Last month, it was announced that Uber Technologies has a market valuation of $18.2 billion, roughly as much as Hertz and Avis car rental companies combined, slightly more than United Airlines. At $10 billion, Airbnb Inc, the home rental version of Uber, is worth more than Hyatt Hotels Corp. For many of us old timers, these valuations are hard to fathom.

What’s puzzling about the valuations of the newcomers is that they don’t yet generate much revenue, nor profits, yet are growing at gravity defying rates. CEO of Uber, Travis Kalanick, boasted in a recent interview that revenue is “at least” doubling every six months at the 5-yr old company.

The common feature of many of these new companies, aside from their rapid growth, is that they are disruptive, challenging and displacing the demand for services and/or products traditionally provided by the incumbent players. Uber, for example, competes against traditional regulated taxis, which have not changed their business model for decades. Uber’s smartphone app, which lets customers to hail cars driven by both professional and non-professional drivers, offers a cheaper, faster and more convenient way to get around town. Who wants to walk to and wait at a taxi stand when a cab can be waiting at the front door?

In an interview with The Wall Street Journal (7 June 2014) Kalanick said, “It’s not about the market that exists, it’s about the market we’re creating,” the kind of language one often hears in and around Silicon Valley these days. He, however, went on to say that Uber isn’t just competing against traditional taxis, but against private car ownership for urbanites. It’s about making “car ownership a thing of the past,” Mr. Kalanick said. Toyota and GM take note.

In an interview with The Wall Street Journal (7 June 2014) Kalanick said, “It’s not about the market that exists, it’s about the market we’re creating,” the kind of language one often hears in and around Silicon Valley these days. He, however, went on to say that Uber isn’t just competing against traditional taxis, but against private car ownership for urbanites. It’s about making “car ownership a thing of the past,” Mr. Kalanick said. Toyota and GM take note.

His vision is not as farfetched as you may think,

especially in the context of the shared economy, where private ownership of bikes, cars, lawnmowers, or even homes is radically and rapidly changing. Who needs to own a bike in Paris, London or New York when you can simply rent by the hour? Ditto for cars, as Mr. Kalanick would like it.

In congested cities, where parking is scarce and expensive, car ownership is indeed problematic. Besides, car owners have to pay for insurance, repairs and maintenance, license fees plus the costs of buying the car in the first place.

In congested cities, where parking is scarce and expensive, car ownership is indeed problematic. Besides, car owners have to pay for insurance, repairs and maintenance, license fees plus the costs of buying the car in the first place.

If Uber has its way, many urbanites will abandon their cars in favor of hourly car rental option such as Zip Car, or fast and convenient mobility offered by the likes of Uber. Traditional taxi and car rental companies can complain all they want, or try to get the regulators to protect their turf for a little while longer, a tactic they employed in Vancouver to block Uber.

Such tactics, however, provide temporary relief, like an aspirin. The headache goes away for a while, without addressing the underlying problem. Eventually the disruptive technologies will prevail because their value proposition is compelling. In the same vein, Airbnb is taking business away from traditional hotels, especially in the lower to mid-price range. It reportedly has more rooms to rent than traditional hotel chains in many markets, and at a considerable savings.

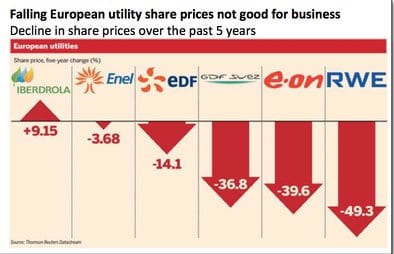

Why dwell on Uber and Airbnb in an energy newsletter? Because similar developments are disrupting traditional players and challenging their livelihood in the energy sector. Thermal generators in many mature economies are losing market share and market value (graph on page 15 and below) with the rapid penetration of renewables, fortified by financial subsidies and/or regulatory mandates.

Why dwell on Uber and Airbnb in an energy newsletter? Because similar developments are disrupting traditional players and challenging their livelihood in the energy sector. Thermal generators in many mature economies are losing market share and market value (graph on page 15 and below) with the rapid penetration of renewables, fortified by financial subsidies and/or regulatory mandates.

More recently, solar PVs have emerged as a serious source of revenue erosion for traditional utilities. As increasing numbers of customers produce more of what they consume, becoming prosumers in the process, they buy less from the incumbents, forcing the rates to rise even further for the remaining customers.

Just as taxi companies and traditional hoteliers are complaining to regulators and the city hall about Uber and Airbnb, thermal generators are complaining to regulators and policy makers to reduce or eliminate renewable subsidies and/or to introduce capacity payment mechanisms to reward them for keeping viable generation on the network for grid stability and reliability reasons – and to keep the owners solvent. Likewise, regulated utilities in a number of states and countries have pleaded for reductions or elimination of net energy metering (NEM) laws or feed-in-tariffs (FiTs), which eat into their revenues, and livelihood.

But just as taxis and hoteliers are unlikely to squash the rapid rise of the likes of Uber and Airbnb, proposed regulatory fixes in the power sector can only go so far. They are unlikely to address the fundamental underlying drivers of change leading to revenue insufficiency, only act as temporary band aid.

But just as taxis and hoteliers are unlikely to squash the rapid rise of the likes of Uber and Airbnb, proposed regulatory fixes in the power sector can only go so far. They are unlikely to address the fundamental underlying drivers of change leading to revenue insufficiency, only act as temporary band aid.

Take the current plight of thermal generators in many parts of Europe and, to a lesser degree, the US, who are suffering from depressed wholesale prices as a result of the abundance of renewable generation and the virtual disappearance of mid-day peak demand due to the rapid rise of solar PVs.

Reducing or eliminating renewable mandatory targets and/or subsidies is not much of an option – either because the train has already left the station or because the policy makers do not wish to scale back on the targets. Neither Germany nor California, for example are likely to withdraw their support for renewables for political reasons. Germany’s decision to phase out its nuclear fleet by 2022 and California’s goal to meet the states’ climate bill by 2020 makes renewables necessary (graph on page 3).

What about capacity payment schemes, now in vogue across Europe? It may help incumbent generators just enough so they will not mothball plants – but not necessarily make them profitable.

Likewise, utilities who are in favor of modifications in existing net energy metering laws or FiTs, are likely to confront the fury of a vocal public and their supporters who favor more self-generation, and more solar PVs, not less. The same applies to energy efficiency investments that also reduce demand. It would be political suicide to go against such popular measures, weather you are a utility CEO, a regulator or a savvy politician.

The incumbents’ revenue insufficiency, to coin a new term, must ultimately be addressed in the context of paradigm change brought about by disruptive technologies. An upscale hotel with valet parking, business center, concierge service, well-equipped gym, heated swimming pool and a gourmet restaurant may not feel threatened by the rise of Airbnb. But budget and mid-price range hotels are. What are the analogies in the energy space?

Perry Sioshansi is president of Menlo Energy Economics, a consultancy based in San Francisco, CA and editor/publisher of EEnergy Informer, a monthly newsletter with international circulation. He can be reached at [email protected]