A new report from the Grattan Institute released today highlights something well known among energy wonks and fervently denied by the Australian government: you can quickly and simply slice out the vast majority of fossil fuels in a grid. Australia’s network of generators producing electrical power are a substantial chunk of the country’s emissions, and are inarguably step #1 for the process of the whole economy aligning with global climate goals.

For some time, the decarbonisation of the grid has been badly under-estimated. The Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) releases an annual projection of emissions, and that projection has been ratcheting downwards over the past half-decade due almost entirely to adjustments to the emissions of the electricity sector.

Only two short years ago, Australia’s government was campaigning in a federal election by aggressively opposing a 50%-by-2030 renewable energy target. A few months later, DISER predicted that to be the default pathway.

And it was also very recently that Australia’s Energy and Emissions Reduction Minister Angus Taylor claimed Australia had already passed a 25% ‘threshold’ for renewable energy.

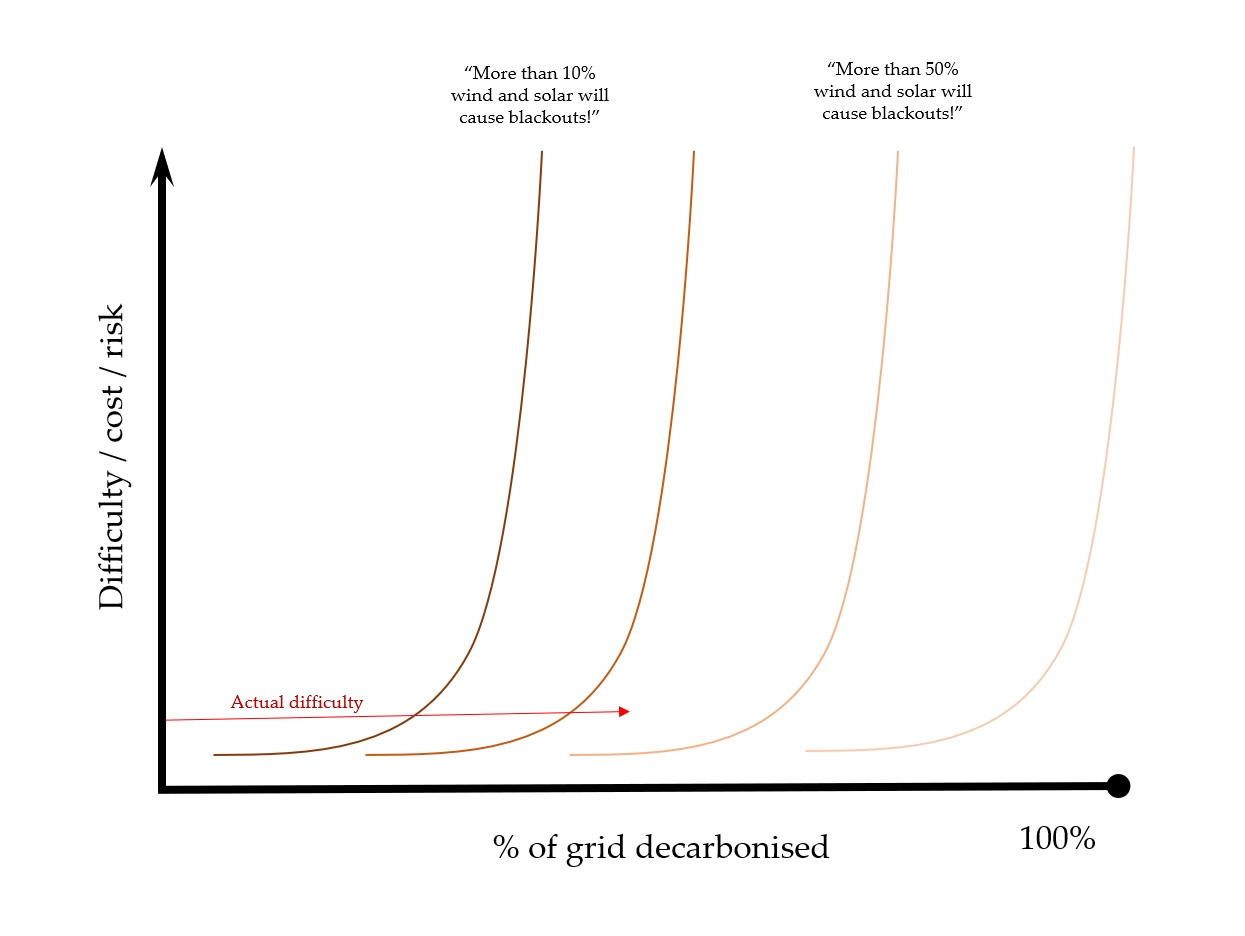

What is happening here is a shifting curve. When it comes to the difficulty of integrating renewable energy, the naysayers imagine that the difficulty is right around the corner, whereas the experts and the advocates both seem to align in saying that it’s far closer to the end point. This is a subjective representation of the numbers, but you get the idea:

The Grattan Institute report doesn’t fall prey to the ‘early difficulty’ scaremongering that many of Australia’s key political figures indulge in. They are in fact largely optimistic about reaching a 90% fossil-free grid, with literally zero coal, as long as there is some clearer political leadership, some good planning and some good decisions around regulation and technology.

The Grattan Institute report doesn’t fall prey to the ‘early difficulty’ scaremongering that many of Australia’s key political figures indulge in. They are in fact largely optimistic about reaching a 90% fossil-free grid, with literally zero coal, as long as there is some clearer political leadership, some good planning and some good decisions around regulation and technology.

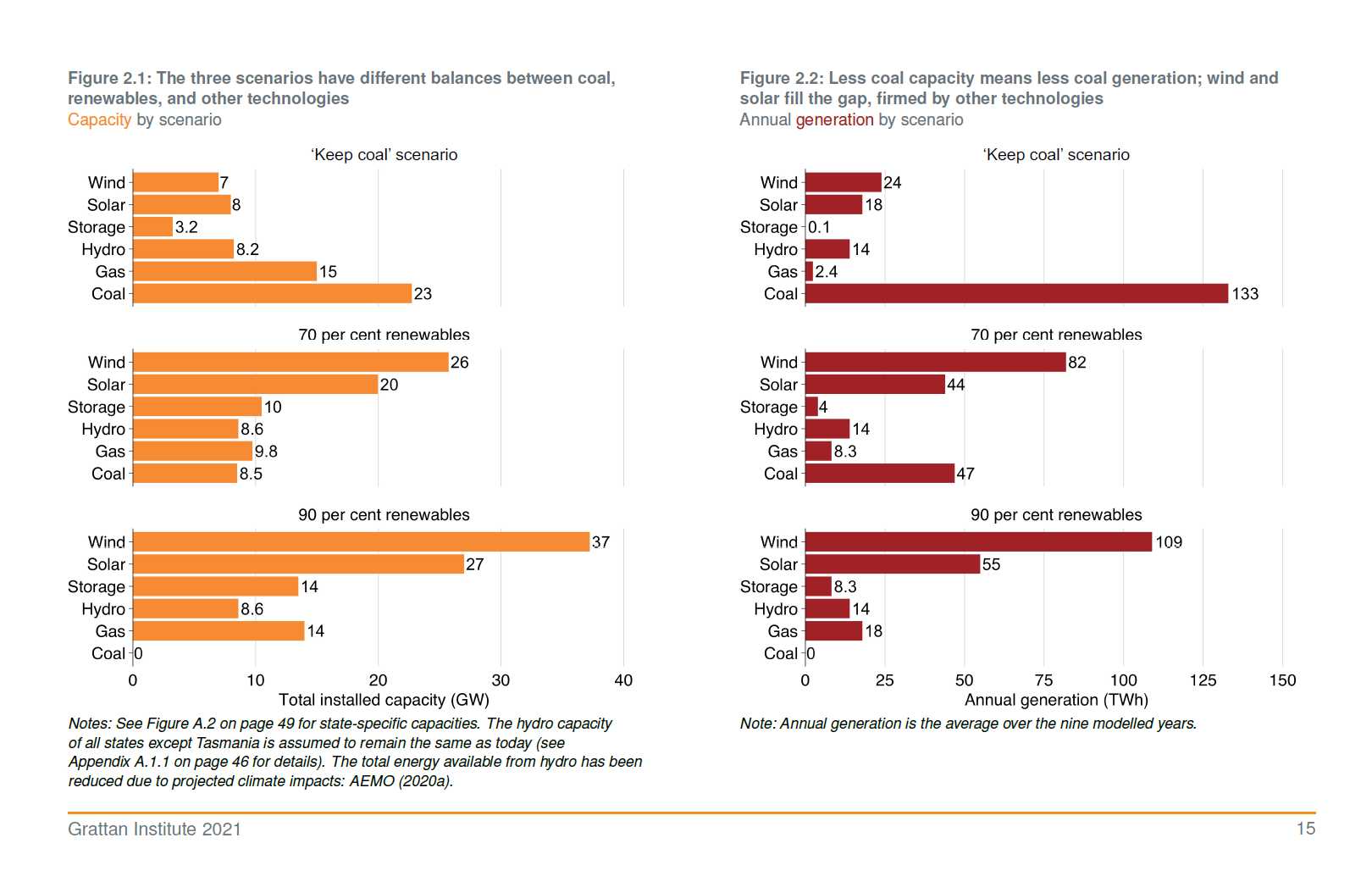

What about the remaining 10% of power supply? Grattan fills in that gap with gas-fired power generation, and urges ‘negative emissions’ as a pathway to cancelling out the very significant emissions footprint of fossil gas. This, they say, is currently the better option over other tools for balancing the final 10%. The problem is extended periods of low wind and solar output, with few viable, cost-effective long-duration storage options in Australia – what they characterise as the ‘Achilles heel’ of renewable energy.

In their ‘90% renewables’ scenario, the lowest emissions of the lot, gas supplies 18 gigawatt hours per year, averaged over the nine years modelled. That’s around 8% of total generation (including storage). It is a slight increase in the NEM’s current levels of gas generation, which was around 15 gigawatt hours in 2020, and would need an increase in four gigawatts of fossil gas capacity from today’s 10 existing gigawatts.

My first grip with this (interesting and worthwhile) report is that it doesn’t consider the pace of emissions reductions required to align with a 1.5C global temperature target. I know I bang on about this a lot, but it doesn’t seem to be sinking in: Australia’s grid needs to be zero carbon by 2030 to align with a 1.5C temperature target. But the Grattan report adds a full decade onto that, examining the question of ‘zero’ by 2040 – even in their 90% renewable scenario, there is still roughly ten megatonnes of CO2-e per year.

My first grip with this (interesting and worthwhile) report is that it doesn’t consider the pace of emissions reductions required to align with a 1.5C global temperature target. I know I bang on about this a lot, but it doesn’t seem to be sinking in: Australia’s grid needs to be zero carbon by 2030 to align with a 1.5C temperature target. But the Grattan report adds a full decade onto that, examining the question of ‘zero’ by 2040 – even in their 90% renewable scenario, there is still roughly ten megatonnes of CO2-e per year.

As a consequence, Grattan propose shifting from an ‘absolute zero’ approach to a ‘net zero’ approach – relying on ‘offsets’ to re-absorb the emissions released from relying on fossil gas to generate 8% of the grid’s annual energy. That’s my second gripe.

Grattan toy with the idea of a range of alternatives – overbuild VRE, more transmission, deep storage, demand response, hydrogen, geothermal and even fossil fuels with carbon capture. But none are as cheap as simply falling back to fossil fuels and buying offsets. “It is much easier and cheaper” to use gas and liquid fuels rather than hydrogen or electricity.

Actions to ‘re-absorb’ greenhouse gases face a range of very significant hurdles, many of which aren’t addressed in the report. Nature-based solutions are increasingly being criticised for false advertising (such as forests that were never due to be chopped down being sold as ‘avoided deforestation’), or being only a temporary store of carbon (a planted tree burns down in a bushfire, for instance). Technological carbon removal has slightly more hope for being permanent and more verifiable, but it is also far more experimental – not just expensive, but barely invented yet.

Grattan – focused far more heavily on costs and economic rather than emissions and climate through the report – do highlight that more expensive carbon offsets will make zero-emissions alternatives to gas far more attractive. As Grattan write:

“The cost of offsets is likely to rise substantially. Energy consultancy Reputex forecasts that the offset price is likely to rise to anywhere between $30 and $100/t by 2040.123 At net zero, the price will probably be much higher, given that only negative-emissions credits can be used to offset NEM emissions. And as offset prices rise, the amount of emissions-intensive generation in a net-zero NEM will fall, and zero-emissions alternatives will become more cost-competitive”.

Grattan’s report has no problem in imagining a coal-free NEM as plants retire by their use-by dates. But shutting them down early, or getting rid of fossil fuels altogether, would have been valuable goals to argue in favour of. If an extra four gigawatts of fossil infrastructure are added to the grid on the assumption that ‘negative emissions’ technologies will magic themselves into feasibility within a short timeframe, that’s an extremely bad outcome.

From our current vantage point, it might be hard to imagine caring about much other than the economic costs of the transition. But the costs of action that is too slow or too unambitious are real and significant too, and are frequently excluded or diminished in these discussions.

Everywhere in the world, the electricity grid will be the backbone of climate action, as sectors like transport, buildings and industry are electrified. That means any failures – such as overblown fossil gas development based on the assumption of its “need” in twenty years’ time, or the highly likely underdevelopment of negative emissions – will multiply in scale. It’s far better to bet on real zero emissions, and avoid sinking time and money into risky efforts to prolong the presence of fossil fuels.

Grattan’s report is interesting, and welcome. But the baseline for Australia’s grid needs to be set better – with far more regard to the safety and health risks of high emissions, and far less nervousness about high ambition and high speed.