Mining giant Rio Tinto says it has signed contracts for what will be the biggest wind and solar farms in Australia, but the future of the biggest manufacturing assets in the country remain in the hands of the state and federal governments.

Rio Tinto CE Jakob Stausholm told investors on the company’s earnings call last night (Wednesday night Australia time) that the company needs to secure competitive low carbon “firming” power to support its big investments in wind and solar, and make its smelters and refineries competitive in the international market.

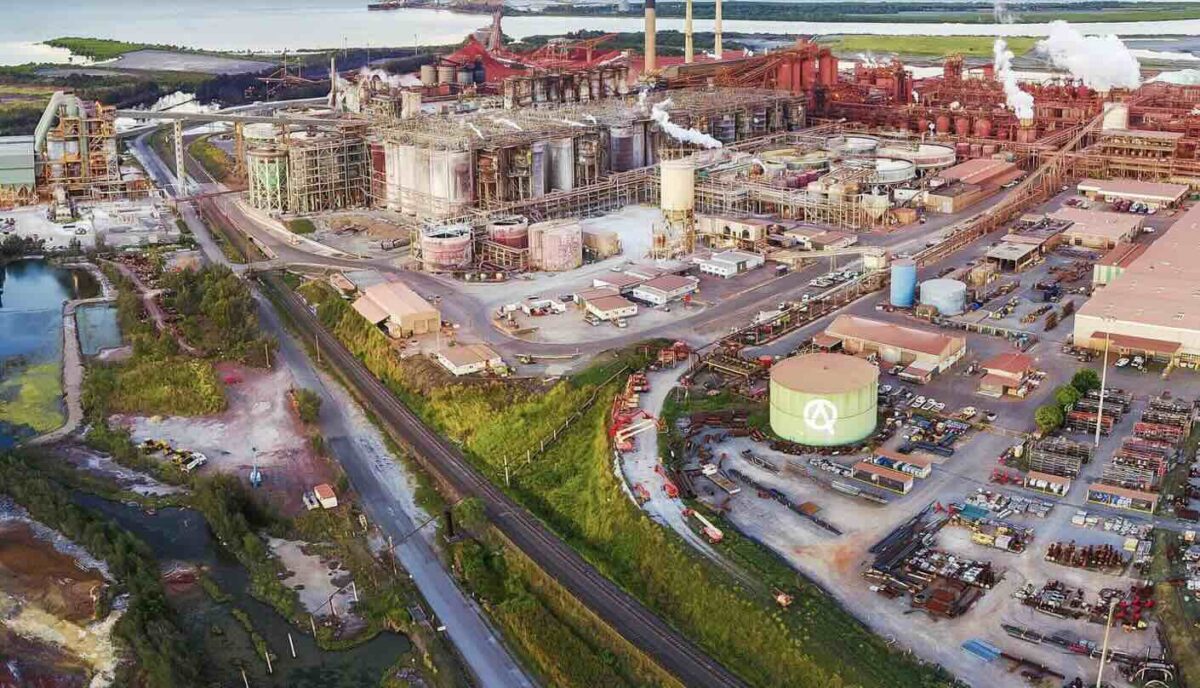

The three big smelters and refineries in Queensland are currently powered by coal, but this is no longer tenable in an international market focused on low, or zero carbon products, so Rio Tinto is trying to secure reliable, low carbon solution by the end of the decade.

“We’ve done two things so far. We are building the biggest solar farm in Australia and we are with building the biggest wind farm,” Stausholm said, in reference to its deal with the 1.1 GW Upper Calliope solar project announced in January, and the 1.4 GW Bungaban wind project on Wednesday.

“But ultimately the next step has to come from the Queensland Government and the Commonwealth, namely to offer competitively priced firming power,” he said.

“And if we can’t get that to work then we don’t have long term solutions for our Pacific aluminium business (which includes the Boyne Island smelter, and the Yarwun and Queensland alumina refineries).

“We want to protect the Australian business, but we have to bear in mind that it is not an Australian business. It’s an export business that competes with our aluminium in Canada that competes.

“It’s an export business that competes with our aluminium in Canada that competes with aluminium from the Middle East everywhere.

“So we need to make sure that it becomes competitive. But it is also probably the biggest manufacturing assets remaining in Australia. So … I would argue (that as) we are in the same boat (as the government) we should be interested in finding a viable pathway forward for those assets.”

Rio Tinto has said that it will need around 1 GW of dispatchable capacity to power its refineries, and so far has locked in more than 2.2 GW (its share of the output of the two wind and solar assets).

It could boost that solar and wind capacity to up to 4 GW, but its clear preference is to lock in some dispatchable capacity, be it in the form of battery storage, peaking gas plants, or existing infrastructure.

It is looking for government support on this component, because while wind and solar is relatively low cost, dispatchable capacity is less so.

“Renewable energies are less stable and more complex to firm up,” Stausholm said in response to a later question, adding that batteries and gas peaking plants, and other existing infrastructure on the grid could provide the capacity.

“Firming is access to the grid, it is not our firming, but the Queensland government firming. I want to know how I can competitively priced firm power with the lowest possible carbon footprint.”

RenewEconomy asked Rio Tinto exactly what it expected the governments to do, and if it was looking for pricing support or some other guarantees for firm power, or simply clarity on policies such as the Capacity Investment Scheme. It did not hear back in time for publication, but we will update the story if we do hear back.

Meanwhile, the Tomago smelter in NSW – majority owned by Rio Tinto – is also seeking a similar amount of renewables and dispatchable generation, and has contracted Energetics to help manage that process.

Rio Tinto also plans to build, or contract, some 1 GW of renewable and storage capacity in the Pilbara to support its iron ore operations in that region.

It has so far outlined $600 million of planned investments, including 230MW of solar power facilities (over two 100 MW plants, one of which is under construction, and one 30 MW plant, and 200MWh of storage. This is in addition to the 34MW solar facility already installed at Gudai-Darri.

It has also developed partnerships with Scania, Caterpillar, Volvo and Komatsu to deploy more efficient autonomous haulage solutions and battery-powered trucks, but says the switch to electric transport is unlikely to happen at great scale before 2030.

This is contrast to the assessment of rival iron ore miner Fortescue Metals, which aims to be at “real zero” emissions, meaning no burning of fossil fuels, by the end of the decade.