Australian mining and energy giant Fortescue announced late on Wednesday that its ambitious green energy goal – to produce 15 million tonnes of renewable hydrogen annually by 2030 – will be placed on hold.

As part of a broader restructure, the company will also merge its mining and energy divisions, and slash 700 jobs across its business.

The news will disappoint those who’ve eagerly awaited the emergence of a green hydrogen sector in Australia. Fortescue’s executive chairman and founder, Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest, has been an outspoken supporter of the technology.

But since the announcement, Forrest has been quick to reject claims the company is walking back from its green hydrogen dreams more broadly, telling Nine Radio in Perth on Thursday:

We just have to work out now how to produce it cheaply enough.

Fortescue’s announcement reinforces the fact that one company can’t do it alone – Australia needs a coordinated approach to supporting future green industries – including renewable hydrogen.

Developing renewable hydrogen at scale – like any industry – will require both national and global action to build demand, by supporting new technologies and lowering the risk of investing in early projects. Over time, this will bring prices down.

Hydrogen has a role to play – if we can make it cheaply

Green or renewable hydrogen is produced by “electrolysing” or splitting water into its component elements hydrogen and oxygen using renewable electricity.

This is in contrast to non-renewable “blue hydrogen” which is extracted from natural gas using steam in a process called “steam methane reforming”.

Renewable hydrogen’s current high cost of production has been a key element of the industry’s sluggish start.

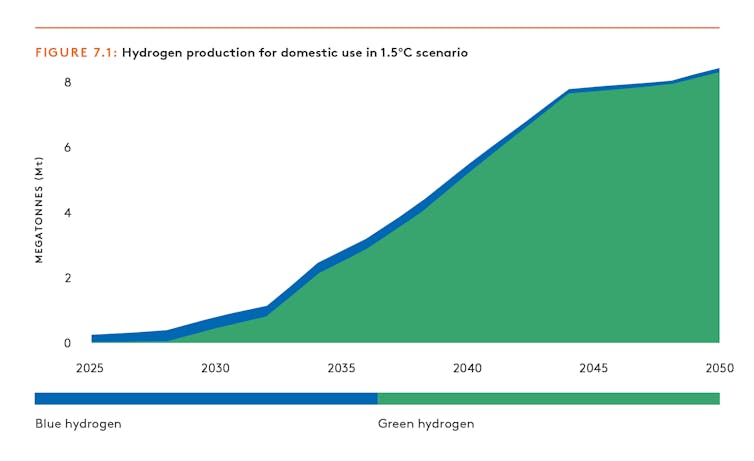

At Climateworks Centre, we’ve modelled a range of different scenarios across the whole economy to work out how Australia can best reduce its emissions at the lowest cost.

Our modelling shows renewable hydrogen can indeed play a lead role in Australia’s energy future. It becomes particularly important for transitioning industries that can’t be electrified, such as ammonia and alumina production, and heavy transport. But only if it becomes commercially viable to produce.

This is where the Future Made in Australia policy will serve as an important “net-zero” filter by setting out tests which must be passed to unlock targeted government investment.

The policy includes an economy-wide framework to determine which industries need government support to incentivise private investment at scale. But it acknowledges we can’t do everything, everywhere, all at once – we must prioritise our actions.

Renewable hydrogen has already been assessed by Treasury as an industry that requires support under the policy. This is because it meets two key net zero “tests” – it offers Australia a sustained comparative advantage in a future net zero global economy, and needs significant public investment to reduce emissions at an efficient cost.

This should come as no surprise. Australia has a clear comparative advantage in the production of renewable hydrogen, with a skilled workforce and abundant renewable resources and land.

Renewable hydrogen is also a foundational requirement for other products we can produce and export. Modelling by CSIRO and Climateworks for the Australian Industry Energy Transitions Initiative has explored these uses.

It found that in the short term, hydrogen could help decarbonise ammonia production (used for fertiliser and explosives), and potentially also mining haulage and alumina calcination – an important step in refining aluminium. Longer term, steelmaking and freight could also require significant volumes of hydrogen.

Slow out the gate

Despite this potential, the market for hydrogen has been slow to get started.

A number of factors have made private investment challenging. Limited data from current large scale green hydrogen projects means there’s some uncertainty on how quickly the cost of producing renewable hydrogen will come down.

Currently, there’s also limited access to the large amounts of low-cost renewable energy required to make hydrogen projects commercially viable.

Without established local and global demand, public investment is needed to kick start this industry at scale.

Fortescue’s announcement indicates it is likely experiencing some of these challenges. But the supports contained in the Future Made in Australia policy may eventually help alleviate some of these pressures on it and other companies in the emerging industry.

A$4 billion to bridge the cost of producing renewable hydrogen and the market price with a hydrogen production credit via Hydrogen Headstart, plus a $2 per kilo hydrogen production tax incentive both aim to improve the investment outlook for green hydrogen projects.

By providing some price certainty for each kilo of renewable hydrogen produced, the government will share the risk with potential investors, making the projects more bankable. Both of these supports will be paid over a ten-year period.

Fortescue’s setbacks reinforce the need for support

Getting to net zero is complex and will require ambitious, coordinated action from government, industry, and finance.

Bold action on climate isn’t a choice, it’s an imperative. To do challenging things quickly, each part of the economy must step up. If we get this right, generations of Australians can work in and benefit from a net-zero nation run on renewable energy, with a thriving renewable hydrogen industry.

Fortescue has long taken much-needed first mover risks to drive attention and action in the global and Australian renewable hydrogen market. This week’s news is a setback, but shouldn’t be seen as a death knell for the nascent industry or for the government’s bold ambitions.

Rather, it highlights the gap that government support aims to fill by coordinating and unlocking finance, and funnelling it in the right direction.

Kylie Turner, System Lead, Sustainable Economies, Climateworks Centre and Luke Brown, Head of Policy and Engagement, Climateworks Centre

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.