Newly sworn-in minister for climate change and energy, Chris Bowen, says the new Labor government wants to avoid opening new fronts in the ‘climate wars’, saying he intends to implement new policies while avoiding potentially messy and protracted negotiations in parliament.

Commenting ahead of his appointment as the energy and climate minister, Bowen said that Labor’s climate policies would need minimal legislative changes.

Labor plans to adapt the existing Safeguard Mechanism – established by the Coalition – to impose stricter caps on industrial emitters and will rely on its ambitious ‘Rewiring the Nation’ plan to invest up to $20 billion in new transmission infrastructure to unlock new wind and solar projects.

It means Labor could avoid the need to pass a major piece of climate policy reform – like the introduction of a new emissions trading scheme – limiting the opportunities for the crossbench to pressure Labor to go further.

Bowen said this approach would allow the new government to avoid a new front in the ‘climate wars’.

“We designed that very deliberately so that we would have scope to just get on with the policy and not get bogged down in the climate wars,” Bowen told the Sydney Morning Herald.

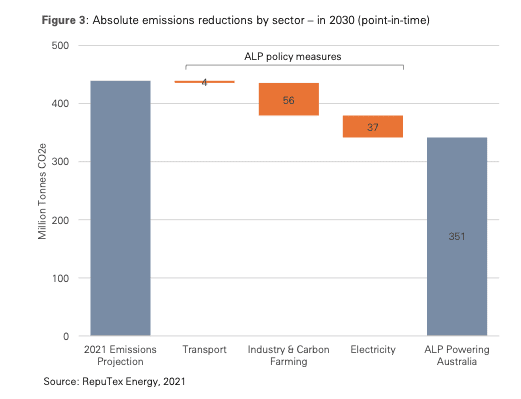

Modelling commissioned by Labor before the election, and completed by Reputex, suggests that the Rewiring the Nation plan could support the market share of renewable electricity to grow as high as 82 per cent by 2030.

Combined with a strengthened Safeguard Mechanism, Labor could deliver the bulk of the emissions cuts needed to achieve its 43 per cent reduction target by 2030 while avoiding the need for substantive legislative reform.

Before the election, Labor ruled out making deals with the Greens or independent crossbenchers on climate policy – saying that while it would welcome support to implement Labor’s policies, it would move forward alone if support was lacking.

Bowen said it was Labor’s preference to legislate its climate change commitments, including enshrining a net zero emissions target into law but would not seek to compromise on the level of the targets or their timelines.

“Other countries have legislated; we think that’s the best practice. As I’ve said publicly, if the parliament doesn’t want to legislate a 43 per cent target, we’ll do it without legislation,” Bowen said while unveiling Labor’s climate policy package last year.

“So we’re not going to see it torn apart by the parliament. We will proceed without the legislation if it becomes political.”

Read more: Chris Bowen confirmed as new energy and climate minister, McAllister as assistant

While Labor may be able to resist calls to increase the level of Labor’s 2030 emissions reduction target, Australia will need to communicate its 2035 emissions target during the current term of parliament.

The Paris Agreement rules require countries to set five-yearly targets at least 10 years ahead of time – each target ‘ratcheting’ higher than the previous one – meaning Bowen will have to grapple with the question of stronger targets at some point in the next three years.

The Greens are calling for Australia to reach net zero emissions by 2035, and the ‘teals’ are seeking 2030 targets of between 50 and 60 per cent. All have indicated that they would use any leverage in parliament to push for stronger targets.

This week, Bandt pointed to the abandoned demerger plans of AGL Energy as underscoring the need for the federal government to play a greater hands-on role in managing the retirements of coal fired generators, including the need to stop the development of new fossil fuel projects.

“Instead of leaving these decisions to corporate boardrooms, Labor needs to update its climate legislation to include a regulated timetable of power station closures by 2030,” Bandt said.

“Given the urgency of the climate crisis and the need to support workers and communities through the transition, a legislated timetable of closures makes sense.”

In a sense, Bandt is right – the current turmoil in the electricity market will likely require greater direct engagement by the federal government than had been shown by the former Coalition government.

Labor inherits an energy market with wholesale electricity prices at all-time highs, a growing number of electricity retailers going under, and major energy market players battling with significant uncertainty around their future.

Since Labor’s election win, AGL Energy has abandoned plans to split the company into two and Origin Energy has withdrawn its earnings guidance after being slammed by surging coal prices.

Bandt called on Bowen not to adopt a ‘take it or leave it’ approach to climate policy.

“Labor should not let their idea of the perfect be the enemy of the good. Labor’s vote has just gone backwards and the public clearly wants the Greens and others to have a say,” Bandt said.

“The public has just rejected this kind of hairy-chested ‘my way or the highway’ approach to climate that Labor is now taking. People want us to work together and the Greens are up for discussions about getting good climate laws passed, but it seems Labor isn’t.”

Of course, Bowen does have an alternative path to passing legislation – negotiating with the Coalition opposition.

It is not yet clear who will take on the shadow energy and climate ministries – Angus Taylor is expected to be elevated into a higher-profile role, and his expected successor, Tim Wilson, lost his seat in parliament.

New opposition leader Peter Dutton’s track-record on climate change doesn’t imbue much confidence of a newfound embrace by the Coalition for stronger climate action, but new Nationals leader David Littleproud says he accepts Australia must move towards a zero net emissions target.