The demand forecasts in the Integrated System Plan’s Step Change scenario will not be achieved without more targeted policy, particularly in regard to industry electrification and specifically electrification of process heat.

In general the Australian Energy Market Operator seems to compartmentalise demand forecasts and ISP supply. In my opinion, public understanding could be enhanced by linking the two in a more accessible way.

Less demand generally means less pressure on price.

Spot prices are likely to be more volatile as renewable penetration increases, but consumers have low visibility to those prices and therefore don’t see the price signal.

At first glance there appear to be regulatory barriers to efficient demand response. Longer term, if investors believe current price patterns will persist we should see the growth of seasonal demand. However, in a rapidly changing world few managers will have the required confidence.

Finally, an implication of the numbers is that retailers who in general make the the vast bulk of their profits from supply to household customers are unlikely to see any volume growth, indeed may well see volume declines if the ISP step change forecasts come to pass.

As networks have shown, a lack of volume growth is not a problem, but still most management want growth.

Supply is based on one third growth in demand to 2035

Higher demand is generally positive for prices. The Step Change or base case scenario of the ISP sees demand growing from about 209 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2025 to about 285 TWh in 2035, an increase of 1/3.

Most of the increase is from assumed production of green hydrogen, business and residential electrification and EVs (electrification of transport).

In my opinion, both the hydrogen and electrification increases will not happen without policy support. And in my opinion too much policy attention has been paid to hydrogen and not enough to business electrification.

A large, even dominant area of business electrification would be replacing gas with electricity in process heat. For this to be economic either the gas price has to be much more than it is right now, or electricity has to be cheap. A price of $50 MWh electricity = $13.9/GJ gas (divide by 3.6).

Like other areas, business won’t commit just because the electricity price is low today, they want confidence that prices will be low for long enough to get a return on capital.

A separate issue is that demand generally only responds at a glacial pace to changes in price. It’s interesting because I am a financial analyst and not an economist, but when I read about price elasticity, that is the response of demand to a change in price, it’s generally about the amount of demand response, not the speed of it.

In electricity, we would like some demand response to be essentially instantaneous, much like a battery. However, even if the investment is modest and the return on investment better than building say a battery, we haven’t as yet seen much demand response.

In truth, we don’t know because it mostly appears not to be measured, but the view is that it doesn’t happen in the National Electricity Market (NEM). The AEMC rule makers might ask themselves if the rules are not unduly cumbersome.

Although immediate short term demand response is of interest so is seasonal demand. And it’s no good as Peter Dutton mutters in his negative, dog-whistling style to say it should all be baseload.

That thinking is, as you would expect from the Queensland LNP, very old fashioned and stuck in the past. The fact is that many businesses from tourism to agriculture are seasonal for one reason or another. What we need is seasonal energy intensive businesses.

And to bring electrification of process heat and demand response together, the point is that much process heat can be wound up or down without undue difficulty. Alumina boilers, cool room air-conditioning, paper processes, food and beverage processing can generally be ramped up and down at only moderate cost.

Yet another issue is that many consumers are not directly exposed to spot prices. In particular the behaviour of consumers is going to be driven in part by price signals provided by network tariffs. My issue with that is that networks don’t have a sufficient incentive to respond to customer needs in designing network tariffs.

Network tariffs are designed effectively in consultation with the AEMC and the AER. No matter how good intentioned management at the AEMC and the AER they too don’t have any direct responsibility to customers.

Customers cannot choose their regulator, they cannot choose their network, their only choice, which of course they exercise vigorously is to minimise their involvement with the system by putting on firstly rooftop solar and increasingly batteries.

AEMO could link demand and supply better in ISP outputs

AEMO does a ton of work on demand forecasting and Methodology AEMO also publishes a forecast accuracy report. AEMO of course also releases lots output related to the ISP. A spreadsheet summary of the annual supply side in terms of energy and capacity is found at generation and storage outlook.

Additionally for those like myself, who think this is important enough to get into the weeds, AEMO also publishes half hourly traces of REZ wind and solar capacity factors per megawatt (MW) of capacity and half hourly demand traces all the way out to the 1950s. ITK price forecasting models make much use of this data.

If you have a Plexos license, and it’s so expensive that very few can have such a license, you can see how it all fits together. For those of us without Plexos, AEMO could perhaps improve things by showing how the demand and supply forecasts fit together.

Some of things I can’t easily find in the data:

- – A reconciliation of demand and supply. Losses are reported in the demand category but not spillage;

- Exported rooftop solar supply.

- – Demand response is not measured, although some of the demand modelling does incorporate some price assumptions.

Despite these limitations I must acknowledge the excellent data that AEMO does provide. Still, the demand portal is sufficiently convoluted that AEMO itself has an instructions in how to use its page.

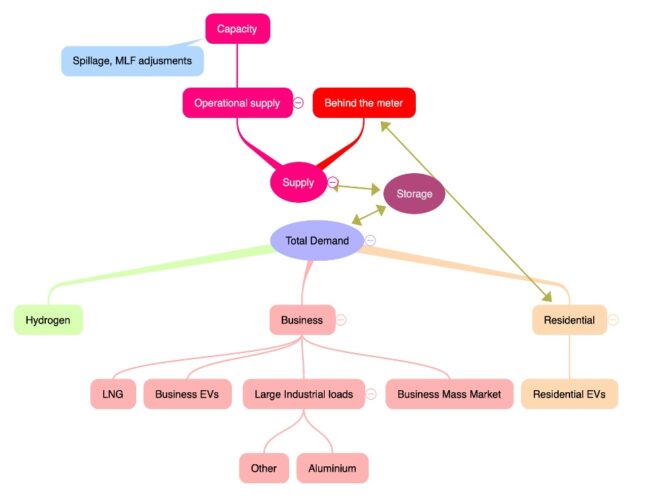

I’ve taken the liberty of using a figure taken from AEMO’s demand methodology document and extended it. Even so things like auxiliary loads (self consumption by a coal or gas generator) have been ignored.

Supply & demand. Source:ITK

Note that this figure is conceptual and does NOT in any way indicate the size of a category. The olive green lines show some of the complexities. Behind the meter generation is still only an estimate as far as I know.

More importantly, the quantity of demand and the quantity of some supply is driven by price. However, as far as I can see the main visible impact of price is in substitution and new capacity. High prices incentivise faster growth of behind the meter solar.

Equally, the figure shows neither geography nor demand response. The lower the long run cost, the higher demand in the long run and vice versa.

AEMO’s demand forecasts break from history, but carry risk

Using AEMO’s step change demand forecasts and rearranging the numbers to suit my training as an accountant, and also trying to summarise but not hide the data, results in the following table.

Supply & demand. Source: ISP Stepchange

On this set of numbers as a residential retailer you might be a bit gloomy. It’s one thing to sell electricity to households but its another thing altogether to ask them if they want to join your VPP because 2/3 of household demand will be self supplied as a class, and the total quantity the residential sector buys from the grid is forecast to decline.

That said, the average is a combination of some householders who will be net producers and probably 30-40% of households will still be buying 100% of their requirements from someone else. Still, about 80% of big gentailer retailing profits come from the household sector, so these forecasts will impact the multiple paid for current earnings.

Growth is from new and hard to estimate sectors

The grim outlook for operational residential demand is at odds with the overall forecast where demand grows about 1/3 over the next decade mainly from hydrogen, EV charging and electrification.

Each of these is a new source of demand and so the extent and the timing of when it takes off has inherent uncertainty. For the next few years in terms of supply it doesn’t matter, what ever the demand outcome the coal generation has to be replaced. Still, prices will be higher if demand is growing.

When you look at the numbers the key value segment in the future may move away from the household towards the business mass market, and for operational supply the business mass market may be 3x-4x the volume of the household market.

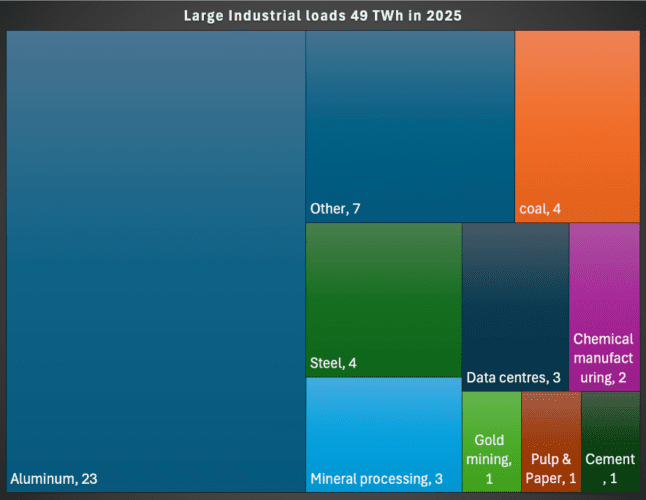

Large industrial loads – aluminium is maybe 40%

Although AEMO doesn’t provide it I’ve done a bit of a back of the envelope allocation of large industrial loads by industry. It is only back of the estimate and any individual segment other than aluminium or data centres could be out by a factor of 100%.

Large industrial loads. Source: ITKe

The data centre estimate is based on 300 MW of demand in 2024, which AEMO used actual metered data to estimate. Given all the hype around data centres it’s useful to have that 2023 baseline.

The aluminium number will be within about 15%, and more likely to be lower rather than higher, but probably not less than 20 TWh. Mineral processing includes Roxby Downs, zinc refining. The gold mining estimate could be too low but these estimates are just for the NEM with much gold mining in WA and or off grid. Steel is basically electric arc furnaces.

Other than Data centres it’s hard to see much organic growth from these sectors. It’s true that existing facilities can be electrified, that is mostly replacing typically gas fired process heat with electric resistive or heat pumps, but in terms of new mineral processing facilities, new coal mines, new aluminium smelters maybe not so much.

Or at least only if the electricity price is a major driver of global competitiveness such as with aluminium and renewable power electricity is cheaper than global comparisons. Eventually, hopefully, the coal demand for electricity will go away.

EVs, heat process and hydrogen offer flexible demand

It’s well known that green hydrogen takes a lot (50 KWh/kg) of electricity in the electrolysis process and about 7 kg of H2 to get 1 GJ of energy.

If the process was cheap enough, and the transport was cheap enough Australia, and particularly QLD, WA or the Northern Territory would be really well suited to make hydrogen and in particular hydrogen manufacturing could be wound up during the day and in the Spring and be wound down at other times.

However, I remain cautious about green hydrogen economics, particularly in the export markets.

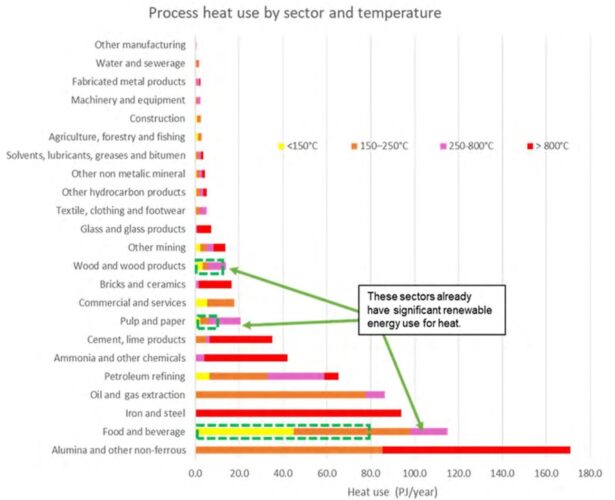

Process heat needs more government focus

Arguably a better source of flexible demand that could really take advantage of Australia’s low cost solar is process heat. It’s also a sector where good(targeted, tested and measured) policy could result in business support. Unlike hydrogen, process heat is already all through the business sector from industrial loads to abattoirs.

ARENA commissioned a process heat report that was published in 2019. Since then next to nothing has happened. Perhaps that is because of hydrogen hype, a typical example of a big new idea/dream dominating the hard work required to improve the existing situation.

In 2018 around 730 PJ of energy was going into process heat and of that maybe 45% was using temperatures less than 250 C. The cost of this heat to industry was in the order of $7bn.

The following figure shows the breakup, and yes, it’s a copy of a copy.

Process heat. Source: ARENA

To put it in context 730 petajoules (PJ) is about 200 TWh which is of course roughly equal to current electricity consumption in the NEM. From that perspective it’s a far bigger opportunity than transport.

In raw terms economics can still be a problem. As mentioned, $50/MWh for electricity is equivalent to $13.9/GJ for gas (divide electricity price by 3.6 based on 3.6 GJ = 1 MWh). So that’s still expensive if you have to contract a PPA. But given the excess solar currently available for free the economics look a lot better.

Based on the ARENA study the most attractive options may be where less than 100c temperature uplift is required, in which case heat pumps can do the job.

There is a strong body of thought that, given a bit of space, process heat can be economically stored in some medium, eg bricks, sand or graphite, and bricks may be the most economic.

The storage cost is way, way less than batteries no matter that batteries themselves get cheaper by the day. Process heat becomes totally uneconomic the instant you want to transport it, or do anything with it except using it as heat.

But for boilers, bakeries, meat processing, alumina digesting and a few other industries that Michael Liebrich could probably rabbit on about far better than me, for those industries the economics of storing heat are ok.

Even without the heat storage provide the gas facilities can be retained, using solar to replace part of the gas used in the process heat can still make a big difference. And of course we can build more solar to support that industry just as fast as we can grow demand.

Networks don’t have customers, but send price signals

A barrier to consumers seeing the price signals provided by the spot market is provided by networks. In general network regulation disincentivises innovation. Monopolies engender distrust by their nature. Australia chose the British system of electricity regulation as compared to the US system.

In the British view electricity supply consists of the market facing customers and generators, and on the other hand the monopoly providers, that is the wires and poles, or the gas pipes. Competition is the way in which market facing business self regulates but for monopolies there is more explicit regulation.

In contrast by and large the USA system provides some regulatory oversight on the entirety of the vertically integrated business and the wires and poles are treated as part of the same business as generation.

As best put by Bruce Mountain this has therefore meant that the network customer is in fact the regulator, which in Australia is the AER and the rules are more or less determined by the AEMC.

Every system has its strengths and weaknesses. From an IT point of view the separation means a lot of overlap between the network which sees a meter and a retailer that sees a customer. Networks don’t charge customers directly they charge the retailer supplying the customers.

However, what I wish to emphasise is that network tariff design basically doesn’t necessarily take any account of what consumers want.

Network owners design tariffs to achieve value for their owners, and the AEMC and the AER contribute to tariff design based on what they, as lawyers and regulatory economists think is in the best interests of consumers and society. So network tariffs are ultimately based on theoretical, normative, principles and are not market tested.

To hear more about demand response, please listen to the latest episode of the Energy Insiders podcast, a discussion with Chris Hutchinson of Enel X.