Queensland, the so-called sunshine state with the least amount of renewables and the heaviest dependence on coal in the country, may be about to make a big leap forward.

The state Labor government has had a 50 per cent renewable energy target in place since 2015, but has done pretty much nothing about it.

Its renewable energy share in the last 12 months remains an embarrassingly low 20.7 per cent, which is probably the reason why energy minister Mick de Brenni has decided to come up with a 10-year plan, which is due to be released in the next few weeks.

The Australian newspaper reported on Thursday that Queensland may be about to lift the 50 per cent target that it already appears to be struggling to meet, although the speculation is unsourced and contains no new figure, and appears to be largely based on some optimistic observations from CleanCo boss Tom Metcalfe this week.

A spokesman for de Brenni would not comment when approached by RenewEconomy. “The energy plan will help ensure the government meets its renewable energy targets,” he said.

But if Queensland is to lift its renewable energy target it won’t be able to pat itself on the back for a job well planned: It just happens to find itself in the midst of a green hydrogen boom and can thank its legacy port infrastructure and the massive interest from private investors.

Although Queensland has little in the way of renewables at the moment – and recently made the madcap decision to replace the exploded Callide C coal turbine with another one – there is plenty in the pipeline.

Already, the country’s biggest wind farm, the 1GW Macintyre precinct majority owned by Acciona, and the country’s biggest solar project to date, the 400MW Western Downs solar farm owned by Neoen, are under construction. Western Downs already has more than 100MW of its capacity on line.

More wind farms are being built. Andrew Forrest’s Squadron Energy is working on the first stage of the 450MW Clarke Creek wind farm, Neoen is building the 157MW Kaban wind farm, and RES is building the 180MW Dulacca wind project.

The first big battery, Wandoan South, was recently commissioned and handed over to AGL to support its portfolio, while another is being built at Bouldercombe by Genex, which is also building the private sector’s first pumped hydro plant in nearly four decades at the old Kidston gold mine.

Spanish giant Iberdrola this week confirmed it is looking to invest billions into its renewable energy portfolio, which includes the 1GW Mount James wind and the 360MW Broadsound solar projects.

Genex recently bought the rights to the massive 2GW Bulli Creek battery and solar project, and has more wind and solar plans for around the massive Kidston pumped hydro facility.

Forrest’s ambitions for Clarke Creek do not end with the first stage wind farm. He hopes to build a massive $3 billion renewables hub that would combine wind, solar and storage, and this may get even bigger if his green hydrogen plans come to fruition.

Rio Tinto is also looking for multiple gigawatts of renewable capacity to help power its smelters and refineries, which include the Boyne Island smelter near Gladstone. Energy Estate and RES have ambitions to deliver 4GW of wind, solar and storage in their Central Queensland Power consortium.

All of which adds up to a lot more than the 10GW cited by CleanCo’s Metcalfe as needed to meet the 50 per cent renewable energy target. The reality is that no state and federal government has set a renewables target that it hasn’t been able to meet, although the federal Coalition did its best to scuttle the national RET scheme.

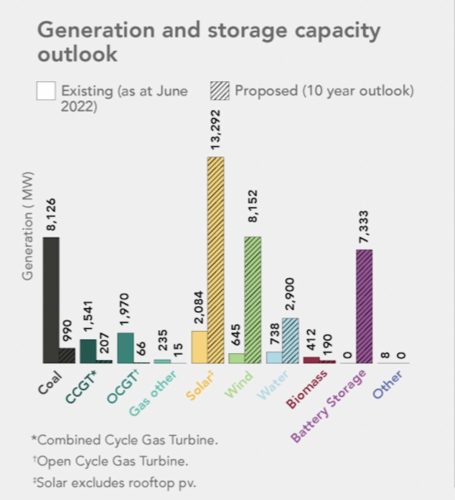

In fact, the projects cited above barely scratch the surface. According to the Australian Energy Market Operator’s recent Integrated System Plan, which assumes an 80 per cent share of renewables for the main grid by 2030, there are more than 21GW of large scale wind and solar projects that could be built in the next 10 years.

And that does not include rooftop solar, the more than 7GW of battery storage, and another 2.9GW of hydro assets. And this, it should be noted, is the current “step change” scenario.

The “hydrogen superpower” scenario, considered by many to the the most likely within a few years, suggests all coal generation could be gone in little more than decade, and that would include Queensland.

De Brenni’s role, then, is to make sure that the infrastructure is in place to support the massive build out, and make it look like the government is doing something. The recent sweep of inner city federal seats by The Greens appears to have concentrated the minds of state Labor.

The good news for Queensland is that it still owns the major network providers, the two legacy generation companies – Stanwell and CS Energy – along with CleanCo, so it is within its power to be pro-active.

Recently, the state secured $160 million in finance to help super-size the grid connection for the Macintyre precinct, effectively creating a new renewable energy zone. Federal Labor’s Rewiring the Nation plan will provide another $20 billion to support such transmission needs around the country.

It all means that if Queensland does not get to 50 per cent renewables by 2030, then it has no one to blame but itself. The likelihood is that it can go a lot further, and its biggest challenge may be how to ensure jobs, and a just transition, for the coal communities that are likely to be most affected.

But in a sign of the times, and the growing realisation that coal generation has had its day, even the country’s most notable coal grump, former energy minister and now Queensland Resources Council chief Ian MacFarlane, said the coal lobby he heads would support the transition to renewables, as long as the plan was clear.

“We are more than happy if they increase their renewable energy target as long as they can maintain stability and prices for electricity,” he told The Australian, adding there were still plenty of jobs for coal miners in the export market.