Ed: On Tuesday, in the second of our series on battery storage, this lengthy comment from Rob Campbell, the head of Vulcan Energy, captured out attention. We thought it was worth running as a separate article, to give attention that the issues he raises deserve.

“Competition is a great thing; it reduces consumer prices by encouraging business to be more efficient and innovative. There are hundreds of examples of prices driven by competition for the consumer dollar. Then there are great competition failures.

Most have been brought about by deregulation.

Example 1. Fixed wire telephony.

The concept of competition in fixed-wire telephony in Australia completely ignored the geographical range of our population, offering “billing rights” to all comers and then allowing duplicate infrastructure to be built only stalled advancement in Australia’s infrastructure. Without the advent of cellular technology, telephony would be priced well above where it is now. Mobile phones have disguised the flop that fixed line “competition” was.

Example 2. Pay TV

The outrage caused by the rollout of pay TV cabling through our suburbs, and the fact that most of this multi-billion dollar investment sits idle, again shows a failure to address the geographic realities. Foxtel now will install a satellite dish on the roof of a premise, rather than spend the money to run a co-ax to the street to pick up an existing connection point put there at great expense. If the amount of money Telstra(Foxtel) and Optus spent on this duplicate infrastructure was spent on one quality installation, we would be half way to the National Broadband Network (NBN) already.

Example 3. Electricity, the flop (or the biggest con).

“If we open up billing rights to all comers, the amount it costs to produce a bill and collect the money you owe will come down.” And “By connecting the eastern states with bits of wire, generators can compete to sell their electricity into the big market and this will force prices down.” Those are the lines we were spun at the time.

Two things have happened since this scheme came into play. Retailers’ margin (billings rights) costs have tripled to support business models that were never going to breed competition. The other most significant transpiration is that the national electricity market called for uniform reliability standards. This exposed, allegedly, huge deficiencies in the quality of our aging distribution networks. The result meant that competition policy had the exact opposite effect on consumer costs.

Distributors, mostly government-owned, have been gouging huge amounts of money from consumers to carry out “urgent and pre-emptive works”, to meet growing demand and increased reliability imposts. The chorus continues as the distributors, now corporatised, provide these services under a profit generating model, conveniently delivering hundreds of millions of dollars in profits to their owners, in the main state governments or investors with government-guaranteed returns. Faced with competition from renewables, the distributors are stuck in a situation where the reasons to spend have been substantially reduced, and with the advent of storage, the real possibility of having to shrink the network is unavoidable.

By embracing storage can distributors still generate profits?

The value proposition for storage at a residential level is tantalisingly close, without one cent of subsidy from the distributors, who stand to gain considerably from the mass rollout of residential storage. The commonly reported demand impact of a residential air-conditioner is a cost to the distributor of $3-5000.00. Whether this is true or not, who has the knowledge to question it?

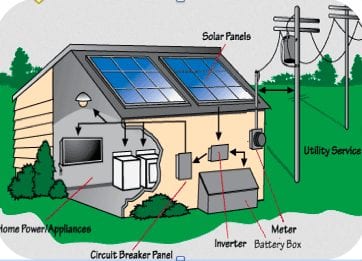

Why, then, can this situation not work in the reverse? If a residential customer installed battery storage which could directly reduce peak demand by 3 kilowatts, would that not have a $3-5000.00 benefit to the distributor? If so, why would the distributor not want to subsidise the installation of storage into every household in the country? Distributors allocate a demand average of 4-5 kilowatts per home when calculating the size of a distribution network. Integrated and reliable storage can reduce this to 1.5-2.5 kilowatts, half (or more than half) of what they need today. If 51 per cent of our bill is devoted to these costs, and we all pay for our own storage, we could expect our energy costs to drop by at least 25 per cent.

If we have solar to charge our batteries, we could all go virtually “off-grid,” using the network only on the rare occasion where our demand exceeds the capabilities of our storage or inverter. But how does the distributor make money out of reducing the size of the network? Based on publicly available information in Queensland, the amount of money expended on capital works on whole of network is $2.7 billion, with $1.05 billion spent annually on maintenance.If the distributors in Queensland were to subsidise residential storage to 200,000 homes per year at a cost of $600 million the net effect per year in reduced demand on the network amounts to 600MW, next year 1200MW, 1800MW and so on.

Queensland’s maximum demand sits at approximately 7000MW, with a base to peak variation of approximately 3000MW. This means that in a period of five years, the demand profile for Queensland could be a flat line at 4000MW. The ability to reduce baseload of 4000MW by at least 1000MW is easily achieved.

In theory, that is $2.1 billion in capital expenditure no longer required per annum. Even if this figure were to be halved there still remains a large amount of potential “profit” for the network owners.

Storage does not have to be confined only to Solar PV, or in fact single dwelling homes. The case for storage in apartments and similar situations is equally relevant where a power is available a suitable off-peak discount for charging of the storage units.

The ability for a distribution entity to generate profits while subsidising the rollout of residential storage is in plain sight. By the very nature of the model, the benefits for all involved can only increase, giving scope for reductions over successive years in overall electricity prices.”