracting and selling gas in Australia are scrambling to figure out how to maximise their snaffling up of the gap left by coal’s absence, in the coming decades.

When it comes to power, the heart of this trick lies in intentionally muddying the difference between supplying large amounts of energy, and supplying a ‘backup’ grid stability role. Both Australia’s major parties have partaken in this conflation in recent months, among this rising intensity of geopolitical climate drama. “According to reports, Fitzgibbon has now succeeded in forcing the Labor Party to openly support the construction of new gas production facilities and even new gas generators”, wrote RenewEconomy’s Michael Mazengarb.

https://twitter.com/KetanJ0/status/1322991204494045185

There are two possible future for gas in Australia’s power system. The first I explored in a recent ‘graph of the day‘, showing what the Australian Energy Market Operator has modelled for an optimised Australian gas system. The results are relatively simple: you don’t need a lot of gas output to run the grid on mostly renewable energy.

Notably, in this system, gas capacity is a far higher proportion of the grid than gas generation. This is a very important distinction: how much energy is the deciding factor for the emissions of a thermal power station, not how much capacity. Let’s look at the various gas generation and capacity levels in 2042, in AEMO’s scenarios:

What AEMO’s models tell us is that the NEM can absorb an enormous quantity of renewable energy, with the majority of balancing and integration coming from new interconnectors, storage of various ‘depths’ (hydro, batteries) and responsive demand. In every scenario, the proportion of actual generation from gas remains a small fraction of total, with the technology only coming online in the rarest of instances, when all those other options have been exhausted.

The alternative – the presumed future being argued for by advocates of fossil fuels like Joel Fitzgibbon and Scott Morrison – is a grid in which renewable output is crowded out by a massive expansion of ‘baseload’ style gas-fired generation. In fact, it is America’s grid that is the model for this alternative scenario:

This is the exact mechanic through which the ‘transition fuel’ argument morphs into a ‘climate damage’ situation. The justification for a tiny smattering of rare gas-fired generation as ‘back up’ is weak, but barely acceptable (as batteries and demand response get cheaper, even this argument will collapse). But a very significant expansion of gas-fired power on Australia’s grid would cut into the growth of renewables, stifling emissions reductions significantly. Already, Australia has added twice as much gas as coal has been removed, resulting in a final emissions reductions value of zero:

https://twitter.com/KetanJ0/status/1323609058708987904

Both major parties will now have to face down exactly the same conundrum: where does gas belong, in a future energy system? So far, both have done an extremely poor job at presenting the problem as one with a climate cost that increases as the dial is moved towards the American ‘baseload gas’ model. Gas is also used heavily in buildings and in industry, and a separate and likely more contentious fight between electrifying these sectors or replacing fossil gas with lower or zero carbon options (the slower option more favoured by the gas industry) looms large. In parallel, Australia’s domestic emissions are inextricably linked to the magnitude of gas exports, because extracting that substance from the ground is incredibly emissions intensive.

The future of clean energy in Australia is not set. Massive geopolitical shifts are playing into the pathway for future development in Australia, and it is worth paying close attention to these dynamics. The next election will be a significant test of the question at the heart of gas, in Australia: do we treat it like a fossil fuel? If that can be managed, there is hope for a significantly expanded role for clean energy, alongside cleaner air and better climate outcomes for the whole world.