The Grong Grong solar farm powered up on Friday and is now operational, proof – the people behind the project say – that community-owned renewables projects can get off the ground.

The 1.5 megawatt (MW) project was officially launched a month ago, a celebration of a four year endeavour by Komo Energy to build the country’s first crowdfunded solar farm.

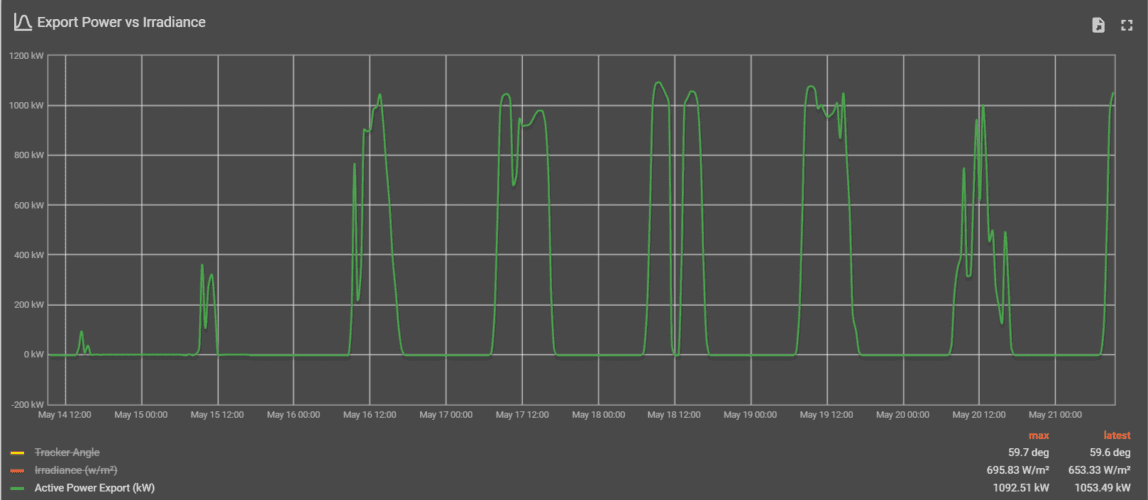

The farm is not quite generating at nameplate capacity due to wintery conditions in the Riverina, New South Wales (NSW) location, and is currently exporting a maximum 1.1 MW to the grid, says Komo Energy director Jonathan Prendergast.

“The project is battery-ready [for a 2.3 MWh storage system] and we’ll need to raise $1.3 million, but we have no timeline for that yet,” he says.

Full commissioning will take place after a second test in October.

Komo Energy started seeking wholesale Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) for Grong Grong and its other crowdfunded project, the 1.4MW Goulburn solar farm, in late 2022. The Goulburn project is expected to start construction later this year.

Komo Energy raised almost $2 million for the Grong Grong project through two seed rounds and two crowdfunding processes, while $735,000 was raised for the Haystacks Solar Garden. Grants also came from the NSW Government’s Regional Community Energy Fund.

The Haystacks Solar Garden, part of the Grong Grong project, is where some 333 cooperative members can purchase a 3kW solar “garden plot” and enjoy bill credits via energy retailer Energy Locals.

The project is targeting a return of 5-10 per cent for its investors.

Networks need to get act together

Late in 2023, network modelling company Neara found that some 10GW of capacity was unused on distribution networks — capacity that could be used by small and mid-sized renewables such as Grong Grong.

But unlocking this requires help from the networks, says Komo Energy director Gerald Arends.

“When we saw that we were delighted because we have argued for years that our midscale projects are really an opportunity to connect to the neglected distribution networks,” he told Renew Economy.

However, Komo Energy also learned that building projects at the smaller end of the market means using local contractors who don’t have direct experience commissioning renewables projects need help, and so do developers.

“When you want to promote regional jobs at the same time as regional renewable energy rollout, you ned to rely on regional contractors. They are typically smaller and often more generalist, and therefore need specific extra training in solar commissioning,” he says.

“[In terms of networks] we felt supported by Essential Energy [whose network covers 95 per cent of land area in NSW] but it still comes out of the public sector and they rarely actively offer a guide as to what they require.

“It would be desirable if Essential Energy and other networks took a more proactive approach with guidance, template commissioning plans, and key issues lists, so contractors who don’t work in this area all the time can use network operators’ unique experience.

“We would wish that Essential Energy is more proactive in the way it guides and marshalls the commissioning process.”

Community and shared ownership might be the future

Renewables projects that give their local communities more involvement than being mere recipients of developer largesses may become the new norm in Australia.

As renewable energy projects become more common, and as opposition campaigns ramp up, developers are seeking more ways to bring their new neighbours along on the journey.

This week, Engie announced that it was broadening the concept of “neighbour” from dwellings that are strictly adjacent, to those who might be affected by other elements of a project such as enduring higher traffic during construction or being able to see it.

And offering an element of shared ownership is not foreign in Australia: Squadron Energy is offering to some residents in the Central-West Orana Renewable Energy Zone (REZ) the opportunity to buy into the 414 MW Uungula and 700 MW Spicers Creek wind farms.

The five-turbine Coonooer Bridge wind farm in Victoria combined corporate and community ownership between developer Windlab and 30 landowners within 3km of the wind farm.

Two other small wind farms, Hepburn Wind in Victoria and Denmark in WA, were also built with a combined ownership structure, and OSMI, the developer of the contested Delburn wind farm in Gippsland, Victoria, says it will also offer community co-investment.

Indigenous groups have also been able to negotiate different ownership structures as a bloc such as the Sunshine Hydro project in Queensland or traditional owners of Yindjibarndi lands in Western Australia’s Pilbara region.