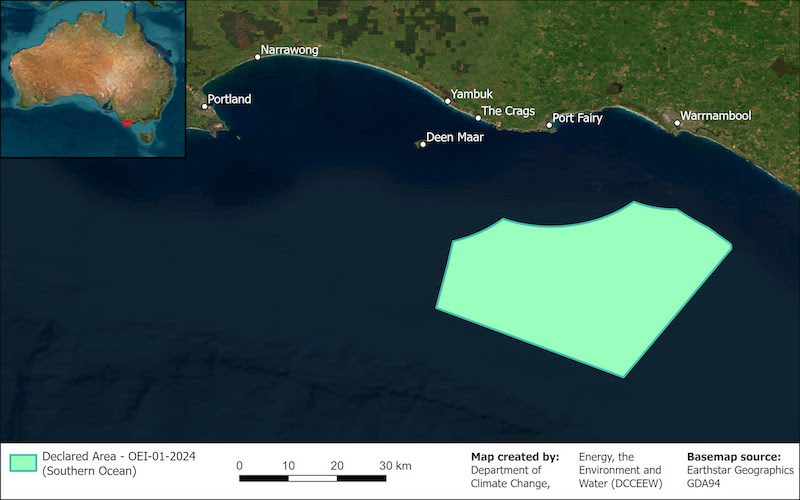

Australia’s third offshore wind farm development zone has been officially declared, with federal Labor on Wednesday announcing a drastically pared back 1,030 km2 area in the Southern Ocean off western Victoria.

The new development zone – which federal energy minister Chris Bowen says is one-fifth of the originally proposed zone – is located at least 15-20km from the coast of Victoria and no longer includes the contested area off South Australia.

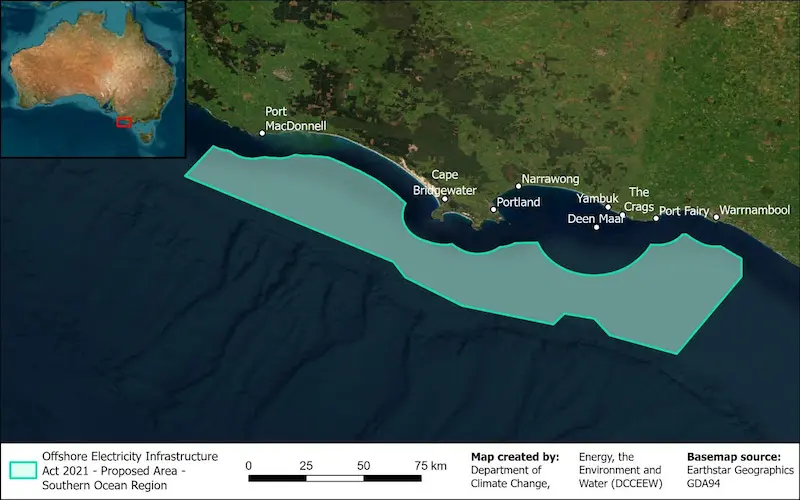

The original proposal comprised a 5,100km2 zone that stretched from Warrnambool in Victoria up to Port MacDonnell in South Australia, but after a couple of months of consultation it became clear there was trouble on the SA side of the border.

The South Australia government expressed concerns about the impact of wind farm development on fisheries industries in the area, and in particular the $187.5 million rock lobster industry, as well as marine life.

It also said that energy generated within the zone would be connected exclusively to the Victorian power grid, and not to South Australia, which already sources more than 70 per cent of its grid demand from (onshore) wind and solar and aims to get to “net” 100 per cent renewables by 2027 with its onshore wind and solar projects.

South Australia recommended the federal government moved the zone, or reduced the size to exclude South Australia waters.

The smaller block will force a change of plans for developers that have already telegraphed their interest in the South Australian side of the original zone, such as German company Skyborn Renewables and European company Bluefloat Energy.

- See RenewEconomy’s Offshore Wind Map of Australia

The shrunken zone could still host up to 2.8GW of offshore wind energy – enough to power over 2 million homes, or two-and-a-half Portland Smelters. The existing smelter consumes up to 10 per cent of electricity in Victoria.

Current assumptions suggest the industry might bring as many as 1,740 jobs during construction to Portland and 870 ongoing operation jobs.

“The Southern Ocean offshore wind zone has the potential to create thousands of new, high-value jobs and help secure cleaner, cheaper more reliable energy for regional Victoria,” energy and climate change minister Chris Bowen says.

“Australia has abundant renewable energy, the cheapest form of energy, and the government is committed to helping Australians benefit from these natural resources, including offshore wind.”

Environmental group Friends of the Earth is just as happy about the reduced zone, saying it shows an ability to balance industry with environment and cultural heritage protections and protects sensitive ecosystems such as the Bonney Upwelling, a significant blue whale feeding area.

Feasibility licence applications for the new zone will be open from 6 March until 2 July 2024.

Cost prohibitive?

Australian governments are well aware that offshore wind isn’t a cheap alternative to onshore renewables, having been repeatedly warned that offshore wind costs are just getting more expensive due to inflated supply chain costs.

But the latest contracts awarded in the US show that prices need to start coming down from eye-watering levels for these projects to be viable.

Two US offshore wind projects were awarded new contracts by the New York state government that saw the final pricing almost double to just over $US150 per megawatt-hour ($A230/MWh).

Equinor’s 810MW Empire Wind and Sunrise Wind, a planned 924MW project being developed by Ørsted and Eversource, last year petitioned New York regulators to adjust the prices they would receive for power generated from the planned offshore wind farms, the first contracts for which locked in an all-in development price of $US83.36 per MWh in October 2019.

Both are fixed bottom projects.

In the UK, the government lifted the ceiling strike price for offshore wind by 66 per cent, to £73/MWh ($A139/MWh) for fixed bottom offshore wind projects and £176/MWh ($A337/MWh) for floating offshore wind projects.

Australia is at the earliest stages of forming offshore wind zones and deciding on where commonwealth and state rights and responsibilities lie when it comes to planning rules, so it’s unclear yet where the final bill for the industry here will rest.

However, if the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union’s (AMWU) calls for stronger local content rules are heeded, that cost may begin to look more like those in the US, itself a challenging jurisdiction because of local content requirements including building all critical vessels in the country.

“This Southern Ocean offshore wind project’s promised economic and employment benefits will not be fully realised without stronger provisions on including local content,” says AMWU national secretary Steve Murphy.

“But without strong provisions to ensure that Australian-produced steel or Australian manufactured goods are included in the projects built in the Southern Ocean offshore wind zone, local workers and the regional communities who rely on them miss out on jobs and economic investment.”

Still a ‘no’ on taskforce

The federal government is not budging on Victorian energy minister Lily D’Ambrosio’s suggestion of forming a joint taskforce to manage the complex — and in some areas still to be established — web of state and commonwealth regulatory processes that offshore wind developers will need to negotiate, she told RenewEconomy last week.

Currently, there is little guidance for developers on how state and federal processes will coordinate, given the former has jurisdiction over onshore issues and the latter over offshore territory — but also over some onshore decisions as seen by the rejection on environmental grounds of the Port of Hastings as Victoria’s port to be developed to service the new industry.

“Given that there are several regulatory processes that the commonwealth needs to work its way through, and the state has its own regulatory processes that it needs to go through, having a joint equal partnership would certainly help,” D’Ambrosio says.

Already in existence is a federal working group with states and territories that is part of the National Energy Transformation Partnership, designed to deal with regulatory hurdles, and Victoria and the commonwealth have a separate MoU on offshore wind which sees ministers meet at least three times a year and help with information sharing between government departments.