Germany has an affordable and feasible track to reach the 65 per cent target for renewable energy production by 2030, according to a new report by German clean energy think tank Agora Energiewende.

The German coalition government raised its clean energy target to 65 per cent back in January, up from 50 per cent, to the surprise of many.

It’s considerably higher than the 36% target set by Australia’s National Energy Guarantee, and even Labor’s aspirational target of 50 per cent by 2030.

At the time, it was unclear how the German government thought this new target could be achieved – building more offshore wind by 2020 seemed impossible, although solar seemed achievable.

Now, the path is apparently clear: 12 steps to take the EU powerhouse’s current 36 per cent share of renewable electricity generation, thereby achieving the goal set by the Christian Union and Social Democrats coalition.

The plan is to follow a series of measures, from increasing production and reducing consumption of electricity, to modernising electricity grids to the extent that they can pick up and transport the additional consumption over the next twelve years.

As renewable systems are becoming more and more cost-effective, and electricity generated from older renewable systems are no longer exempt from Germany’s renewable energy surcharge, Agora’s report says that the costs for the accelerated expansion are very moderate.

“Renewable energies have not only become more and more cost-effective, but new plants are now also producing significantly cheaper electricity than new conventional power plants,” says Dr Patrick Graichen, Director of Agora Energiewende.

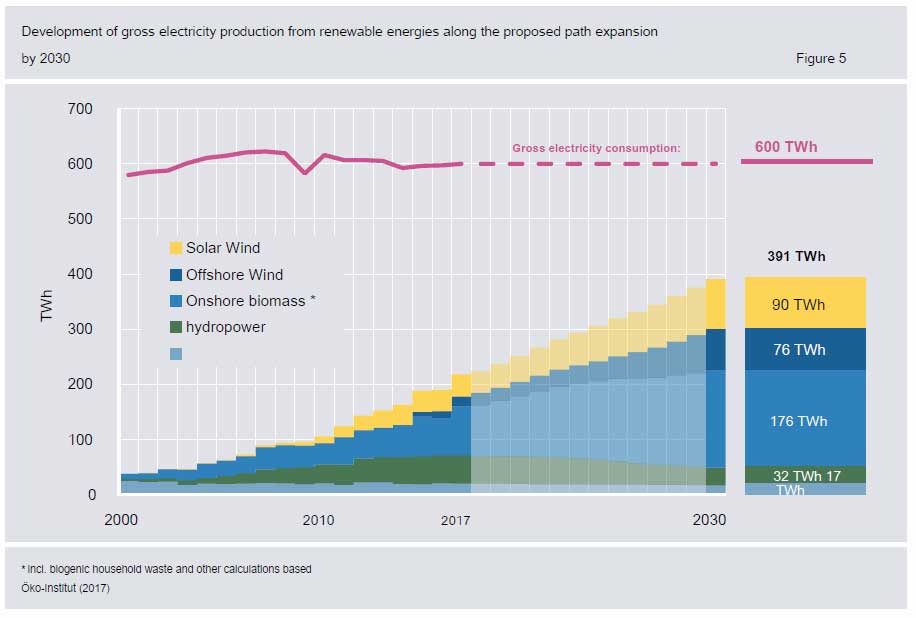

To reach the target, the report says that fundamentally, new wind and solar must be built, with a doubling in solar production and a focus on wind, both onshore and offshore.

In addition to installation of more renewable energy systems, the report says that significant reductions can be achieved by the introduction of ambitious energy efficiency measures, such as reducing demand for heating needs.

This would see a total 391 terawatts hours out of a gross 600 terawatt hours created from renewables, successfully reaching the 65% target.

To encourage this reduction, a modest increase in the EEG levy of only 0.4 cents per kilowatt hour compared to the 2017 increases is expected, ensuring competitive electricity rates in the European landscape.

“Other countries have recognized this and are now aggressively building renewable energies. Because switching to renewable energy not only involves climate protection, it also involves internationally competitive electricity generation,” continues Graichen.

Twelve measures are listed in total for the future integration of renewable energies into German electricity grids from now until 2030, most of which involve significantly improving the utilization of existing networks.

To begin with, simple measures such as comprehensive temperature monitoring of conductor cables on high voltage pylons can be implemented in the short term, reducing loss of power due to temperature fluctuations.

Similarly, it is proposed that wind turbines to meet regional quotas be built, leading to fewer network bottlenecks, reducing the need to transport electricity and, as a result, relieving burden on the grids.

Another option for better distribution of electricity in the grid can be achieved by installing active control technology in substations, which can be used to redirect power flows from heavily loaded to less loaded parts of the grid.

Finally, the paper recommends that the power grid be built with the future in mind, such as laying empty conduits and extra cables when constructing the large north-south electricity highways (HVDC lines) by the mid-2020s.

While it’s all well and good to have a plan – and the figures for renewable system production set by Agora seem achievable – Graichen says that legislation by the government’s network agency in cooperation with Germany’s four main power companies is needed to make it happen.

“This legislature must become a legislative term of the networks. The aim is to make the networks capable of handling two thirds of electricity by 2030 and about 80 per cent by 2040,” says Graichen.

“It is up to you to decide whether or not you will succeed,” he concludes.