For Australia, Asia, and particularly China is the primary source of our export revenue. The following chart clearly shows how iron ore and mettalurgical coal exports took off in the late 2000s as China pursued its rapid urbanization and its enormous construction boom.

Equally, even though thermal coal exports show signs of pausing, it’s still a $60 billion a year business that Australia will need to replace over the coming decade.

Figure 1: Resources exports. Source: Office of Chief economist

Japan is in the G7 and just agreed to phase out coal

Although Japan is likely to be the last to achieve the goal the latest G7 Meeting in Italy has agreed to phase out coal generation by 2035, or in Japan’s case at some unspecified date. I interpret that with optimism, as the expectation for Japan too to do its bit has clearly increased and been acknowledged.

If Japan does adopt this stance it is signifiant for Australia. It presently exports around 70 million tonne a year of thermal coal to Japan and that market will disappear.

- Japan will have to replace that generation, and other countries in Asia will pay attention.

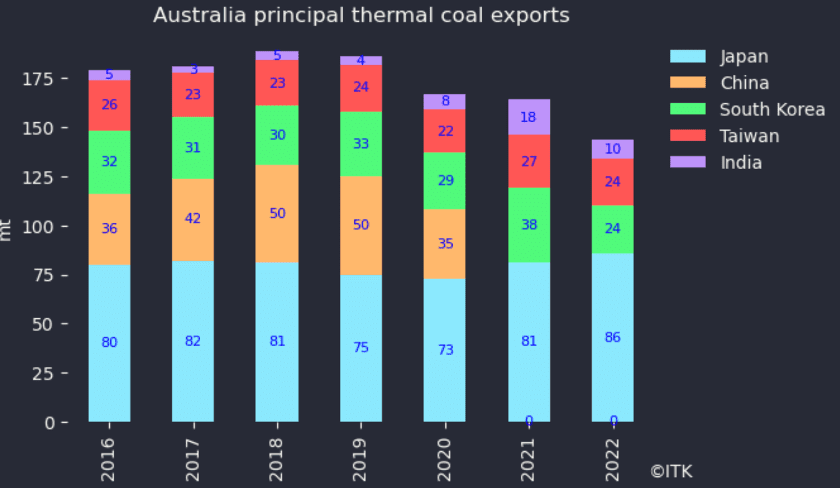

Australia’s thermal coal exports to Asia are shown below. Regretably, reliable figures from the Australian Government for calendar 2023 are not yet published.

As of early 2024 exports to China are larger than those to Japan. Broadly speaking about 150 mt of thermal coal goes to Asia worth @ A$120/t or around A$18 billion a year.

Arguably, Vietnam should be on the chart, but it’s not included in the Resources and Energy Quarterly published by the “Chief Economist office”. Frankly, the office could get its act together on the numbers a bit quicker.

Figure 2: Australia thermal coal exports. Source: Aust Govt

In my view Australia currently has no bankable replacement for those exports. Nevertheless at a minimum it should be obvious, but won’t be, even to the coal producers that this is no longer a growth market and, in my view, one that is going away quicker than would have been thought possible even 5 years ago.

This then leads to the question of how Asia, and particularly in this case the Asean nations are going to get electricity, and perhaps the resulting cost.

Renewable energy and Asean

The following section is basically information extracted from a recent DNV report ” ASEAN interconnector study ” which looked at the benefits of connecting the ASEAN nations more deeply from an electricity point of view. I found the information presented in this study of great interest, revealing how little I knew about Australia’s neighbours.

Figure 3: ASEAN. Source:DNV

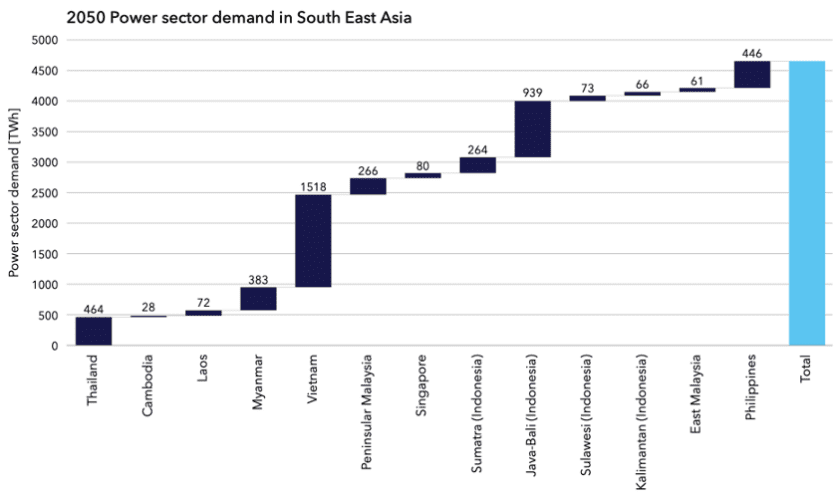

The surprise, to me, in electricity consumption, and this chart is for 2050, is Myanmar, which is comparable to Thailand. For Asean overall 4.5 PWh in 2050 compares with 2023 China consumption of 8 PWh.

Although the forecast will be wrong it’s yet another reminder of, depending on your personality, the opportunity or the challenge. From today’s perspective there is still almost unbounded growth ahead for renewable energy. The opportunity is large.

Figure 4: Consumption 2050 forecast. Source:DNV

The next point was to note how low the expected onshore wind capacity factors are in Indonesia, Myanmar and to a lesser extent even Thailand. And that, as presented, the solar factors are also no better than rooftop results in Australia.

An apparent limitation of the DNV study is that solar capacity factors appear to have been calculated for fixed ground mounted solar on a DC basis. That is quite different to how it’s done in many places.

Figure 5: Capacity factors used for modelling. Source:DNV

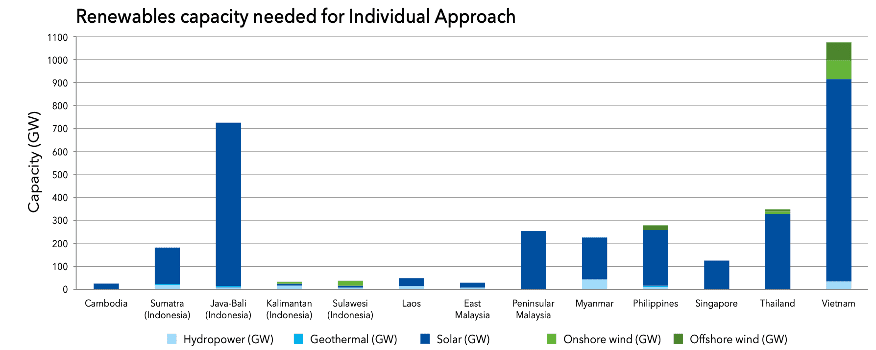

Using those capacity factors results in the following solar and wind capacity required for each country to decarbonise before considering the region as a portfolio and then the required transmission.

Figure 6: Capacity required to decarbonise. Source:DNV

To this must of cousre be added storage, transmission and hydrogen. DNV estimated the total cost at somewhere in the US$6-8 trillion level, which seems high to me. However Figure 6 also broadly illustrates that Vietnam and Bali have potentially big roles to play.

Limited interconnection at present

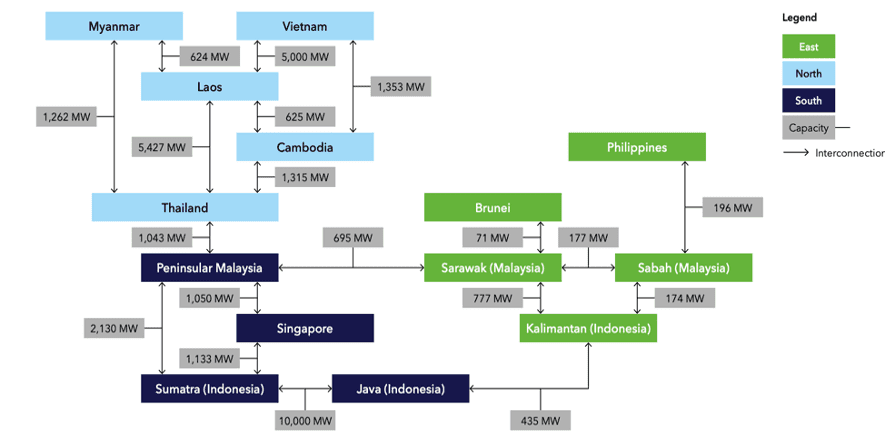

The ASEAN interconnection grid has been a concept since 1997 and has a conceptually supported study known as the Asean Interconnection Masterplan Study (AIMS). Three such studies have been done, in 2003, in 2010 and in 2021.

As is usual with transmission the benefits are:

- Economic (a portfolio impact);

- Security (insurance);

- Facilitates decarbonisation.

The latest version of the AIMS plan appears to envisage links between countries typically round the 1 GW level:

Figure 7: target case transmission. Source: DNV

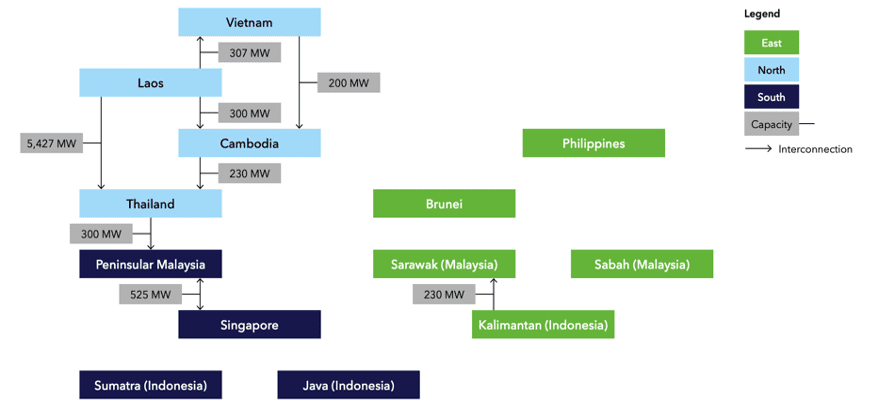

The modelled outcomes compare with the very limited existing transmission links other than between Laos and Thailand.

Figure 8: Existing interconnectors. Source:DNV

DNV max transmission case seems aggressive

It’s great to read the results of the DNV study which suggests that up to US$1 trillion can be saved on the decarbonisation journey by building stronger interconnectors, but I must say I raised my eyebrows when I saw interconnectors as big as 286 GW in the modelled solution.

A solution which also required considerable hydrogen flow. Outside of China, as far as I know transmission capacity greater than 10 GW on any single route is quite low.

China’s largest single line under construction is the astonishing 1600 km, 800 KVA Ningxia-Hunan link. By my often faulty arithmetic that’s an 8GW link capable of shifting 40 TWh (20% of NEM wide consumption).