The US electricity system is undergoing the biggest change in its 130-year history. The scale of electricity generation is rapidly shrinking, from coal and nuclear power plants that can power a million homes to solar and wind power plants that power a few to a few hundred nearby homes.

Electricity demand has leveled off, so that every unit of new wind and solar power produced for the grid displaces a unit of fossil fuel energy. Batteries and electric vehicles provide new tools for distributed energy storage. Smartphones and smart appliances are giving electricity customers unprecedented opportunities to manage their energy use.

A growing number of experts in and out of the utility industry believe this shift in source and scale of power generation to distributed and renewable is largely inevitable. The technological change challenges us to redesign the electricity system.

Many are calling this potential adaptation “Utility 2.0” – a second generation electric company that can accommodate and thrive alongside distributed clean power generation, energy storage, and advanced energy management. Many utilities are fighting this transition, clinging to the inertia that has kept them in business for decades as sovereigns of the grid.

Up for grabs is $364 billion in annual electricity sales.

There’s an unprecedented opportunity to keep that money within communities. Already, half a million households in the US have on-site solar power plants, a quarter million have an electric vehicle, and 6 in 10 have a smartphone. The costs of local energy production and management are falling rapidly.

But history and regulatory and institutional inertia mean that most of the revenue in the electricity system continues to flow away from utility customers and their communities.

In “Utility 1.0,” both the technology of the original electricity system and its ownership were large and centralized. Vertically-integrated utility companies owned everything, from the power plant to the meter outside a home or business. In an era when cost-effective power generation came from coal or nuclear – with massive economies of scale – centralized ownership was the key to raising the capital for power generation. Utilities were rewarded with public monopolies and guaranteed rates of return to attract low-cost capital and drive down costs.

Source: Lawrence Berkeley Labs

Utility 1.0 is a business model for an electricity system entirely owned by the electric company, from power plant to transmission and distribution network to the meter on the building. The system is based on large power plants that capture the economies of scale in producing power from fossil and nuclear fuels.

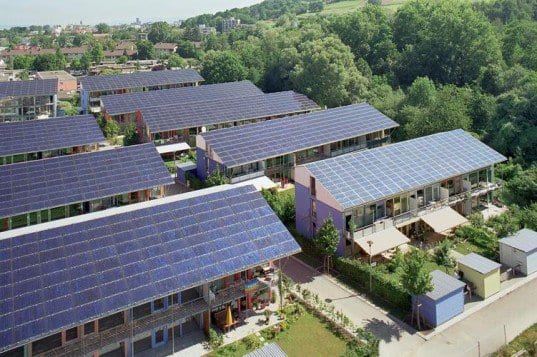

The new technologies of power generation no longer require the same scale or centralization of ownership. The shift toward decentralized power sources like solar is nearly inevitable as the cost of distributed renewable energy continues to fall, and for-profit (investor-owned) utilities in particular identify ways to profit from clean energy.

Utility 2.0 is an adaptation, a business model that allows utilities to accommodate the shift to new technologies and achieve a 21st century electricity system that is efficient, low-carbon, and flexible. Proponents envision a local electricity or distribution grid managed independently from the owners of power plants and other energy resources, creating a marketplace for utility and non‐utility participants to provide their services. It’s a bold and necessary step toward a business model that mirrors the changes in the scale and technology of electricity.

But Utility 2.0 will prove inadequate if it remains indifferent to the flow of energy dollars out of communities.

Local control and equitable access are the keys to unlocking an economic transformation that parallels the technological one, by allowing communities to maximize capture of their local energy dollar. It means an energy system that empowers electricity customers to manage their electricity use, produce power individually or collectively, and transact with their neighbors, local businesses, and their city. Consumers become, in Alvin Toffler’s elegant description “prosumers.” They can make the decision as to whether to consume, or produce, or store electricity at any given moment. Individuals and communities, formerly simply passive observers of utility-driven power generation, can become the agents of their own energy futures.

We might call this new electricity business model Utility 3.0, or as we do in this report, energy democracy. It’s as fundamental a change in the ownership of the energy economy as Utility 2.0 is a response to the change in the technology and scale of power generation.

Energy democracy seems daunting because it means confronting the economic and political might of (monopoly) incumbents. But it’s also enormously worthwhile, because in giving communities the opportunity to recapture billions of currently-exported energy dollars, it builds a self-‐interested political movement for accelerating the transformation to a low-carbon energy system: a climate necessity.

This report explores what’s brought us to this moment, the core principles and existing practice of Utility 2.0 and energy democracy, and key strategies to ensure that the transformation of the electricity system is both a technological marvel and an equitable economic engine.

Prelude to Utility 2.0

The Golden Age of the electricity system began in the mid twentieth century, the natural evolution of a model pioneered several decades earlier when Samuel Insull of Chicago’s Commonwealth Edison led a movement toward monopolies. A single, investor-owned company would generate, transmit and sell electricity to the final customer. In return for a monopoly, utilities would be subject to state regulation. States provided utilities with their costs plus a fair rate of return in exchange for reliable and universal service.

This formula was similarly used by rural electric cooperatives and municipal utilities, and it encouraged large investments to meet the needs of a growing population and even faster growing electricity demand.

Three waves of change have broken over the electricity industry, but none as transformative as today’s. The timeline below illustrates, in brief, the past 40 years of change, it is also described below.

The First Wave of Change

The quadrupling of oil prices in 1974 and again in 1979-80 ended the cozy and predictable golden age. The price of fossil fueled electricity soared while higher interest rates dramatically increased the cost of power plants. At the same time substantially higher prices led to a sudden slowing of per capita electricity consumption. Several utlities went bankrupt. Investors fled. A 1984 cover story in Business Week wondered, “Are Utilities Obsolete?”

State regulators responded with a new “least cost planning” approach that required utilities to consider cost effective energy efficiency improvements before building new power plants. It was only partially effective, failing to cultivate many energy efficiency investments that utilities could not make money on, but improving planning for new power plants. In an effort to reduce reliance on oil, the federal government enacted the 1978 Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA), which opened the electricity generation market to non-utility generators who used higher efficiency or renewable-fueled power plants.

The Second Wave of Change

By 1990, independent power producers (IPPs) were adding more new power plant capacity than traditional utilities and they lobbied for the freedom to sell power outside their local utility’s service area. In response to this aggressive campaign – led by Enron – Congress deregulated the wholesale market and made the electricity transmission grid a common carrier.

This deregulation led to an explosion in transmission line investment to meet the increasing, long-distance bulk transfer of power.7 The regulation of the new interstate market similarly grew, with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) implementing rules to overcome the conflict of interest between utilities that generated their own power, but that had to share their transmission lines with competitors. The rules were only marginally successful, until FERC insisted on greater structural separation by creating new entities to oversee transmission access and pricing.

Independent power producers also wanted competition at the meter, and lobbied states for permission to sell directly to final customers. About half of the states deregulated retail electricity sales, requiring many former monopoly utilities to divest some or all of their generating capacity and increasingly becoming distribution utilities. (Retail competition proved elusive, however, and California’s near-bankruptcy due to price manipulation by Enron and others led many states to freeze or reverse retail deregulation.)

The 1990s were also the sustained entree to renewable energy, with the first wave of state renewable energy requirements – in 12 states – adopted prior to 2000.8 Utilities initially fought renewable energy standards, but opposition waned as utilities saw remote wind farms generating 100-500 megawatts of power as compatible with the traditional centralized utility model. State requirements for utility-scale renewable power were accompanied by the adoption of net metering statutes, allowing electricity customers to net their energy use and production on a monthly basis. These policies had a minimal impact until decades later.

The Third Wave of Change

It was economics as much as new state policy in the mid-2000s that powered a third wave of change, a wave that has yet to retreat.

A second tier of states adopted renewable energy standards (some with set-asides for distributed renewable energy), voluntary green purchasing programs, and numerous state energy efficiency standards. Some states and utilities adopted feed-in tariff programs or substantial incentive programs for distributed solar, such as the California Solar Initiative, or solar renewable energy credit markets. The market introduced third party ownership, providing substantial simplification of going solar for homeowners and businesses. Most important, the economics of solar – large and small – improved dramatically, leading to a surge in installations.9

Sensing the foundations shifting under the Utility 1.0 business model as energy use decreased and customers began generating more of their own power, states began experimenting with “decoupling” and “lost revenue adjustments.” These policies allow utilities to maintain revenue even as electricity sales fall.

These incremental policy changes are insufficient.

Solar energy, in particular, has become the flashpoint (in over 20 states) for the struggle between utilities and their customers for control of the future electricity system10. Unlike previous innovations, solar is rising at the same time that widespread use of smartphones and distributed computing could allow – with an open market for innovation – utility customers unprecedented power to shape their energy use and production.

This is the first of four parts of ILSR’s Beyond Utility 2.0 to Energy Democracy report being published in serial. Download the entire report and see our other resources here.

This article was originally published by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Reproduced here with permission