Does the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) claim that nuclear power is necessary for decarbonisation? No, but that has not stopped the Liberal-National Party (LNP) Coalition from claiming the IPCC tells them that to decrease emissions we must increase nuclear power.

The IPCC gathers scenarios and presents projections but in fact does not prescribe any one path to emissions reductions. All rhetoric about just following the science or any pretending that there is a linear relation from science to policy only serve to obscure the choices not being made transparent.

We should thus unpack the Coalition’s use of the IPCC and shine a light on some of the choices being made by banking on nuclear power for emissions reductions.

Energy policy on TV

On Sunday, host of ABC TV’s Insiders program, David Speers, interviewed Bridget McKenzie, the shadow transport minister for the Coalition, asking “is there anything you would do to bring down emissions in the next 10 years?”

“I’ll tell you what we are going to do to bring down emissions. We are going to do what the IPCC has said we should do to bring down emissions, and that’s increase nuclear power generation across the globe. We are hoping to open our first one in close to a decade, and in the meantime, we are going to bring on gas, a lower emissions fuel than coal,” McKenzie said.

Speers failed to interrogate this claim. The IPCC does not single out nuclear power as the kind of prime mitigation pathway that would warrant the Coalition to conclude that opting for nuclear power is what the IPCC says politicians “should” do.

Maybe impartiality as non-partisanship, balance or non-interference explains the lack of questioning, but journalism has for some time been more confrontational, with the credibility of the interview judged by the degree of probing questions.

Indeed the ABC editorial standards stipulate that “there are few things more important to factual content making at the ABC than the interview”, because interviews are where “we tease out matters of accuracy.” If the issue is “contentious or controversial”, then ABC general rules suggest “it is often necessary to take a ‘devil’s advocate’ approach” and ask the “awkward questions”.

Speers could have thus queried the robustness of McKenzie’s claim by asking whether the IPCC in fact claims nuclear power is necessary for decarbonisation? Or what degree of confidence the IPCC expresses in a nuclear pathway to emissions mitigation? Or does the IPCC in fact recommend nuclear power?

Unfortunately, absent further clarification, we are left alone to reconstruct the Coalition reasoning, and what follows is an attempt to do so.

The IPCC in 2018: presence but barriers

The Coalition claims their choice of nuclear power for emissions reduction is derived from what the IPCC says they should do. Yet in doing so the Coalition cherry-picks from the IPCC what features of the nuclear power option to emphasize. Specifically, raw presence over actual barriers.

To spot the Coalition choice to ignore barriers, return to the IPCC report titled Global Warming of 1.5°C from 2018. Four illustrative model pathways were provided. Each pathway represented different mitigation strategies for achieving net emissions reductions and limiting global warming below 1.5°C with little overshoot.

Each pathway projected nuclear power would increase its share of global energy. The four pathways were depicted in Figure SPM.3b from the Summary for Policymakers:

In the four pathways presented (P1, P2, P3, P4) more nuclear was projected, from +59% to +106% in 2030 and from +150% to +468% in 2050 (all compared to 2010). The nuclear industry responded by noting “all the IPCC scenarios require more nuclear power”.

More nuanced nuclear commentariat picked up on the IPCC report noting barriers to the uptake of nuclear power yet interpreted the barriers as signalling a “half full, not half empty” approach in which “getting serious about climate change … almost certainly involve[s] building significantly more nuclear power”.

Yet not everyone was happy with the barriers. A group of forty one ‘scientists and scholars on nuclear for climate change’ wrote an open letter to the Heads of Government of the G-20 nations, interpreting the IPCC listing of barriers to the uptake of nuclear power as amounting to fear mongering and misinformation.

Michael Shillenberger, famous for misrepresenting environmentalism in aid of promoting fossil fuels and nuclear power, bluntly dismissed the IPCC barriers as anti-nuclear polemic derived from manipulation and dishonesty.

What were those barriers? The full report is 630 pages long and you can access html view and pdf downloads of chapters here. But the barriers included the risks of weapons proliferation, ongoing obstacles to waste disposal, connections between nuclear installations and health hazards, compounding of water scarcity problems, high and/or uncertain costs, and deployment rate constrained by lack of social acceptability (see Chap. 4: p. 325 and Chap. 5: pp. 461-65).

When constructing “what the IPCC says we should do”, some nuclear critics interpreted the barriers as meaning we “should be following IPCC guidelines and heed the dangers of nuclear energy.”

The Coalition is thus not alone in directly mobilizing the IPCC to ground action. Yet there is still a difference. Critics emphasizing barriers to uptake to start a public discussion, but supporters emphasizing the raw presence of nuclear power in mitigation scenarios to avoid public discussion of barriers.

Did “all” scenarios in the 2018 report include nuclear? The IPCC write that “in some pathways both the absolute capacity and share of power from nuclear generators decrease (Table 2.15) . . . [because it is] constrained by societal preferences.”

How significant were the projected contributions to emissions reductions of nuclear and renewables? The nuclear share in global electricity generation was projected to be 10.91% by 2020, 14.34% by 2030 and 8.87% by 2050.

What was the projected share of renewables? “In 1.5°C pathways with no or limited overshoot, renewables are projected to supply 70–85% (interquartile range) of electricity in 2050 (high confidence)” (Summary for Policymakers).

The groundwork for “what the IPCC has said we should do” is thus contained in the response by pro-nuclear commentariat and nuclear industry sources to that 2018 IPCC report Global Warming of 1.5°C.

What is emphasized is that nuclear power is present in mitigation pathways. But what is deleted, rendering the Coalition invocation of the IPCC an instance of cherry-picking? Not all pathways include nuclear power. The barriers to uptake of nuclear power are sidelined from being transparently available for public consideration. The nuclear share of global electricity generation remains small, compared to a very large role for renewables.

The IPCC in 2022: nuclear is a tiny sliver in the pathways

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of 2022 is an overview of causes (Working Group I), consequences (Working Group II) and solutions (Working Group III) to global warming.

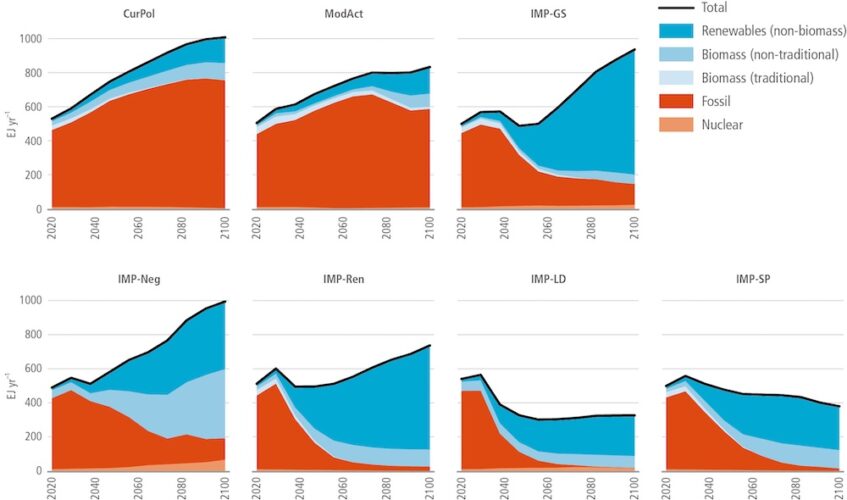

The IPCC WG3 report on ‘Mitigation of Climate Change’ discusses ‘illustrative pathways’ for how societies could evolve toward low-carbon futures. In Fig. 3.8 we see the seven illustrative pathways (see Section 3.2.5 ‘Illustrative Mitigation Pathways’ (the narratives are explained in full in Annex III.II.2.4)):

Nuclear power is light peach, and it is present in all seven pathways. Non-biomass renewables is the darkest shade of blue and is also present in all seven pathways. Again, we see that for the Coalition logic to carry any weight, “do what the IPCC has said we should do” must only mean that nuclear power is present in the IMPs.

Again, we are faced with having to disentangle the hidden choices that explain why presence-alone is sufficient for interpreting ‘what the IPCC has said’ as ‘go nuclear’.

If we set aside IMP-CurPol and IMP-ModAct, as they are high emissions pathways, it is possible the Coalition views the Paris Agreement as disposable. The remaining five pathways are presented as “consistent with meeting the long-term temperature goals of the Paris Agreement.”

Yet the Coalition has vacillated over whether it remains committed to the Paris Agreement, signalling an intent to breach the spirit of the agreement and leaving the door open to withdrawing. Maybe the pace of change and subsequent influence on emissions reduction by 2050 might be sacrificial lambs to the promise of nuclear reactors?

For instance, in the 2022 WG3 report, scenarios are divided into eight climate categories (C1 to C8). C1 is the most ambitious category (having a >50% chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C in 2100 with limited or no overshoot).

Only IMP-Ren, IMP-LD and IMP-SP fall into the C1 category. Given that renewables are doing the heavy lifting phasing out fossil fuels and lowering emissions, in Ren, LD and SP, why not interpret the IPCC as saying ‘go renewables’?

Most likely, because emissions reduction is not the point (for the Coalition)? Delaying decarbonization is the point. While the presence of nuclear power in the IMPs is emphasized, what is de-emphasized is the way IPCC IMPs model scenarios in which renewables expand vastly faster than nuclear power.

Below is a graph from Carbon Brief, in which key scenario characteristics from Table 3.6 in Chap.3 of WG3 (p. 353) are adapted: “increase in primary energy supply from nuclear, biomass and other renewables, % above 2019 levels by 2030 and 2050, in 1.5C scenarios with ‘no or limited overshoot’. Dots show the median value across relevant scenarios and bars show the 25th to 75th percentile range.”

Let’s have a conversation

Like what we saw in the pro-nuclear response to the IPCC Global Warming of 1.5°C report of 2018, the mere presence of nuclear power in IPCC WG3 mitigation scenarios and pathways in the 2022 report is made to carry the burden of implying the IPCC recommends nuclear power as a plausible route to ambitious emissions reductions.

The effect is to hide the choices the Coalition is making. For example, in the IPCC AR6 of 2022 the opening Summary for Policymakers only mentions nuclear power on p. 26 (C.3.6), where avoiding high capital cost technologies like nuclear power reduces challenges. The Coalition wishes to keep those challenges out of public discussion, despite rhetoric about “let’s have the conversation”.

The IPCC discusses those challenges, which replicate the barriers earlier mentioned:

“Nuclear power can deliver low-carbon energy at scale (high confidence). Doing so will require improvements in managing construction of reactor designs that hold the promise of lower costs and broader use (medium confidence).

“At the same time, nuclear power continues to be affected by cost overruns, high upfront investment needs, challenges with final disposal of radioactive waste, and varying public acceptance and political support levels (high confidence).”

On the one hand, it is simply a mistake to interpret IPCC scenarios and illustrative pathways as recommending or implying the necessity or even high plausibility of nuclear power as a front line emissions mitigation option. If there were a lesson to be drawn from the IPCC reports, it is that renewables are projected to play that front line emissions reduction role.

But set aside any prosecuting of which technological option the IPCC work paints in the best light. Relying on mere presence in IPCC scenarios and pathways to ground “what the IPCC has said we should do” is ultimately a tactic to avoid public discussion about the challenges with and barriers to deploying nuclear power in any quest to decarbonise.

Darrin Durant is Associate Professor in Science & Technology Studies at the University of Melbourne