Grid-scale battery storage is having a renewables moment in Australia, with huge opportunities to fill in a “50 gigawatt-hours a day” arbitrage opportunity to shift excess solar to the evening peak. The only question: Who will build them?

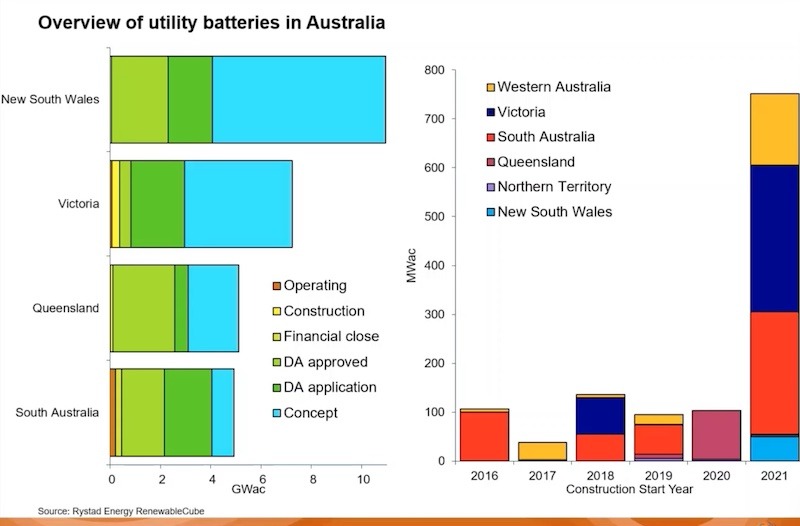

In a Rystad Energy webinar on Tuesday, senior renewables analyst David Dixon described 2021 as a “breakout year” for utility-scale batteries in Australia, with almost 1GW of new capacity built or in construction, including the now operational 300MW (450MWh) Victoria Big Battery – Australia’s biggest, so far.

On top of that, a development pipeline of 193 assets – or more than 28GW, and counting – has emerged over the year, in which Rystad counts projects spanning from the concept phase of development to assets that have completed their hold point testing.

And this number is growing on an almost daily basis, with French renewables developer Neoen on Wednesday revealing plans for another 300MW big battery in South Australia, just as its Victorian project kicks into gear.

“This pipeline of utility-scale batteries has grown from less than five gigawatts only a few years ago to over 28 gigawatts at the present time and does not include batteries associated with any of the export projects in the upper states,” said Dixon.

“This looks very reminiscent of what the utility PV and wind industry went through in 2017 in Australia, when it really took off and then sustained multi gigawatt installations in the years after that.”

Dixon noted that the large-scale battery sector had also seen an increase in the size of individual projects over the year, taking them from between 50-100MW, at the most, to two assets in 2021 greater than 200MW: AGL’s 250MW Torrens Island project in South Australia and the Victorian big battery.

On the economics side, Dixon said that frequency control ancillary services was currently “by far the biggest sector for revenue” for the existing batteries in operation in Australia, but that this market was considered relatively small.

Rystad believes the vast bulk of future profitability for grid-scale battery-storage projects would be on energy arbitrage, where storage of two hours and upwards would be key.

“We’re requiring more and more energy during that peak time during the evening,” said Dixon.

“While the NEM has had a lot of variable renewables coming to the system over the past four years, we’ve had a decline in dispatchable capacity.

“In 2011, that figure was 48GW. Today, it’s 44GW, and next year it will be 42GW as the Liddell coal fired power station exits the grid, and that will put further upward pressure on the New South Wales spread, in particular.

“Batteries, at the moment, are largely being used for frequency control ancillary services, but there’s a 50 gigawatt-hour per day evening opportunity for batteries to really come in and add supply.”

But Dixon said questions remained around who would bankroll the tens of gigawatt-hours of battery storage needed for energy arbitrage, with costs still relatively high and investors in Australia still wary of risks around policy and revenue.

According to Rystad, the levelised cost of storage for utility batteries in Australia, using the example of a 250MW project, was at between $A200 to $A300 per megawatt-hour. But that the fixed cost components of the equation “really come down” on a per kilowatt-hour basis.

“Once you get down to about two hours of storage, that’s really where you get the majority of the benefits of economies of scale before it really starts to level off,” Dixon said.

“There is an opportunity here for batteries to shift energy in the market, but just to highlight the key uncertainty facing developers … if you were to have installed a battery in Queensland you would have been very profitable this year, but last year, you would have… not made any money in the energy arbitrage space,” he said.

“And the question for banks is how do you lend against this given the uncertainty in your revenue and cash flow streams?… So then, the question is who, actually, is going to be building these batteries?”

On that front, Dixon said batteries used in off-grid applications such as to help power mining operations in remote Australian locations, would play a key role the battery cost learning curve – although at smaller scales.

On the grid-connected side, Australia’s big incumbent gen-tailers were expected to have a big hand in development, thanks to their big asset base to lend against and economies of scale.

“Whether that’s these companies doing it themselves, or whether they contract through a third party, that is a renewable developer, to build it for them and then they just get the benefits,” said Dixon.

“As an example, AGL have applied both methodologies … through Wandoan [in Queensland], but they’ve also had the Torrens Island big battery.”

See also RenewEconomy’s Big Battery Storage Map of Australia

Good, independent journalism takes time and money. But small independent media sites like RenewEconomy have been excluded from the millions of dollars being handed out to big media companies from the social media giants. To enable us to continue to hold governments and big business to account on climate and the renewable energy transition, and to help us highlight the extraordinary developments in technology and projects that are taking place, you can make a voluntary donation here to help ensure we can continue to offer the service free of charge and to as wide an audience as possible. Thank you for your support.