The make-up of Australia’s new parliament cut a depressing vista on Monday.

There was Pauline Hanson, demanding royal commissions into Islam and climate science, who along with other minor party and independent Senators will most likely hold the balance of power in the Senate, with as many as 7 seats but a minimum of 3.

Hanson gave us a taste of what is to come in an extraordinary debate on ABC’s Q&A, which was punctuated with the sort of ignorance and ideology we often see in the energy sector – see South Australia.

In the government, the Coalition led by Malcolm Turnbull has elevated more conservatives to the front bench. Zed Selseja, a conservative who opposes gay marriage and weekend penalty rates, is minister assisting social services.

Matt Canavan, a conservative who dismisses climate science, is appointed resources minister responsible for the coal industry and building dams in northern Australia. Be under no doubt about Canavan: the only energy that matters to him, he has said often, is cheap energy, dirty or not.

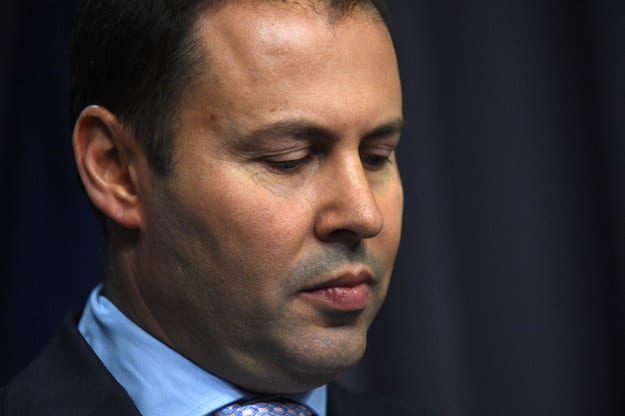

Josh Frydenberg, another conservative, a fan of nuclear and a man dubbed “Mr Coal” by Australia’s most extreme right wing commentator, is given stewardship of a new super-ministry combining environment and energy. Not a bad idea in itself, but it depends on who is running the show.

Frydenberg is, as we have discussed, a big supporter of nuclear. Indeed, he likes to thinks big in terms of base load energy, and in his relatively short time as energy and resources minister has repeated the talking points of the coal industry, such as “coal has a strong moral licence,” and attacked green “activist groups.”

In an appearance on the Murdoch TV’s The Bolt Report last year, he was dubbed Mr Coal by Andrew Bolt – an admirer of Hanson’s attack on Islam and a supporter of Canavan’s criticism of climate science who continues to hold a thrall over conservative politics.

It looks like a bad start, but not all are despairing. The Australian Solar Council, for instance, noted that Frydenberg – unlike other Coalition candidates – actually turned up at a candidates’ forum in Box Hill in Melbourne in mid June to talk about climate change.

According to the some of those present, Frydenberg impressed because – they said – he appeared to understand that the world was changing, recognised that coal was in deep trouble, and grasped the fact that new technologies – battery storage in particular – were inevitable and the way of the future.

That’s not the man that the incumbent energy industry think they have in the minister’s office. The Queensland Resources Council was boasting of “scoring a trifecta” with the appointments of Frydenberg, Canavan and former environment minister Greg Hunt as minister of Industry and Innovation.

“The resources sector requires steady safe hands to ride through the commodities downturn and in the face of a relentless green activist campaign,” QRC chief Michael Roche said in a statement.

But there is a precedent here for a surprise. Mike Nahan, the former head of the ultra conservative and highly influential think tank, the Institute of Public Affairs, arrived in the West Australian energy portfolio with a similar disdain for renewable energy, a fascination for nuclear and a none-too-convincing “epiphany” on climate change.

But Nahan has been a revelation. Faced with the basket case economics of the WA fossil fuel grid, a microcosm of the national grid, with layers upon layers of subsidies and market rules pitched in favour of the incumbent fossil fuel oligopoly, Nahan has now recognised that the future energy system will be based around solar and storage.

And he has started to put in train a makeover of the energy system, pulling back layers of subsidies that saw diesel plants built with taxpayer funds but never used, and instructing the government-owned utilities to shut down coal and facilitate the uptake of solar and battery storage.

Over the next few months, Frydenberg has the opportunity to do the same in the national market, which has become completely untenable.

The energy industry – the networks, generators and miners – presumably think they have a man who can perpetuate the largesse of a system that is tilted in their favour.

Australians are already paying more than any other country for their delivery costs (networks), and now wholesale prices – thanks to record gas costs – are also soaring. As well as that, as Bruce Mountain reveals today, the big retailers are fattening their margins too.

Indeed, the consumers are under assault on all fronts. But they, more than anyone, understand that the system is changing and the opportunities – in producing and storing their own electricity – that are before them.

The incumbent utilities know that too, but as various regulators launch inquiries into the “stability of the system,” the powerful oligopolies are seeking to may hay while the sun shines and are resisting change, opposing market rule fixes, fighting network spending cuts in the courts, and exercising their dominance over the markets.

They are asking for handouts at every turn – payments to close power stations, payments to keep them open (in the form of capacity markets, a system that Nahan is now trying to wind back in WA and which the EU and the UN have criticised as yet another fossil fuel subsidy).

At every turn, it seems, the energy incumbents are seeking to hold the market to ransom – a point that the South Australian government has realised, as it becomes increasingly vocal about the failure of the national market.

It is furious about the monopoly of the incumbents, and the inability of the regulators to reign them in. It is as though the industry is setting the state up for failure, with enthusiastic applause from many in the media.

The first thing that Frydenberg could do, as environment minister, is to write an environmental outcome in the National Electricity Market rules, which are scandalously absent. Coal and gas-fired plants are continuing to operate without being responsible for their environmental cost. That remains the biggest subsidy of all.

No decision about network planning or generation is required to consider an environmental outcome, which is why the pricing regulators can escape, with impunity, with ascribing a solar feed-in tariff that takes no account of the technology’s many benefits.

Australia is not alone in facing these questions, but it does find itself at the cutting edge of this energy revolution. A new analysis published by Cambridge University gives one of the most detailed insights into the rorts and subsidies embedded in the energy system.

In response to the oft-asked question about the need for subsidies and policy support for solar and wind, it notes that the current infrastructure was subsidised over many years and tailored to the incumbent technologies.

That infrastructure refers to the physical infrastructure, such as poles and wires and fossil fuel generators, but also to the regulatory, political and economic framework that serves institutions, such as the energy market, the utility regulatory system, and the power, grid, and other massive projects built with government funds.

“The short answer is that the electricity market does not work,” the researches noted – and as the South Australian government is pointing out.

The total subsidy amount for fossil fuels in 2013, found by adding producer subsidies to post-tax subsidies, is in the range of $US5.5–$US6 trillion dollars. The total renewable subsidies (US$120 billion) were only about 2% of the total fossil fuel subsidies in 2013.

“Oil & gas received 10 times the annual amount than all renewables received, and they received it for 6 times longer and are still receiving it,” the report notes.

“Oil & gas received 10 times the annual amount than all renewables received, and they received it for 6 times longer and are still receiving it,” the report notes.

“This puts renewables at a significant competitive disadvantage, even if they can offer a competitive price. The technologies and economics are not at issue, rather the question is whether policy makers will be able to steer energy subsidies to match the future they profess to choose.”

The study noted that DNV-GL conducted a survey of 1600 people in the energy industry across 71 countries. About half of the respondents believe that the electricity system could transition to 70% renewable generation with the next 15 years. 80% believe it will be achieved before 2050.

The overall perception – as the head of the Chinese national grid has pointed out – was that achieving 70 per cent renewables is not mainly a technical or an economic question, but rather a political one, meaning that government support is crucial.

Transitioning to a primarily renewable electricity system is changing the fundamentals of the business. It requires fundamental changes in the electricity market, power sector regulations as well as the need to shift to a systems approach in maximizing synergies between renewable technologies.

“Political leadership can also help all industry players to pull together to achieve an orderly transition of the electricity system,” the report says. The chances are that Frydenberg knows this. But can he, or does he want to, convince his conservative peers that this is what he should be allowed to do.