South Australia’s remarkable transition to renewable energy has claimed new fossil fuel scalps, with Engie revealing this week it will shutter two diesel plants in the state years ahead of schedule, as solar, wind and battery storage have muscled them out of the market.

The French electricity giant said on Wednesday that it would close the 75 megawatt (MW) Port Lincoln plant and the 63MW Snuggery plant by July this year, ahead of full decommissioning by 2028.

The two power plants, used in times of peak demand and low supply, were supposed to last until 2030, but the pace of the transition to renewables – and tweaks to key energy market policies – have meant the generators are no longer financially viable to keep running.

The closures come after the Port Lincoln plant lost a $9 million a year contract with state grid company ElectraNet and after changes to the federal government’s capacity incentive scheme meant legacy fossil fuel generators would no longer be propped up financially.

“In the absence of appropriate revenue streams that recognise the capacity value of such plant, Snuggery and Port Lincoln are no longer profitable,” Engie said in a statement.

ENGIE ANZ CEO Rik De Buyserie says the company has worked closely with authorities to explore all possible options to keep the two power plants operating.

“But the accelerated pace of the energy transition continues to place pressure on all our existing thermal assets, and closure is the most rational outcome under these conditions,” he said.

In South Australia, “these conditions” include an electricity mix that in just over 16 years has gone from less than 1 per cent renewables to an average of more than 70 per cent generated by wind and solar.

Engie’s other South Australian thermal power plants include the 510MW Pelican Point gas power station, the 157 MW Dry Creek gas peaking plant in Adelaide, and the 90MW Mintaro gas station.

The company says these are expected to stay open as scheduled, but this is by no means guaranteed.

South Australia, which is long since coal free, is expected to reach “net” 100 per cent renewables within four years, according to a stunning prediction made by transmission company ElectraNet in November last year – the first time South Australia’s break-neck trajectory has been formally acknowledged by such an authority.

Alongside South Australia’s wind power, large-scale solar and huge rooftop solar resource – which on numerous occasions has generated enough electricity to briefly meet all demand – the state’s growing grid-scale battery storage fleet is starting to fill the supply and grid-services gaps that have recently been the core business of diesel and gas peaker plants. And other gas plants will be next.

“I think most probably we are cannibalising our own business,” was how AGL Energy COO Markus Brokhof put it last year, in explanation of the gentailer’s decision to build a 250MW/250MWh big battery at the site of its Torrens Island gas plants in South Australia.

“But, you know, if we don’t cannibalise it then somebody else will … Because at the end of the day, batteries are also in competition with gas plants.”

AGL’s Torrens Island B combined cycle gas plant, is scheduled to exit the market in mid-2026 at 50 years of age. Based on steam turbine technology – cutting edge at the time it was built in the early 1980s – it is not so useful in a grid where flexibility is key – it takes around 16 hours to power up to full capacity from cold.

The other operational gas plant at Torrens, the more modern Barker Inlet Power Station, can power up in five minutes, and so still has plenty of life left in it – and plenty of as-yet unchallenged advantages over a one-hour battery like Torrens. But as bigger and longer duration batteries are planned and come online, gas plants like AGL’s BIPS will increasingly struggle to compete in their own core markets.

In May last year, AGL said Barker Inlet might run for around an hour-and-a-half at a time in the morning and evening demand peaks.

Fellow gentailer, EnergyAustralia, is also getting on board the battery train, with plans unveiled just last month to build a massive four-hour battery in South Australia, and have it in operation as early as 2026, as part of a plan to roll out large storage facilities next to its existing fossil fuel generators.

Other batteries being proposed or under construction in the state include the 220MWh battery proposed by Epic Energy near Mannum, and Danish giant Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners is progressing its plans for a 240MW, two hour (480MWh) battery at Summerfield, with construction to begin by 2025.

Meanwhile, the South Australia’s existing batteries, including Australia’s first ever grid-scale battery storage project, the Hornsdale Power Reserve, are already making life tough for gas generators in the state.

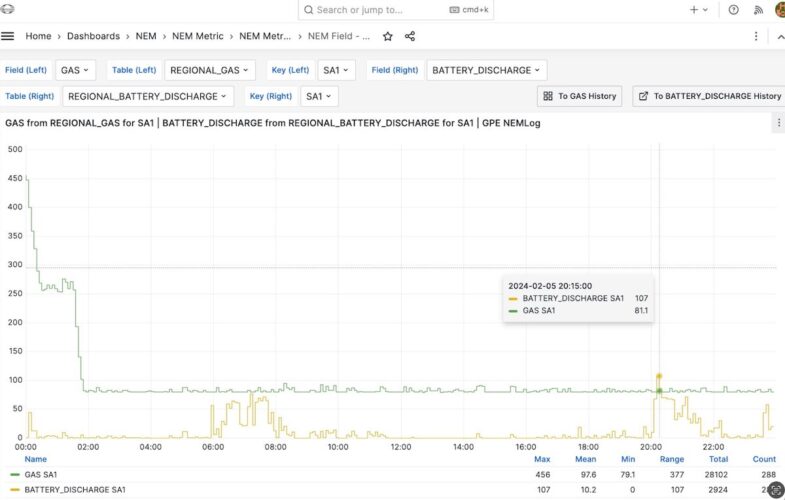

The charts below illustrate one of the instances where battery storage has delivered more to the grid than gas in South Australia. In this case, it was only for five minutes on Monday night, but it serves as a sign of things to come as more batteries come online.

The second chart shows the battery contributions in blue. The around 81MW of gas is there for system strength, but even that won’t be needed in future as batteries take centre stage for grid services, as well as for jumping into peak events.

Diesel generation, meanwhile, has always been a fairly niche – if lucrative – business. As UNSW energy market analyst Dylan McConnell explained here nearly two years ago, South Australia’s diesel peakers only come online “in those super peaks when prices go extremely high, maybe a couple hours a year.”

Clearly, that window of operation has got smaller – and less lucrative – since 2022.

A South Australia Labor government spokesperson told RenewEconomy on Wednesday that while the operation of Engie’s Snuggery and Port Lincoln diesel generators are “commercial matters for the company,” their early closure emphasises “the foolishness” of the previous Liberal government to privatise the state-owned generators, in place to provide 277MW of emergency reserve.

“Snuggery and Port Lincoln have been useful but their closure will come as the state’s fleet of generators increases with new projects coming on line,” the spokesperson said.

“Just yesterday, Neoen announced it had locked in finance for its Goyder South Stage 2 wind farm and the Blyth Battery which will have capacity of 238.5MW/477MWh, with a target to be in operation in 2025.

“The government is expediting approvals for several other grid-scale batteries which will provide energy at peak times.

“We are also working on the Renewable Energy Transformation Agreement with the Commonwealth to ensure reliability and facilitate more investment in renewables.”

Engie says the closure of the two diesel peakers will not lead to any job losses.