There’s little doubt that a successful clean energy revolution is going to require the construction of a large quantity of new technologies to replace defunct coal, gas and oil powered machines. Wind turbines, solar panels, electric cars, buses, trains, bikes, heavy and light industry and a vast network of supporting infrastructure such as transmission lines and batteries will all be required, even in scenarios that involve significant reductions in electricity demand.

One of the core reasons for a transition away from fossil fuels is that climate change is itself a threat to human rights. Access to clean water, safe living, power, stable democratic societies – these are all under major threat from the actions of the fossil fuel industry. And that industry has a track record on humans rights that is eye-wateringly bad, even before we take into account the impacts of greenhouse gases.

What is utterly unavoidable is that this new energy world must be built wholly within the confines of the old one – the track is being laid while the train is moving. And that means the risks of the problems of the old system flowing directly into the new system are very high. The machines of the new world must be built from something; and some of those things will be extracted from the ground and processed in unfair, damaging ways. Reducing this as much as possible during this sensitive moment of change is extremely vital – without it, it threatens to derail the entire project at a time when the alternatives – a perpetually fossil-fuelled world – are unthinkable.

The Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC) has been tracking the nature of this problem for some years now. In 2020, they released a clear benchmark for the world’s various renewable energy companies to focus on what good humans rights look like for the renewable energy industry. “Low scores in high risk areas for the industry, like land rights and respect for the rights of indigenous peoples, are deeply concerning”, wrote former President of Ireland Mary Robinson in the introduction. The report focuses on the biggest wind and solar companies, both manufacturers, project managers and investors and owners.

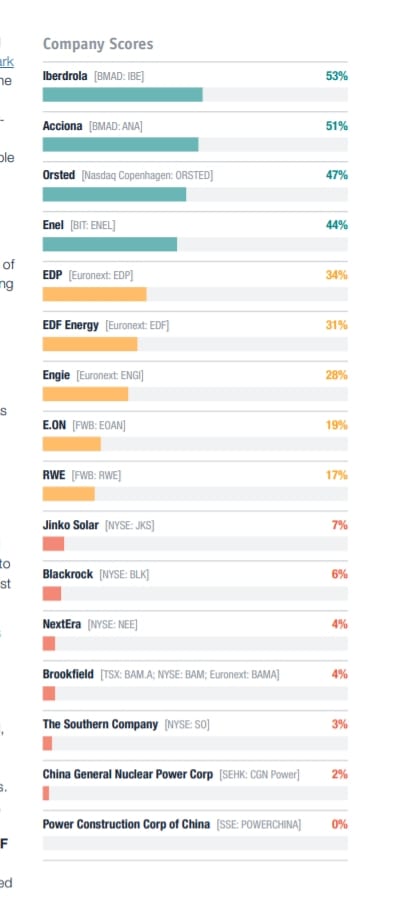

Some of the documented instances of human rights violations that occur in the supply chains of these companies are eye-opening, and range from killings and threats through to land grabs, dangerous working conditions and harm to Indigenous people’s lives and livelihoods. Most occur in Latin America (61% globally), with European companies scoring higher and Chinese and American companies scoring lower:

Earlier this year, BHRRC launched their transition minerals tracker, highlighting issues around the extraction of the raw materials required to build the new machines of the energy system. The human rights impacts in this ‘earlier’ part of the supply chain are wider ranging, and arguably more severe. Some companies, even those with human rights policies, create health dangers, impinge on Indigenous rights, restrict access to water, deny freedom of expression and, in the worst cases, engage in violence to tamp down protest against mining operations. “By introducing measures to end these harms now, we can secure a future not only where a net zero carbon economy is achieved but where all peoples benefit from a sector that is rights respecting and sustainable”, say the authors of the report.

Earlier this year, BHRRC launched their transition minerals tracker, highlighting issues around the extraction of the raw materials required to build the new machines of the energy system. The human rights impacts in this ‘earlier’ part of the supply chain are wider ranging, and arguably more severe. Some companies, even those with human rights policies, create health dangers, impinge on Indigenous rights, restrict access to water, deny freedom of expression and, in the worst cases, engage in violence to tamp down protest against mining operations. “By introducing measures to end these harms now, we can secure a future not only where a net zero carbon economy is achieved but where all peoples benefit from a sector that is rights respecting and sustainable”, say the authors of the report.

Jessie Cato is the Programme Manager, Natural Resources and Human Rights at the BHRRC and spoke to RenewEconomy about the work of the group in tracking these rising issues around the supply chain for clean energy. “We are seeing an increase around these minerals as production and exploration both ramp up,” she says, highlighting increasing demand due to growth in clean energy and electric vehicle technologies. But the opportunities for both mining companies and clean energy companies to take strong action to address these problems are rich.

“Companies that work in renewable energy, are often interested in this topic because they have a social mission and because they want to do good,” she says. “There is a growing acknowledgement that the complexity of supply chains plays a huge role in allowing human rights abuses to continue, and in remedying the situation, mapping those supply chains. There’s more coverage now looking at critical bottleneck minerals such as cobalt or lithium, but as mentioned the array of minerals needed to produce RE technologies is much broader. It can be daunting to companies, but its absolutely necessary in stamping out these violations”.

“If green energy is to be clean energy, it must learn from the mistakes of the past, and move forward in a rights respecting way.”

Find out more & explore the tracker 👉 https://t.co/00LC04Kqfd pic.twitter.com/9talN6fV6G

— Business & Human Rights (@BHRRC) February 3, 2021

Part of the problem underpinning these concerns is far later in the process, during construction and operation. However, many companies are taking new approaches to fairer models of operation. “Co-ownership and/or benefit structures have been increasing in Renewable Energy projects, most notably in communities in Canada and New Zealand, and we see this is a model that more companies should look, to truly work in partnership with communities and to provide a sustainable transition where the benefits, be that fiscal or energy access, are properly shared, and the salient risks in this sector can be more comprehensively addressed”.

In some ways, Australia has the potential to be a leader in addressing these issues while they’re still relatively contained. Recently, Independent MP Helen Haines has spearheaded an effort to formalise the creation of a ‘Local Power Agency’, alongside a variety of existing, innovative community power projects.

Often, the externalities of the process of creating, building and running renewable energy technology are weaponised to justify the continued dominance of a fossil-fuelled world. While this is done in bad faith, if it leads to the element of truth being ignored rather than addressed, then those attacks are successful in an indirect way. The goal, of course, is a clean, healthy, fair world in which human life can flourish. There’s no way a fossil fuelled world could ever be compatible with that – with some directed efforts, a clean energy powered world could get pretty damn close.