The Australian Greens have now launched details of how they would meet their long held policy proposal to take Australia to 90 per cent renewable energy for its electricity needs by 2030.

The first thing that should be noted is that it is not going to happen. And that’s not because the technology doesn’t exist to effect the transition, it does: The Australian Energy Market Operator assured us of that in a detailed analysis completed in 2014, and said it may not be any more costly than business as usual.

The reason it won’t happen is that the Greens would not get into power fast enough to effect that change. Even a power sharing arrangement with Labor couldn’t achieve its policy goals, because Labor – despite its proposed 50 per cent renewable energy target by 2030 – remains too wedded to the fossil fuel industry.

The Coalition, meanwhile, has said that 23.5 per cent renewable energy is more than enough, and nothing said since Malcolm Turnbull became prime minister suggests anything much is going to change quickly. The ongoing capital strike by the private sector players is indicative enough of that.

The other reasons are a mixture of ideology and vested interests. Witness the headlines and commentary that will surely appear in the mainstream press, and which has accompanied Germany’s Energiewende (energy transition), and the impending closure of the last coal fired generator in South Australia.

Powerful interests, in the fossil fuel and the pro-nuclear sectors are launching a scare campaign against wind and solar that rivals the campaign launched by the fossil fuel industry against climate science.

But let’s have a look at the 90 per cent target that Greens leader Richard di Natale is proposing. As he agrees, it is ambitious, “but ambition is what required”, both to meet climate targets and to ensure that Australia remains competitive in a largely decarbonised society.

Indeed, the Paris climate talks – beginning next week – are poised to reach agreement on a target that will essentially decarbonise the world’s electricity system by 2050. Australia, with its huge wind and solar resources, is better place than nearly any other country to adopt those technologies.

And if the Paris talks do result in agreement – and a long term target that could include net zero emissions, or “carbon neutrality” by 2030, or even keeping an option for a 1.5C target that Australia suggests it is prepared to sign up to – then the world is going to have to get moving pretty quickly.

The Greens are merely making the point that if the world wants to meet these targets, then it needs to move to net-zero carbon pollution by 2040.

The 2C target will require the world to do more or less the same by 2050 in any case. The difference between the Greens and the mainstream parties is that they have actually mapped out a plan to get us there. For the others, there is a disconnect between rhetoric and policy.

The International Renewable Energy Agency, in a report to be released this week, says renewables and efficiency can account for most of the reductions. It has previously said that Australia should be aiming for than 50 per cent renewables by 2030.

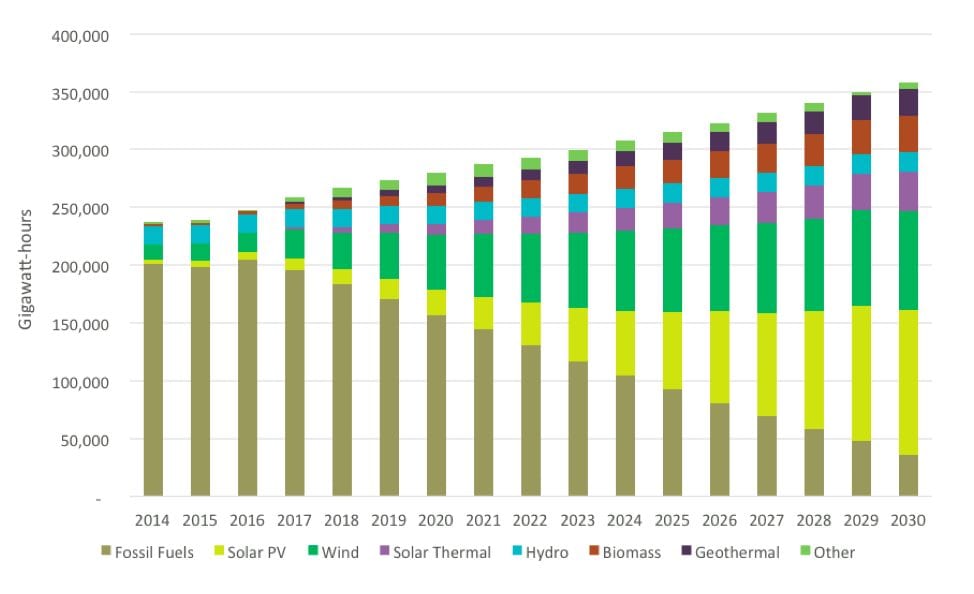

So, for the details of the Greens policy. First of all, here is what the Greens say that 90 per cent renewable energy generation might look like in 2030 – although they point out that technology shares could change depending on their cost curves in coming years.

The Greens note that wind energy will play the major role in the next few years, before solar PV, and to a lesser extent solar thermal become the dominance new technology. Energy storage, while not specifically separated out in this generation forecast, will play a significant role in managing the network and matching dispatch times.

The Greens have proposed two possible policy scenarios that could deliver this target, which is based on the assumption that widespread adoption of electric vehicles and electrification of manufacturing production (rather than using liquid fuels), will increase demand to 358TWh, more than 50 per cent above some scenarios, and a similar amount above current levels.

The first scenario envisages a series of reverse auctions administered by a new body, called RenewAustralia, in a similar fashion to those pioneered by the ACT government in its own program to reach 90 per cent renewable energy by 2020.

This would deliver about 100,000 GWh of new clean energy generation capability by 2030. This would be supplemented by what could be the most controversial element of their proposal, the use of public funds for publicly-owned generation assets (a total of 129GWh).

In this scenario, the large-scale renewable energy target would be expanded and extended to 52,500 GWh of electricity generation by 2030; and the small scale target would be continued to provide 25,800 GWh of small-scale renewable energy gene ratio, mostly rooftop solar.

A second scenario anticipates much higher uptake of rooftop solar – both residential and commercial (39,000GWh) – but is in line with the uptake envisaged by AEMO is some of its recent network planning. This scenario envisages less capacity delivered by public finance, but more capacity from reverse auctions.

These mechanisms would be combined with wider market trends towards greater energy efficiency, and household storage.

It would also be accompanied by legislation that would place strict pollution limits on coal fired power generators, of the sort that have been imposed in the US and China (remembering that Australia has some of the dirtiest coal fired generation in the world).

This is not likely to please the incumbent utilities. AGL Energy, for intance, has proposed no new coal fired generation but wants to keep plants such as Loy Yang A – Australia’s biggest polluter – open until 2048. The Greens would have that facility closed in little more than a decade.

Hazelwood, one of the oldest and dirtiest plants, would be closed in 2017. The black coal generators in NSW would be closed between 2024 and 2029, and the Queensland coal plants between 2020 and 2030.

“There is no escaping our economic future. It is clean and green or it is no future at all,” the Greens document says.