Australia has the opportunity to make an incredibly rapid transition to a mostly renewable energy-based grid within two decades with a strong carbon price and other incentives, but will most likely maintain the status quo and increase emissions from its grid if the carbon price is removed.

That is the broad conclusion of the Climate Change Authority’s draft investigation into the emissions reduction potential for the electricity report, included in a 245-page appendix to the 176 page overview released last week.

The scenarios unveiled by the CCA would make even the most optimist Green policy seem modest in comparison. By 2030, it says, renewables could make up 69 per cent of Australia’s generation (that includes a large slab of geothermal) and by 2050 the grid could be almost emissions free.

That is almost a complete reversal of the current make-up of Australia’s electricity grid, which is dominated by coal and is one of the most energy intensive in the developed world. This table below outlines the scenarios envisaged under the modelling.

The prognosis is not really that outlandish. Renewables already compete with new build fossil fuel generation, but because of the oversupply in the market, nothing will be built unless the renewable energy target forces the issue. Maintaining the RET as is would force some coal-fired generation to be permanently sidelined, rather than just mothballed, and if a carbon price was high enough that would accelerate that retirement rate after that date, because it would mean wind and solar would be able to compete with existing generation, even with its sunk costs. As new capacity was required it wouldn’t require a person of genius to figure out what to build.

But it’s a scenario that probably won’t happen under the current government. That’s because it has vowed to repeal the carbon price. And the status of the RET is also under question, because the Abbott government has insisted on yet another review, to respond to generator concerns about falling demand.

The CCA makes the case that the range of scenarios depending on the price of carbon are broad – from no further reductions in emissions intensity, to quite significant ones.

Even though the criticism of abandoning a carbon price is inferred, the report should not necessarily be taken as a damnation of Direct Action, because those policies, which include an emission reduction fund, are not assessed – mostly because their details are not known.

The new government will argue that its emissions reduction scheme will selectively buy abatement and reduce emissions from the sector, but that depends on how it is structured – whether it is looking to reduce emissions from continuing generators, or using money to take dirty generation out of grid.

A UNSW study last month noted that paying for one or more coal fired generator to be removed would not result in significant abatement, because its place in the merit order would simply be taken up by other coal fired capacity. It’s not that coal fired generators should not disappear, it just seems pointless and economically inefficient to pay them an exit fee, apart perhaps from assisting in remediation costs, which now appear to be discussed.

However, the CCA report makes it clear that having no carbon price will likely reverse the gains made in recent years. The renewable energy target – should it be kept as is – would lower emissions from where they would other be, but the Australia grid would emit 14 per cent more greenhouse gases in 2020 than it did in 2000. By 2030, the increase in emissions from electricity could be 40 per cent.

This would be a lost opportunity. The CCA notes that the electricity sector is the country’s largest single contributor to emissions, accounting for 33 per cent of the country’s output. It also offers the biggest opportunity for reductions, as a majority renewable scenario suggests.

The details of CCA’s forecasts are interesting. It relies on modeling from ACIL Tasman, and forecasts that under a high price scenario, the share of rnewables in Australia’s generation could be 69 per cent by 2030, and coal could be as little as 9 per cent. That is almost a complete reversal of the current situation.

The ACIL Tasman model has geothermal providing up to 28 per cent in this scenario, with solar up to 14 per cent and wind up to 20 per cent. The rest is resumably hydro and other renewables such as biomass.

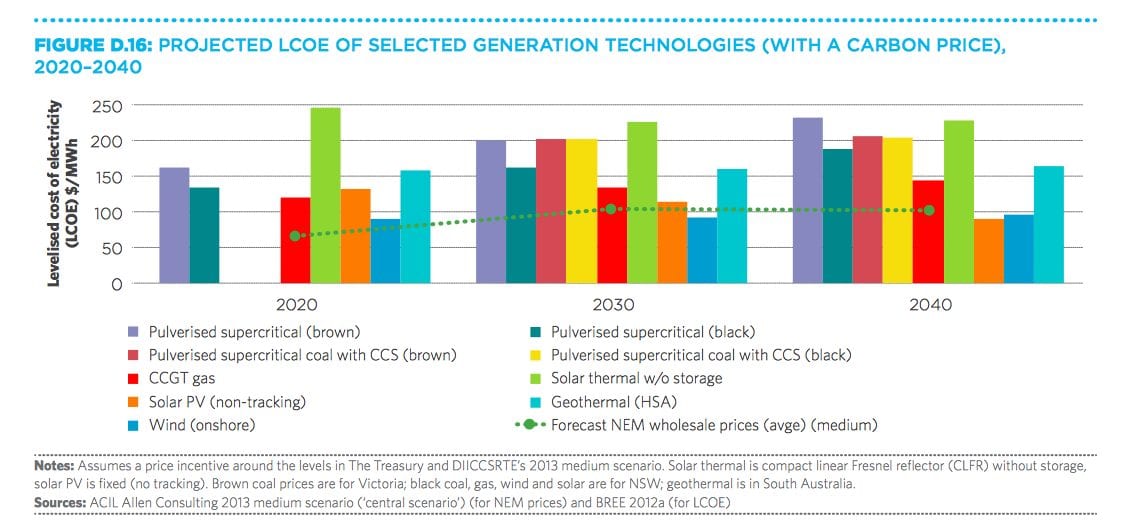

The basis for the ACIL Tasman modeling is revealed here in its view of the cost curve (see graph below). Its view of the current prices of renewals seem to be more realistic than those of the Bureau of Resource Economics and Energy, but it still suffers from a pessimistic view of where those prices are going.

It only assumes a 10 per cent fall in solar PV prices over the next decade and a 5 per cent fall after that. Solar thermal costs change little, but that is possibly because it uses compact linear Fresnel technology as a base, and without storage. It is not clear why it has done that, apart from the fact that nearly all of Australia’s solar thermal installations to date (two solar booster projects in NSW and Queensland) are based on this technology. However, CLFR is hardly deployed anywhere else in the world and the new solar towers with storage that are being built in the US are talking about technology costs of below $150/MWh within a few years.

Still, the ACA suggests that wind and solar could account for up to 50 million tonnes of emission reductions. Further reductions in the cost of solar will likely mean less coal-fired generation.

The RET guarantees that renewables are deployed in the next decade, eliminating any possibility that there will be a “lock-in” of newly built high emissions generation. But the question is what happens after 2020 if there is no carbon price and the RET is not extended. That could alter the scenarios dramatically back towards a heavy reliance on fossil fuels by 2030, and no abatement from the electricity industry. In fact, as this graph illustrates, it could result in a sharp increase.

That won’t help Direct Action, which at the moment relies exclusively on domestic abatement to reach the minimum 5 per cent target – even though the CCA has said this is inadequate and not credible and should be lifted to a minimum 15 per cent, and possibly even 25 per cent. The CCA notes that electricity emission reductions could account for half of the Direct Action target.

In the longer term, energy efficiency will be crucial. The CCA says it could account for 40 per cent of emissions reductions achieved from 2020 to 2030, a result of Australia’s relative poor performance on electricity efficiency and productivity compared to countries with a similar GDP. This is particularly the case with buildings – Australia actually rates quite well on appliances, lighting and equipment improvements.

Still, improvements in building efficiency could reduce emissions, relative to 2000 levels, by about 12 Mt/CO2-e in 2020, and improvements in the efficiency of electric appliances could reduce emissions, relative to 2000 levels, by about 20 Mt CO2-e. The greatest savings are likely to come from water heaters, lighting, HVAC systems, motors and other electric equipment