With the next federal election looming on the not-so-distant horizon, temperatures have flared both inside and outside Parliament House in Canberra as the Albanese government becomes increasingly desperate to clear its legislative to-do list.

One source of frustration has been demands from key cross-benchers for the creation of a ‘climate trigger’, a potentially landmark reform to Australia’s national environmental laws and which could be key to stopping the growth of Australia’s fossil fuel industries.

Albanese’s refusal to negotiate on the introduction of the climate trigger – a policy he once personally supported – has seen him compared to former prime minister Scott Morrison and labelled a ‘bulldozer’.

So, what exactly is a ‘climate trigger’?

To understand the concept of a ‘climate trigger’, it is important to first understand a key piece of Australia’s national environmental laws, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (the ‘EPBC Act’ for short).

The EPBC Act was first legislated in 1999, with the goal of implementing commitments Australia had made under a range of international environment treaties and conventions.

To do this, the EPBC Act designates nine ‘matters of national environmental significance’, often corresponding to one of the international treaties, but can include any environmental matter the parliament considers worthy of protection or consideration.

This list of matters currently includes Australia’s wetlands of international importance (including wetlands protected by the Ramsar convention), threatened species, listed migratory species, areas of world or national heritage significance, and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. It also includes any ‘nuclear actions’, effectively prohibiting the development of nuclear power stations in Australia.

Under the EPBC Act, any new development that proposes to have a significant impact upon one or more of the ‘matters of national environmental significance’ must first obtain approval from the Federal Environment Minister.

After considering the impacts of the development on the ‘matter of national environmental significance’ and weighing them up against the need for sustainable economic and social development, the minister has the power to approve a project, or they can reject a project if they determine the project’s impact would be unacceptable. The minister can also approve the project under certain conditions designed to reduce the project’s impact.

As a recent example, a property development proposed to be built on top of a Ramsar listed wetland? Rejected.

In theory, it sounds great. In practice, the EPBC Act is quite restrictive, as the minister is limited to considering only a development’s impacts on the listed matters of national environmental significance and economic considerations more often than not outweigh those impacts.

Crucially, the EPBC Act does not include climate change as a ‘matter of national environmental significance’, and the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions on the environment – which are now well understood to be potentially devastating – are totally ignored.

Last year, the Federal Court confirmed that climate impacts can be ignored under the EPBC Act after rejecting an appeal against the approval of two new coal mines. Relatedly, the Federal Court has also held that the minister has no obligation to protect young people from the impacts of climate change when exercising their powers under the EPBC Act.

As a result, around two dozen new fossil fuel projects have been approved under the EPBC Act by the Albanese government – decisions inconsistent with its stated commitment to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees but acceptable under our current environment laws.

Leading climate law expert, Melbourne Law School professor Jacqueline Peel, described the EPBC Act as “not fit-for-purpose as a legislative tool for protecting the Australian environment and nature from the harmful effects of one of the greatest environmental threats we face, namely climate change.”

It is in this context that the concept of a ‘climate trigger’ has emerged as a way to fill the evident gap in the environment laws, potentially having climate impacts added as a new matter of national environmental significance.

The EPBC Act would be reformed so that any new development resulting in a large increase in greenhouse gas emissions would activate a ‘trigger’ for the project to be referred to the Federal Environment Minister for review. The minister could then use new powers to block any project that would lead to an unacceptably large increase in emissions.

As an example of how it could work, under the Australian Greens’ proposed amendments to create a climate trigger any proposed project that would emit more than 100,000 tonnes per year would automatically be blocked, and any project proposing to emit between 25,000 and 100,000 tonnes per year would be subject to the approval of the Federal Environment Minister.

Independent senator David Pocock has supported the introduction of a climate trigger, as have a large number of environment groups.

Unsurprisingly, mining companies, business groups and the Coalition have all opposed proposals for a climate trigger.

What is the Albanese government’s position?

Federal Labor has also opposed the introduction of a climate trigger, arguing that greenhouse gas emissions are better regulated through dedicated climate policies like the Safeguard Mechanism.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese recently told a press conference in Canberra:

“With regard to climate trigger and other things that they’re raising, I’ve made it clear… that I don’t support adding a trigger to that legislation. Climate issues are dealt with through the Safeguard Mechanism. We’ve dealt with that. We have a target of 43 per cent and we have a vehicle for emissions of large emitters, as well as part of that program.”

– Anthony Albanese, 16 September 2024.

Why is a climate trigger still important?

A climate trigger would tackle greenhouse gas emissions in two ways that are critically different to existing policies like the Safeguard Mechanism.

Firstly – a climate trigger would capture fossil fuel projects before they even start. As the EPBC Act applies during the approval process for major developments – like new gas projects or coal mines – projects cannot proceed if the Federal Environment Minister refuses to provide consent to the development under the Act.

Once a new gas project is already up and running, especially if that project is exporting gas to be burnt overseas, all of its emissions are essentially locked in, as no government will turn around and subsequently revoke approvals due to threats of litigation and cries of ‘sovereign risk’.

This means a climate trigger could serve as a powerful tool for stopping new fossil fuel projects from even getting off the ground.

The second key feature of a climate trigger is it could consider the global implications of new fossil fuel projects, including the emissions created through the use of the fossil fuels Australia exports overseas.

As it is currently designed, the Safeguard Mechanism only applies to ‘Scope 1’ emissions. These are the emissions that are directly produced a facility’s operations within Australia. This would include the emissions produced from the burning of coal in a steel furnace at Port Kembla, or the methane that escapes from a gas processing facility in Western Australia.

But emissions produced from the burning of coal or gas after it has been exported from Australia are not covered by the Safeguard Mechanism. These ‘Scope 3’ emissions can be significant, accounting for around 90 to 95 per cent of the total emissions footprint of exported coal or gas.

Take, for example, the emissions footprint of Chevron’s Gorgon LNG facility in Western Australia – the largest project covered by the Safeguard Mechanism. According to Chevron’s own data, in 2022-23, the project processed 1.15 million terajoules of fossil gas – which would convert to more than 64 million tonnes of carbon dioxide when burnt.

Yet, Chevon was only responsible for 8.2 million tonnes of emissions from the facility under the Safeguard Mechanism – only the emissions that were released while the gas was processed in Australia. The ‘exported emissions’ are ignored entirely by the Safeguard Mechanism, despite the fact that it makes no difference whether the emissions occur in Australia or in another country: they have the same contribution to global warming.

The big picture

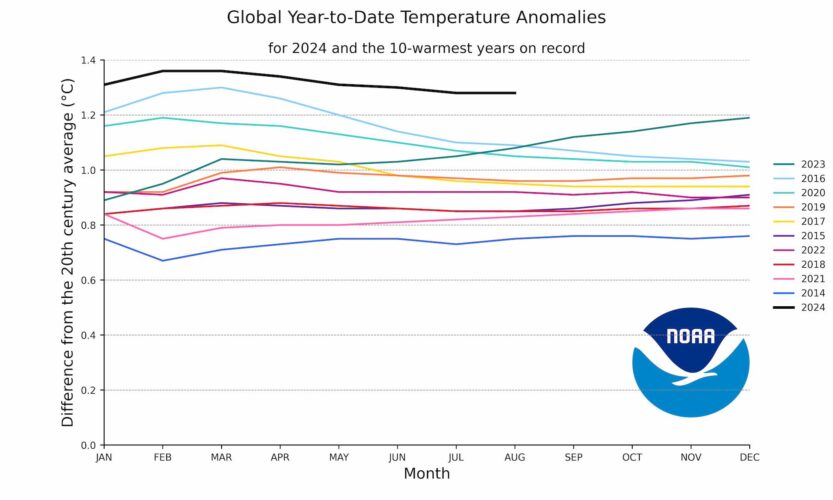

The need to urgently act to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions is abundantly clear. We are living through a period of particularly intense climatic conditions that are pushing temperatures and the climate system to new volatile extremes. Last year was the warmest year on record, and it is virtually certain that 2024 will immediately break that record.

Stopping the trend requires an immediate halt to the development of new fossil fuel projects. The Albanese government says it is committed to a 1.5-degree warming goal, but it contradicts that commitment every time it approves a new coal, gas or oil project.

A climate trigger would fill the void that exists within Australia’s national environmental law and would provide the government with a powerful tool for halting fossil fuel projects before they start.

It is probably the most meaningful piece of climate policy Australia can implement and it should not be so readily dismissed by political leaders.

This article was originally published on Tempests and Terawatts. Reproduced here with permission. Read the original version here.