Australia’s biggest climate polluters could be set emission reduction targets of up to six per cent a year under a Labor proposal to try and transform the much maligned Safeguard Mechanism into something useful.

The Safeguard Mechanism was part of a package brought in by former prime minister Tony Abbott in the place of the carbon price he destroyed. It was derided as a “fig leaf” of a carbon policy by his Coalition rival Malcolm Turnbull, and by Labor, but is now likely to become a centrepiece of the country’s climate policy.

It impacts 215 big polluters that generate more than 100,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent a year, and includes power companies, airlines, coal mines, smelters, cement producers and other big manufacturers.\

Existing facilities have been governed by a “baseline” scheme that has often been conveniently lifted to allow even more climate pollution as they “expand” their business, but Labor says it now wants to add real bite to the mechanism, and turn it into an effective emission reductions tool, and too allow more carbon trades.

The key in how this turns out – after detailed consultations with industry – will be how the baselines are set, what the targets will be, and what might be available for companies to “trade” their way out of their emissions debt with carbon credits. It seems international credits, at least for the time being, are being ruled out.

It could also become a battle ground with The Greens, crucial for approval in the Senate, over how new facilities are treated and the impact of new coal and gas projects.

“The 114 new coal and gas projects in the investment pipeline will blow even the government’s weak climate targets, so how the Safeguard Mechanism deals with new coal and gas is critical,” Greens leader Adam Bandt said in a statement.

The discussion paper released by climate and energy minister Chris Bowen on Thursday says Labor has not yet settled on an annual emissions reduction target for the big emitters – it could be 3.5 per cent to six per cent – as that will depend on other related policy settings.

These include questions about how much of the country’s soon-to-be-legislated 43 per cent emissions reduction target by 2030 should be met by the big emitters themselves.

They also include questions about what protections will be in place for trade exposed industries, the nature and use of carbon credits – which are under intense scrutiny over their climate integrity – and even if the emitters should get government funding to help pay for their emissions cuts.

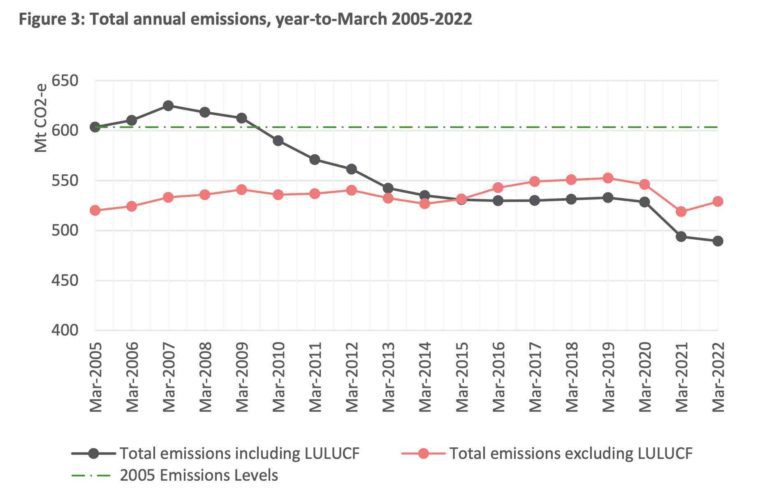

Australia has claimed that it is well on the way to meeting its Paris climate commitments because of big falls in emissions since 2005, but the grim reality is that industrial emissions have barely moved in the past two decades.

This is despite significant cuts from renewables in the electricity sector, which have been largely offset by the emissions created in sending fossil fuels overseas. And while many businesses say they have factored emissions reductions into their business plans, precious few have actually done anything about it.

Australia’s claimed emissions reductions are the result of the highly controversial land use assessment, and analysts such as NDevr note that on current projections, Australia is way off track to meet its newly raised Paris commitments, even including land use.

Hence the need to actually Do Something.

“A revamped safeguard mechanism will help Australian industry cut emissions and remain competitive in a decarbonising global economy,” Bowen says in a statement.

“We are building on the existing architecture of the safeguard mechanism but getting the settings right to get emissions heading downwards while supporting industry competitiveness.”

Bowen wants the new Safeguard Mechanism to be in place by July next year, and although a draft proposal is expected by December, there is still clearly a lot to figure out in exactly what they are aiming to do, and how they will do it.

The paper canvasses five key questions and is seeking feedback from business (most business groups are in favour of the general idea, but the devil will of course be in the details).

These main questions are around the setting of baselines for existing and new facilities; the indicative rates of baseline decline, the use of offsets and credits, treatment of trade exposed industries, and consideration of existing and new technologies, which may influence the speed of emissions baseline declines in certain sectors.

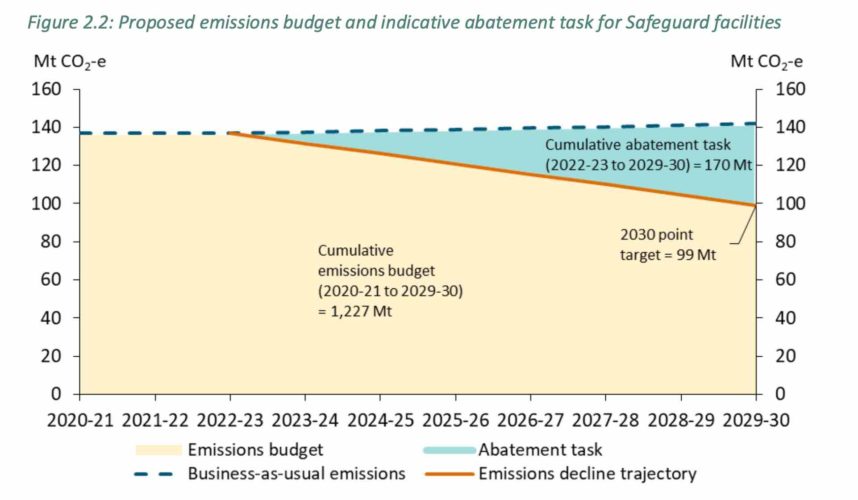

The paper says the cumulative abatement task for the biggest polluters will be around 170 million tonnes to 2030, although this could grow to 230 million tonnes if business as usual growth was higher than expected.

The paper says the headroom has to go. Firstly, because if it was retained, it would mean facilities would have to cut emissions at a much faster rate from 2025/26, and those facilities without headroom might feel they have been unfairly treated.

“Legacy baseline setting arrangements mean that, in aggregate, current baselines are well above emissions,” the paper says.

“In 2020-21, aggregate baselines were 180 Mt CO2-e, compared with covered emissions of 137 Mt CO2-e. This 43 Mt gap—referred to as ‘headroom’—is distributed unevenly across facilities, and has two consequences.”

It puts the blame for this on previous decisions by the then Coalition government. “Much of the headroom is a legacy of the initial allocation process, which fixed baselines at the high point of emissions over three years, and/or the significant optionality in baseline setting arrangements that followed.”

The removal of the headroom means that companies that do better than their baselines will get “credits” they they can then trade with others. The paper says these credits will not have the same integrity questions as the carbon offsets that are currently under review from former chief scientist Ian Chubb.

Companies that exceed their baselines may still be able to buy carbon offsets, known as ACCUs – subject to that review, but there are questions to be resolved about “double counting.”

There is also concern about a push to set “sector average” baselines, which Reputex – which modelled Labor’s climate policy – warns could lead to some poorly performing facilities getting credits even though they have undertaken no additional action to reduce their emissions.

The paper also makes it clear that international offsets are not favoured, and won’t be used – at least initially.

“We would only consider international offsets in the Safeguard Mechanism if the units are of high integrity and the mitigation outcome can be formally transferred to count towards Australia’s Paris Agreement commitments,” it says.

“Limits on the use of such international offsets may also be appropriate, so they do not become a mechanism to avoid transforming our domestic economy.”

The paper also talks about “tailored treatment” for trade exposed industries. Proposals include funding for new low emission technologies, issuing credits to help meet the costs, and differentiated baseline decline rates.

It also canvasses methods to deal with industries on the cusp of embracing new technologies, but not within a certain time frame. It discussed measures on how a lower decline in emissions in early years could be allowed to be offset by higher declines in later years once the technologies are available.