The preliminary report on energy prices released last week by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) suggests that the consumer watchdog is concerned about almost every aspect of Australia’s electricity industry.

It quotes customer groups who say electricity is the biggest issue in their surveys, and cites several case studies of outrageous price increases experienced by various customers.

The report is long on sympathy about the plight of Australia’s electricity users. But the true picture is even worse – in reality, the ACCC’s assessment of Australia’s energy prices compared to the rest of the world is absurdly rosy.

Australia has internationally high energy prices

The ACCC quotes studies from the Electricity Supply Association and the Australian Energy Markets Commission (AEMC) to compare electricity prices in Australia with those in other OECD countries. But the ACCC’s comparison is based on two-year-old data, and badly underestimates the actual prices consumers are paying.

The AEMC’s analysis assumes all customers are on their retailer’s cheapest available offer. This is an obviously implausible assumption, and gives a favourable impression of the price that customers are paying.

As previously pointed out on The Conversation, the Thwaites review – which looked at customers’ actual bills – found that in February 2017 Victorians were typically paying A35c per kilowatt hour (kWh) – 42% more than the AEMC’s estimate.

What’s more, we know that Victoria’s electricity prices are lower on average than those in South Australia, Queensland and New South Wales, and hence below the Australian average.

A part of this 42% gap – around 15% – is explained by the latest price increases that are not included in the ACCC’s comparison. But this still leaves a 27% gap between what the AEMC assumes and the evidence of actual prices.

This begs the question: why did the ACCC not recognise the widely known flaw in the AEMC’s analysis?

The real problem is overbuilt network infrastructure

The report estimates that rising network charges account for more of the price increase than all other factors put together. There is no doubt that network charges are a real problem at least in parts of Australia, although their significance relative to retailers’ costs is contested territory.

But why would distributors build far more network infrastructure than they need? And why have government-owned distributors built far more infrastructure than private ones, despite having no more demand?

The answer to this perplexing question is to be found in part in Australia’s “competitive neutrality” policy. This is Orwellian doublespeak for an approach that is neither neutral nor competitive.

Under this policy, government-owned distributors are regulated as if they are privately financed. This means that when setting regulated prices, the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) allows government distributors to charge their captive consumers for a return on their regulated assets, at the same level as if they were privately financed. That is despite the fact that private financing is much more expensive than government funding.

It’s no surprise that when offered a rate of return that far exceeds the actual cost of finance, government distributors have a powerful incentive to expand their infrastructure for a profit. This “gold-plating” incentive is a well-known in regulatory economics.

Regulators, the industry and their associations have explained higher spending on networks in a variety of ways: higher reliability standards; flawed rules; flawed forecasting of demand growth; and the need to make up for historic underinvestment.

But was there ever historic underinvestment? A 1995 article co-authored by the current AEMC chair concluded that distribution networks had been significantly overbuilt. That was more than two decades ago, government distributor regulated assets are at least three times bigger per customer now.

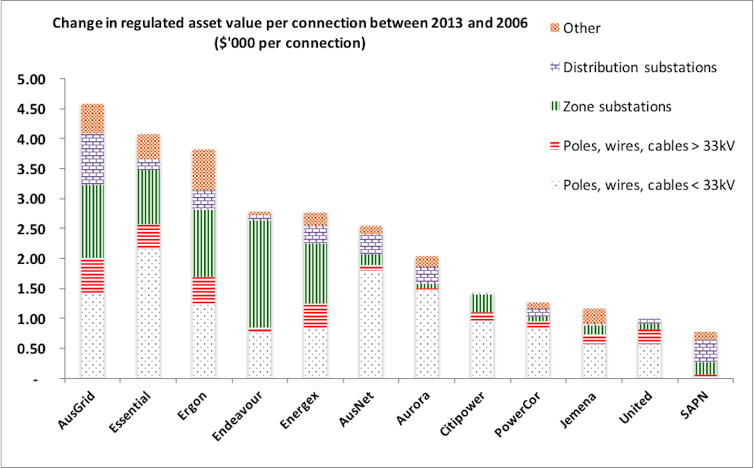

The chart below – based on data from the AER’s website – examines how the 12 large distributors that cover New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia spent their money on infrastructure between 2006 and 2013.

This period covers the last five-year price controls established by the state regulators, and the first control established by the AER. It was during this time that expenditure ballooned. The monetary amounts in this chart are normalised by the number of customers per distributor.

The first five distributors from left to right (and Aurora) were owned by state governments and the others are privately owned. A clear pattern emerges: the government distributors typically built much more infrastructure than the private distributors.

And the government distributors focused their spending on substations, which are much easier to build (or expand or replace) than new distribution lines or cables.

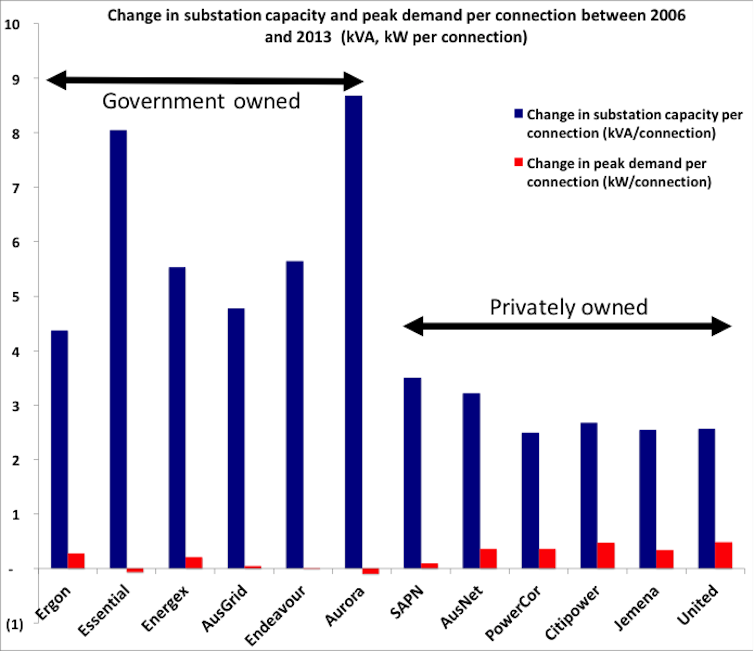

We also know that the distributors’ spending on substations far outstripped the increases in the peak demand on their networks. The figure below compares the change in the government and private distributors’ substation capacity (the blue bars) with demand (the red bars) over the period that most of the expenditure occurred. Again, the amounts have been normalised by number of customers.

The gap in spending between government and private distributors is stark. It is also obvious that in all cases, but particularly for the government distributors, the expansion of substation capacity greatly exceeded demand growth – which hardly changed over this period (and is even lower now, per connection).

To put it in more tangible terms, as an average across the industry, peak demand between 2006 to 2013 increased by the equivalent of the power used by one old-fashioned incandescent light bulb, per customer. But government distributors expanded their substation capacity by more than one 100 light bulbs, per customer.

The private distributors did relatively better, but still increased the capacity of their substations by the equivalent of about 30 light bulbs per customer.

My PhD thesis included econometric analysis that shows government ownership in Australia is associated with regulated asset values that are 56% higher than private distributors, and regulated revenues that are 24% higher, leaving all other factors the same.

To some, this evidence supports a “government bad, private good” conclusion. Indeed it was this line of argument that the Baird government in New South Wales used to justify its partial privatisation of two network service providers.

But in international comparisons of government and private distributors in the United States, Europe and New Zealand, no such stark differences are to be found. The huge disparity between government and private distributors is a peculiarly Australian phenomenon.

How we got here

This Australian exception originates in chronic policy and regulatory failure. As far back as 2011, the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) heard a proposal that government distributors should earn a return closer to their actual cost of financing – a suggestion that would have reduced prices significantly and removed the incentive to gold plate.

In response, the AEMC said the regulations were consistent with the “competitive neutrality” policy. But this is not true: in the policy’s own words, it was designed to stop government businesses from crowding out competitors. Distributors are protected monopolies; they do not have competitors.

The AEMC also argued, somewhat bizarrely, that it was good economics for a regulator to assume that government distributors are privately financed.

This represents the triumph of an idealistic “normative” regulatory model in which regulators act on the basis of how the regulated entity should behave rather than how they actually behave.

But it would wrong to blame the AEMC alone for this failure. All of Australia’s key institutions and governments have agreed that government distributors should be regulated as if they are privately financed. For governments that own their distributors, this has been a wonderfully profitable fiction.

Therein lies much of the explanation for what is effectively, if I may call a spade a spade, a racket.

It is an indictment of Australia’s polity and so many of its economists that the 2011 Garnaut Climate Change Review stands alone, in a library of reviews, as stating this problem clearly. In fact, if you review last week’s report from the ACCC, you will not find a single distinction between the impact of government and private distributors.

And if you thought this was yesterday’s war, you would be wrong. Despite the mass of evidence, our regulators persist in the fiction that ownership and regulation should be independent of one another.

It is difficult not to lapse into despair about Australia’s energy policy morass. Despite the valiant attempts by many, a deeply entrenched culture of half-truths, vested interests, ideology and wishful thinking still characterises all too much of what emanates from the political and administrative leadership of this industry.

Some energy consumers – Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull among them – will buy their way out of this problem through solar panels and batteries. But the poorest households and many business customers will increasingly be left carrying the can.

![]() Australians are angry about electricity. Not unreasonably.

Australians are angry about electricity. Not unreasonably.

Source: The Conversation. Reproduced with permission.