One of the pet grievances of the renewable skeptics and the anti wind and solar brigade is that nearly all claims of 100 per cent renewables are not really that at all.

They argue that if an industrial precinct, mine, company, town, territory or state was really 100 per cent renewable, then ever single electron of demand would be met by wind or solar, or hydro.

The reality is that it’s not. Most 100 per cent renewable claims are based on buying an equivalent amount of supply from wind and solar that equates to the total amount of demand over a year, if not the timing.

The reason is that there really is no point – the grid exists and it acts like a giant battery, and trying to be holier than thou by abstemiously sourcing every electron from renewables would add unnecessary costs. That day will come, however, as I will discuss below.

But corporate demand is starting to shift. The big corporate are now looking increasingly at matching the supply offerings of wind, solar and storage to their demand profiles.

The reason that this can be done is that the addition of storage makes it easier, and there is growing scrutiny about the integrity of the 100 per cent renewable claims. But the biggest reason of all is cost – there is absolutely no doubt that when wind, solar and storage costs are abundant, the price is lower.

Energy users want to get rid of those moments when wind, solar and storage are not matching supply and when prices jump. They are asking the renewable providers to assume that risk, and that is creating some interesting, and exciting new challenges for the developers.

Perhaps the most interesting contract announced in recent times is the for the 24/7 “baseload renewable” energy supply deal between French developer Neoen and BHP’s giant Olympic Dam mine, one of the biggest copper deposits in the world and one of the biggest underground mines.

The contract is for an uninterrupted supply of 70MW around the clock – around half of the mine’s average demand – and it will ostensibly be met by two new projects.

One of them is 412MW first wind energy stage of Neoen’s giant Goyder South complex in South Australia, of which around one half will be “dedicated” to the BHP contract. And the other is the 200MW two hour (400MWh) Blyth battery in the same state that will fill in the gaps.

But Neoen made it clear that while – in principal – the battery could fill in the gaps of the Goyder South wind output, that’s not the way it will be deployed.

Jean-Christophe Cheylus, Neoen’s head of energy, explained how the company is approaching it during Neoen’s strategy update last week.

“In the past few years, we met many customers who wanted to have green energy that were not satisfied with the traditional, generation following PPA,” Cheylus says. “They felt there was simply not enough adequacy between what they were buying and what they were consuming.

“In order to bridge that gap, we combine wind generation storage optimisation and market capabilities to structure a whole new world baseload PPA.

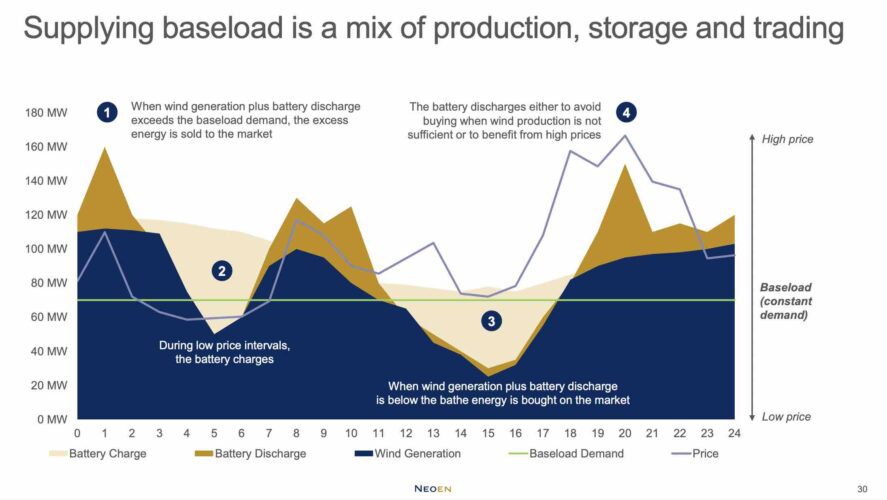

“This is how (the BHP contract) works. The baseload is a constant demand, we must provide all the time whatever the wind generation. But we do not use the battery to store excess wind generation and restitute it later, we use the market instead.

“So, when when generation and battery discharge exceeds the base load demand, the excess energy is sold to the market. And when the wind generation plus battery discharge is below the baseload demand, the missing energy is bought on the market, this institution free.

“Now, when prices are low, the battery will charge and when prices are high, the battery will discharge.”

Cheylus went on to explain the company could make more money buying at low points and selling at high points, rather than keeping the battery purely as the wind energy’s backstop.

“In this strategy, we generate more power than we sell as we do when we contract a traditional PPA. But in addition, we deliver high value product to our customer and we leverage our battery capacity to mitigate our merchant exposure, and we benefit from price volatility.”

Neoen is taking a similar approach with a “virtual battery” contract that is has signed with AGL. Ostensibly, the contract is for 70MW/140MWh capacity from the 100MW/200MWh Capital big battery that Neoen is building.

Cheylus describes the capability provided to AGL as similar to an app on a phone, and Neoen can still use the battery to deliver its obligations under the ACT contract that underpinned the facility.

Cheylus describes the battery agreement as “essentially a financial product – the customer can conceptually charge or discharge, review virtual energy reserve, and benefits from the financial outcome of its decisions.

“If I had to summarize in a few words, the essence of our energy management activity is that we are integrating our resources composed of our own renewable generation, our batteries and our access to energy markets in order to deliver new offers and services to our clients and to manage new instruction exposure.”

Of course, in some situations, customers and developers are going to have to go one better and deliver a true 100 per cent renewable outcome, or as near as dammit.

BHP will be facing this challenge with the planned $1 billion Musgrave West project that it will inherit as part of its agreed takeover of Oz Minerals.

The mine, located in a remote region near the WA/Northern Territory border far from any grid connection, aims to source at least 80 per cent of its power needs from onsite wind and solar and battery storage.

It could go even higher, depending on its ability to shift demand needs (processing plant etc), but the fact that it can go even this high seems remarkable enough – given that we are constantly told that wind and solar can’t power industries, and some still insist that the lights will go out if it accounts for more than half.

But as South Australia has already proven – 80 per cent average wind and solar over the December quarter, even with a relatively thin connection to the main grid, and 72 per cent in the week that it had no synchronous link – this is readily achievable.

And let’s not forget that the aim for the entire National Electricity Market – the main grid covering the eastern states and Tasmania – is for 82 per cent by 2030. That’s the shared ambition of the market operator, whose job it is to keep the lights on, and the federal government, which needs to keep consumers happy.