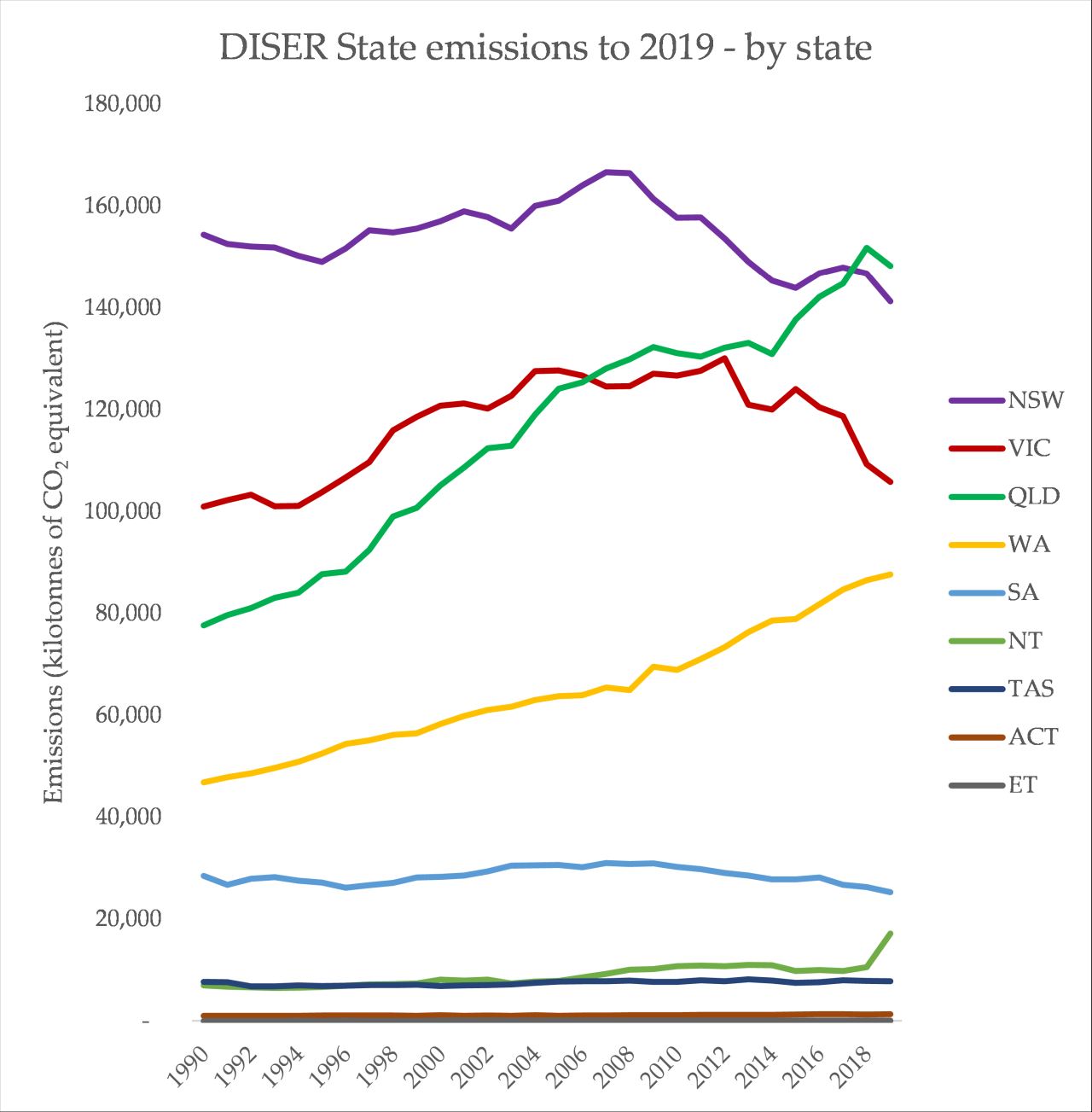

The state of New South Wales is currently sitting alongside Victoria as the two states of the ‘big four’ that are actually reducing emissions in a clear, sustained and absolute sense. Though both lean heavily on the land use sector for these falling numbers, a growing role of renewable energy and a notable drop in mining activity (which produces emissions domestically) have played at least some role in both.

What is startlingly clear is that none of this is sufficient for any state to really be on track to net zero by 2050. Though it will differ across regions, a rough rule we can focus on is that grids should be mostly (95 to 100%) decarbonised by at least 2035, and preferably by the end of the current decade. As I’ve written prior, that baseline is essentially missing from action in most of the debate on electricity, energy and climate in Australia.

Here’s the most recent example: a new fossil gas power station has been announced, in New South Wales. EnergyAustralia is building a 300 megawatt ‘fast start’ gas generator with hefty grants from the state ($78m) and federal ($5m) governments. It’s there purportedly to replace the capacity lost when one of NSW’s biggest coal plants, the Liddell power station, shuts down. The Tallawarra B power station will open sometime around 2023.

We don’t need fossil fuelled power stations to replace other fossil fuelled power stations. “The costs of energy storage have declined rapidly in recent years, and it’s now clear that it provides a lower-cost solution for firming low-cost solar and wind energy resources,” Clean Energy Council CEO Kane Thornton said, of the decision. That is before you account for the implicit subsidy gas-fired power receives in offloading the costs of greenhouse gas emissions and fuel extraction onto society, and of course, the explicit subsidies this facility is receiving.

A state recently congratulated for its vision and ambition on climate is now directing taxpayer funds towards avoidable fossil projects. It isn’t the worst fossil project – it’s smaller than most and won’t operate much. But it represents a broader and worrying trend, and it’s worth digging into why this isn’t something to be welcomed.

The carbon footprint of Tallawarra B

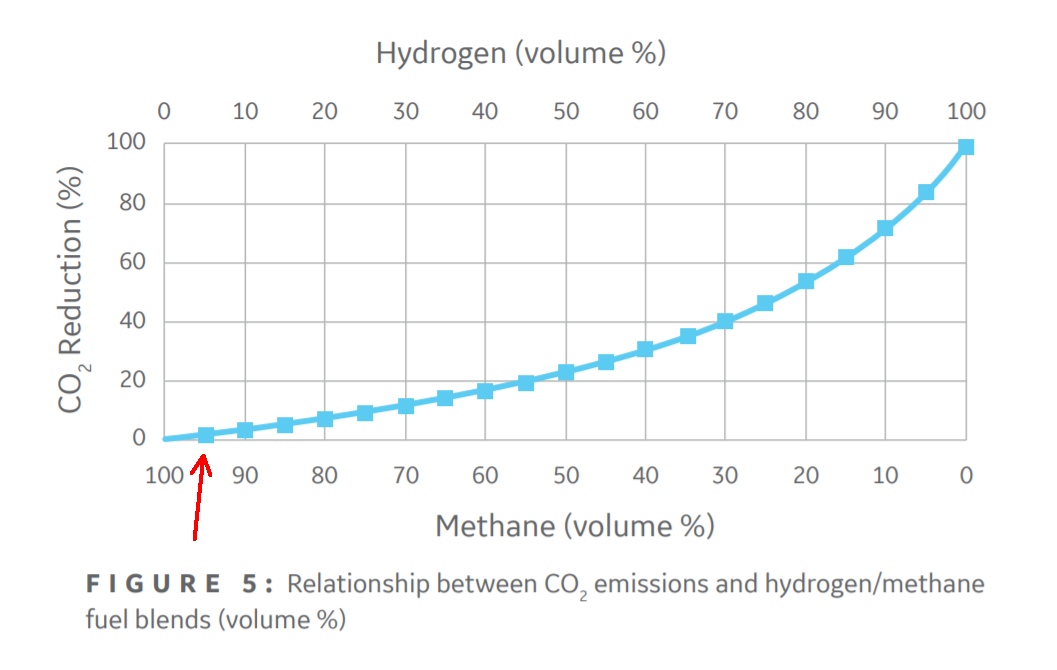

The plant will run on 100% fossil gas for its first two years of operation. After 2025, it will be 95% fossil gas and 5% “green hydrogen” (the NSW government press release defines that as “cheap, reliable type of energy that is made using 100% renewable sources”). The turbine manufacturer, GE, provides a handy visualisation of what type of CO2 reductions a 5% blend entails, in a recent white paper – I’ve added an arrow to mark out the 95% methane mix by volume, in the graphic:

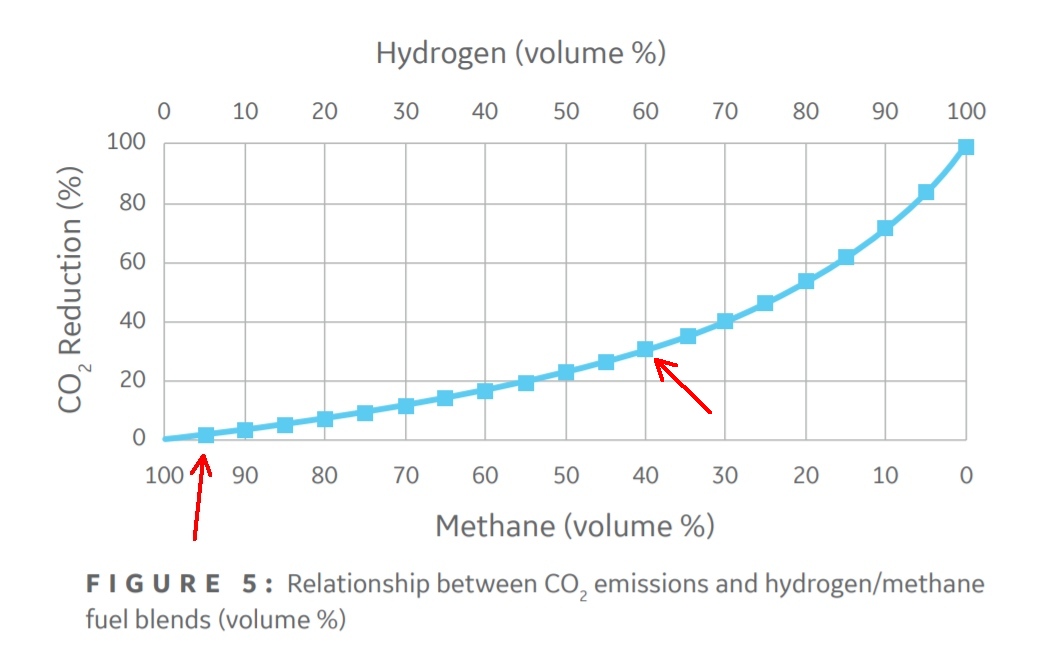

The Daily Telegraph reports, in a glowing article, that “share that will eventually rise to 60 per cent”. Of course, there’s no date on that.

The Daily Telegraph reports, in a glowing article, that “share that will eventually rise to 60 per cent”. Of course, there’s no date on that.

But GE’s white paper highlights something extremely important: you don’t get a 50% reduction in emissions by blending methane and hydrogen equally.

As GE explains, this is because methane and hydrogen have very different energy densities. That means you have to cram in a lot of hydrogen just to get a bit of an emissions reduction. So a 60% hydrogen / 40% methane blend only gets you around a 35% cut in emissions. To cut emissions by 50%, you’d need at least 75% hydrogen in the mix! So these proportions are extremely misleading.

The most recent modification submitted to the NSW government, in 2020, shows that it would produce 1,177,804 megawatt hours of energy in a year, around 588.49 kilotonnes of CO2-e, around a 0.5% increase in NSW total emissions. This doesn’t include any ambitions for blending hydrogen. The core reason this is so low is because the plant is expected to generate infrequently, as it’ll be a ‘peaker’ called on in rare circumstances of high demand and low wind and solar output. Though ‘open cycle’ gas turbines have a higher emissions intensity than the ‘baseload’ closed cycle turbines, they generate far less, and subsequently have lower absolute emissions.

The most recent modification submitted to the NSW government, in 2020, shows that it would produce 1,177,804 megawatt hours of energy in a year, around 588.49 kilotonnes of CO2-e, around a 0.5% increase in NSW total emissions. This doesn’t include any ambitions for blending hydrogen. The core reason this is so low is because the plant is expected to generate infrequently, as it’ll be a ‘peaker’ called on in rare circumstances of high demand and low wind and solar output. Though ‘open cycle’ gas turbines have a higher emissions intensity than the ‘baseload’ closed cycle turbines, they generate far less, and subsequently have lower absolute emissions.

But that means the inclusion of hydrogen is essentially meaningless. With a 5% blend of hydrogen, that’ll be only around a 2-3% reduction in total annual emissions. With a 60% blend of hydrogen, it’ll only be around a 25% cut. If we very generously assume that this plant will be 60% zero emissions hydrogen by 2035, this is what the cumulative emissions profile looks like, compared to a pure gas plant:

Despite the clear presence of carbon emissions no matter how you cut the data, this plant was described in the Financial Review as a “carbon neutral” gas plant, and in the ABC as a “net zero” hybrid power station. Despite only around 15% of plant emissions being cut through hydrogen blending pre-2050, the remaining 85% is named “residual” emissions. That’s some residue.

This weird language stems from EnergyAustralia’s promise to “offset” the emissions. This rhymes with the suggestion of a recent report from the Grattan Institute to build a range of new fossil-fuelled power stations to provide “backup” for the grid, and purchase carbon offsets for their emissions, instead of building zero emissions grid balancing technologies. Grattan themselves highlight the significant problems with using offsets to justify worsening avoidable emissions, but now we see a real-life instance of decisions being made precisely on these grounds.

While the controversial nature of carbon offsets has been known for years, yesterday a major new investigation from Greenpeace’s Unearthed and the Guardian revealed that schemes using ‘avoided deforestation’ to claim emissions reductions are largely fabricated.

Carbon offsets used by major airlines based on flawed system, warn experts. "Difficult to judge if the emission reductions claimed by projects were real."https://t.co/QO9IRxyiB4 Story by @pgreenfielduk and @UE, @Greenpeace

— jonathanwatts (@jonathanwatts) May 4, 2021

A lot of gas and nothing in return

While the emissions footprint of this plant is relatively small with and without hydrogen (compare the annual 588 ktCO2-e to Liddell’s monstrous 14,700), this new plant is part of a bigger problem that is driving a trajectory to badly miss ambitious climate targets.

One justification frequently thrown around for gas peakers is that they enable a greater quantity of wind and solar to be integrated into grids, leading to a comfortable net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Putting aside zero emissions alternatives that enable the same effect, it is utterly irrelevant in the context of the unfurling project to keep coal-fired power stations open as long as possible, using government intervention and aggressive pro-fossil policy.

In fact, today, the Australian has a piece featuring the new boss of AGL energy Graeme Hunt, in which he very clearly insists that their NSW plant, Bayswater, and their Victorian plant, Loy Yang A, will be “amongst the last if not the last to close” in Australia. Queensland’s state-owned coal company won’t be closing its operations any time soon, and the government jettisoned an entire CEO for daring to verbalise that possibility.

A terrifying game of chicken has emerged, where each coal plant operator is hanging on, hoping to soak up the hit in wholesale price rises when another coal plant falls. The absence of any clear state or federal coal phase-out plans has become a perverse incentive to prolong emissions as much as possible. There is an army of powerful people working against economic factors – domestic and global – that are making early closures more likely, and they are relatively likely to succeed. So what exactly is the justification for building new gas plants, again?

Without a clear program to close coal in line with ambitious climate targets, new gas plants will simply pile on top of high, prolonged coal plant emissions, creating a worse outcome than one in which we use only zero emissions grid firming options.

The principle is the problem, here. A new fossil fuelled power station is being funded by significant taxpayer grants. It will doubtless be pointed at to justify further gas mining projects, and gas pipeline projects. The federal government’s own pet project – the Kurri Kurri gas plant – will probably go ahead too, despite neither being needed to replace Liddell. It will release greenhouse gas emissions, and offsets and hydrogen will be used as window-dressing to justify that climate damage. And it won’t contribute to the early closure of any coal-fired power stations, because the owners of those plants are now aggressively fighting to ensure those plants also receive government money to stay open for as long as they possible can.

NSW, and Australia, remain badly off track to achieve ambitious climate goals because these micro-level decisions add up to a macro-level phenomenon: a refusal to consider emissions as damaging or harmful, at least not in any urgent sense. The hydrogen veil on this announcement covers up a deep, systemic and worsening problem for Australia’s grids.