The battery storage industry has welcomed two landmark rulings that create new markets for their technology, but they face at least another two-year wait before the new rules come into effect.

Australia already has six big batteries operating on its main grid – with another five under construction and more than 50 in the pipeline.

But despite the fact that they can perform multiple tasks, their use is severely limited by the restrictions of the current market rules, which were designed for big centralised coal generators and which have only been very slowly adapted to new technologies.

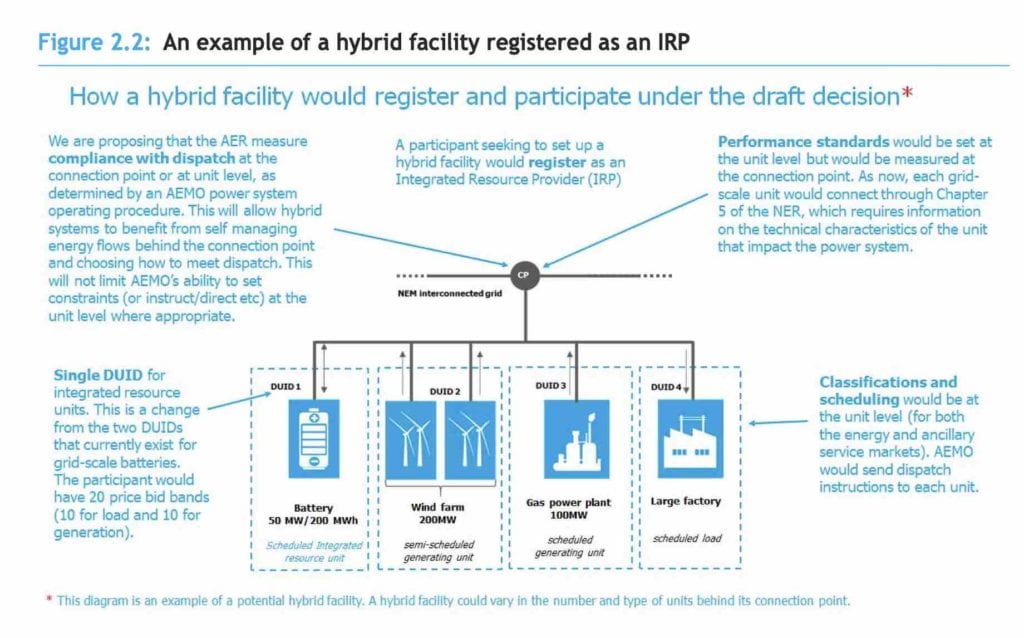

As an example, big battery storage projects located next to a wind or solar farm have been unable to do what most people assume they do – back up that wind or solar farm, or optimise or smooth or time shift its output – because the rules require they be registered and dispatched separately.

Likewise, some of the key services that they can provide – including incredibly fast and flexible responses to grid disruptions – are also not recognised by the market.

Big batteries have made several important interventions in the grid to help the lights on, but they have done it for free – and to demonstrate their capabilities – because there is no market to recognise their service.

It’s why state governments such as South Australia and Victoria have had to write direct contracts with the likes of Neoen for its Hornsdale Power Reserve and the Victoria Big Battery to ensure that the services they can offer to protect the grid are available when needed.

That is slowly starting to change. Last week, the Australian Energy Market Commission unveiled draft new rules that seek to solve the “hybrid” problem and allow different technologies to be combined at the same location, and to smooth out the creation of linked assets such as “virtual power plants” that aggregate thousands of smaller household batteries and other distributed energy resources.

The AEMC has also finalised its rules on the creation of a new “fast frequency response” market, where batteries and other inverter based technologies can be rewarded for delivering rapid response to grid disruptions in less than two seconds.

But neither new rule will be in place for another two years. The FFR proposal, although the rule has been finalised, needs the Australian Energy Market Operator to define the technical details, and as has been seen in discussions to date, there is a lot of controversy over how it should be done.

“It’s glacial,” said one battery storage executive, who preferred to remain anonymous because of the sensitivities of the discussions. “It’s slow, but it’s a great outcome,” said another.

The hybrid rule is also only at draft stage, despite being put forward by AEMO in 2019, which means it is open for further consultation and a final decision later this year. Even then, the AEMC says, it won’t be in place until 2023.

CEO of SwitchDin, Andrew Mears, said that the AEMC’s proposed rules would give more options to customers for how devices like battery storage systems will be able to contribute to the wider grid.

“The new rules proposed by AEMC will give battery owners, retailers and aggregators more freedom and clarity on how their assets can add value,” Mears said.

German battery producer sonnen, now owned by Shell, and which has made a recent push into the Australian market with local production facilities and involvement in government battery rollouts, said it would now adapt its own virtual power plant platform so that it could participate in the new fast frequency response market.

“The AEMC’s proposed rule reflects how dynamic home batteries are in strengthening the grid and sonnen will refine our virtual power plant technology to support the new faster frequency for demand response when the rule is passed,” sonnen Australia boss Nathan Dunn said in an emailed statement.

For more information on Australia’s big battery projects, see RenewEconomy’s Big Battery Storage Map of Australia