The transition of Australia’s main grids towards 100 per cent renewables is more than a battle between wind and solar on one hand, and the powerful fossil fuel incumbents on the other – it’s also about who gets to provide the essential services to the grid.

Australia’s biggest transmission company, Transgrid, has recently conducted a tender over who can provide “system strength” in NSW as the biggest and most coal heavy grid in the country prepares for what could be a rapid exist of its big coal generators.

System strength describes the ability of the power system to maintain and control the voltage “waveform” following a disturbance, and came – more or less – free of charge with the synchronous generators operated by coal, gas and hydro plants.

That service will effectively be withdrawn as coal and gas exit the grid, and Transgrid wants to know who can fill the gap, and at what cost.

A market sounding conducted in March found no shortage of interest – some 60 different solutions including 10GW of “grid forming” battery storage proposals, another 10GW of existing or conversions of existing synchronous generators, and a further 5GW of other proposals, including pumped hydro and gas.

The company’s network chief Marie Jordan says periods of 100 per cent renewables are likely to emerge as early as 2025, and increase dramatically beyond that as more coal generators retire.

“We are acting now so we have the time to ensure emerging technology is tried and tested before the need for additional system strength grows beyond 2025 as more coal generators retire,” she says.

“Large spinning machines such as coal, gas and hydro generators have the ability to keep the grid stable and ride through disturbances, including lightning strikes or equipment trips.

“However, existing ‘grid- following’ renewable energy sources such as wind and solar don’t have the same capabilities and need to follow a strong signal from the network – or will disconnect.”

Transgrid has been looking at the example of South Australia, which has installed four “synchronous condensers” – large spinning machines that do not burn fuel, and are in fact a decades-old technology.

Those syncons have already dramatically reduced the need for gas turbines to spin in the background, and will likely eliminate that need altogether when the new transmission link is completed from NSW.

But the battery industry is pushing the idea of “grid forming inverters” that they say can do a similar job to the syncons, and at lower cost, as has been demonstrated in trials at the Hornsdale Power Reserve (then original Tesla big battery) in South Australia, and Transgrid’s own Wallgrove battery in western Sydney.

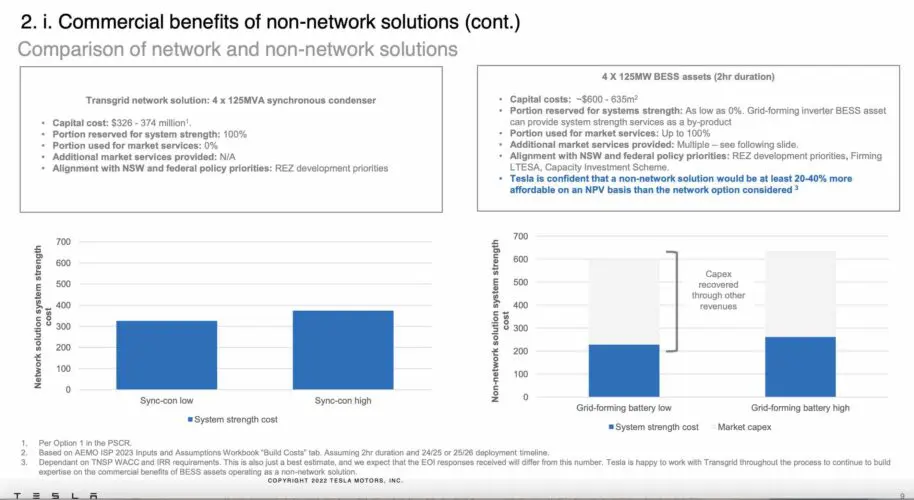

Tesla, which supplied the batteries and smart inverters (which it calls virtual synchronous machines) at both Hornsdale and Wallgrove, writes in a submission to Transgrid that batteries can do the job at lower cost, up to 40 per cent cheaper than the syncon solution.

Tesla notes that the capital costs of a grid forming battery wulkkl be considerable higher than syncons – around $600 million compared to around $350 million.

But it says the advantage of a battery is that it is not a one trick pony and can repay that capital by getting revenue in other markets. That will reduce the system strength cost to Transgrid by around one third, or possibly more.

“Grid-forming inverters, and BESS (battery storage) assets in particular, provide a solution that can be optimised in the long-term for both market and system strength services,” it writes in its submission.

It says “non-network” solutions (i.e not syncons) can provide a multitude of market services as well as network support to make them more cost effective than other solutions.

:”Given the flexibility of BESS to have features and functionality updated over the asset life, these services can also change over time to provide optimal co-benefits to the grid and the market.”