A system with lots of wind and solar will likely have prices that are very low most of the time and very high at other times (binary price structure or fat tails (leptokurtosis) from a statistical perspective). The Integrated System Plan (ISP) produces the lowest cost system to society, but this does not mean that individual producers will earn a return.

As far as I can see, when we build the capacity modeled in the ISP and compare it with AEMO’s demand projections there will be lots of spilled energy. Producers will not get paid in an energy only market for spilled energy.

An alternative is adding more storage and having less wind and solar, or more gas. Gas is out because of carbon and cost. Storage is not the most economic outcome from a system point of view because of seasonality, as much as other factors.

If we accept that the ISP is indeed a plausible system-wide, low-cost solution then it’s unlikely to be built by producers in an energy-only market because they won’t get a return.

An alternative prospect that, in my opinion, needs more serious scrutiny is a system-wide capacity market. Getting the system capacity built is the main issue, the energy will take care of itself.

Unfortunately a system-wide capacity market may require planning. Note that this is not (just) dispatchable capacity, it’s more about getting the solar and wind capacity built. Whole-of life, whole-of capacity power purchase agreements (PPAs) will get the job done. An energy market may not.

I’m far from sure I am on the right track; maybe more faith in markets is required. Still, wind and solar don’t respond to price signals, they just produce as available. The energy price is as irrelevant to the production system as it is for rooftop solar.

I can also say that negative prices are going to be a feature of the grid until must-run coal generation exits. Those negative prices will be accompanied by extensive curtailment. Two-thirds of utility solar on the grid was curtailed at one point on the weekend and we are still in Winter 2024.

From that point of view I think it’s very disappointing that the Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS), which is meant to build confidence as much as anything else, doesn’t provide negative price protection.

It’s self defeating to have a support system designed to defend the low case which has a massive unpluggable hole in it. Again, I might be quite wrong, the workings of the market will defeat any one analyst, let alone a semi retired amateur like me.

An energy only market is not the right design for a heavily renewables grid

Wind and solar have essentially zero marginal costs and so are not responsive to price signals. An energy only market is based on marginal cost pricing. It is almost definitionally inappropriate to have marginal price setting when that price will be close to zero.

A highly renewable grid is likely to have a binary price structure. Most of the time when renewables are abundant price will be low. In wind droughts prices will be high.

Wind and solar may have missing money and lack of price signal. Evidence of this is already abundant even when variable renewable energy (VRE) share is less than 40%.

Solar is the cheapest energy but cannot earn a return so there is little or no price signal. So now solar has to be coupled with storage to be built. In South Australia we can already see wind struggling to earn a return. Assuming enough wind is built the same situation will emerge in other states.

A separate but related issue is that new capacity has to be built before old capacity is closed. This requires investors to see a clear enough price signal to justify the investment. If that price signal isn’t there the new investment doesn’t happen and then existing capacity is subsidised to remain in the system.

Transmission builders need to be confident that enough capacity will be built to justify the cost of the transmission. The transmission and capacity, ideally, have to be built in a coordinated fashion – but markets are not really a good system for coordination.

If I look at the LNG build-out in Queensland, each project was vertically integrated; that is, APLNG built the wells, built the pipeline, built the Curtis Island processing facility. In electricity, the old fashioned separation of “monopoly” assets from generation and retail is producing a coordination nightmare.

Monopoly regulated networks are themselves not properly incentivised to orchestrate behind the meter resources with the utility scale sector.

A rising tide floats all boats

It’s not always simple to isolate the structural outlook for prices from market conditions. For instance, over the past six months a wind drought has raised prices received for all fuels.

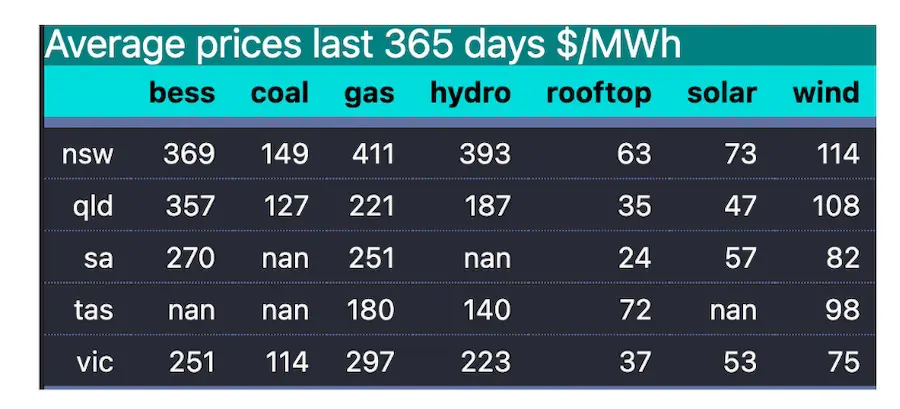

Average prices by fuel. Source: NEM Review

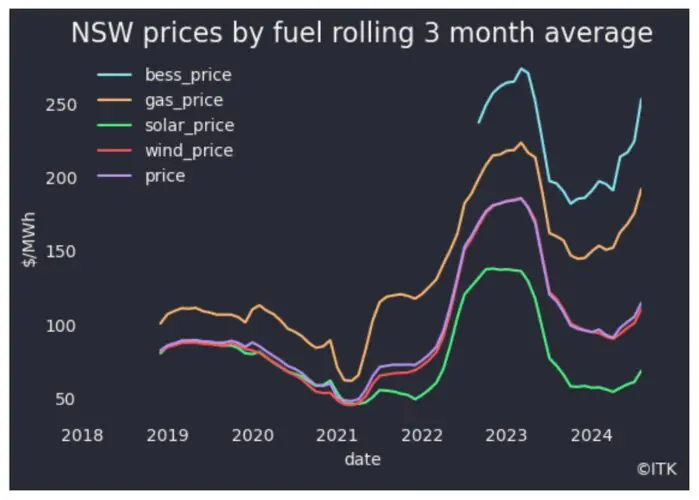

And if I look back through time, even utility solar has been able to earn something close to LCOE in most states most of the time. For instance look at NSW…

NSW prices by fuel. Source data:NEM Review

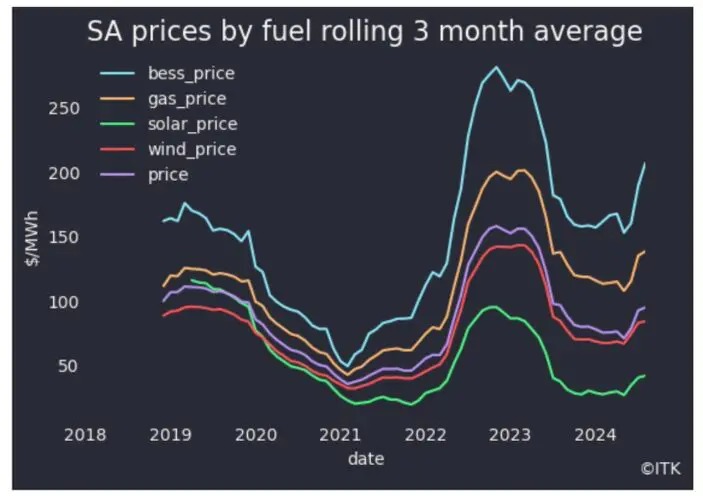

…or South Australia.

SA prices by fuel. Data source:NEM Review

The figures also show that the price wind generation gets is close to the time-weighted price in both states.

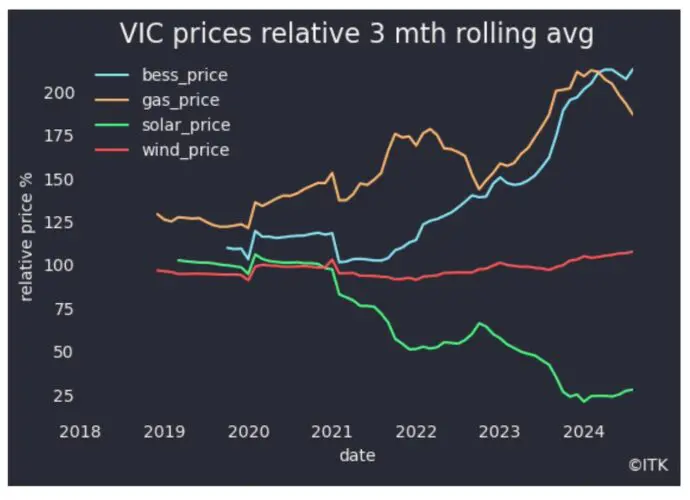

Relative prices give a view of structural changes

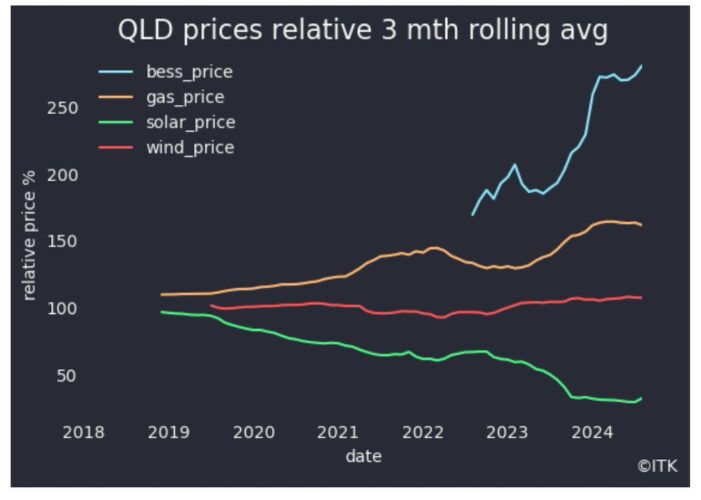

Borrowing once again from share price analysis, we can look at relative prices. The relative price for this note is the fuel dispatch weighted price/ flat load or time weighted price * 100. Such an analysis shows that in all the main land regions, solar’s relative price is declining. For the time being wind is able to get right around the average flat load price. Equally the firming price relatives have gone up.

Vic price relative. Data source: NEM Review

QLD fuel price relative. Data source: NEM Review

NSW fuel price relative. Data source: NEM Review

Even in South Australia wind has held its price relative close to 100. That’s because the share of wind in South Australia’s fuel mix has stopped rising.

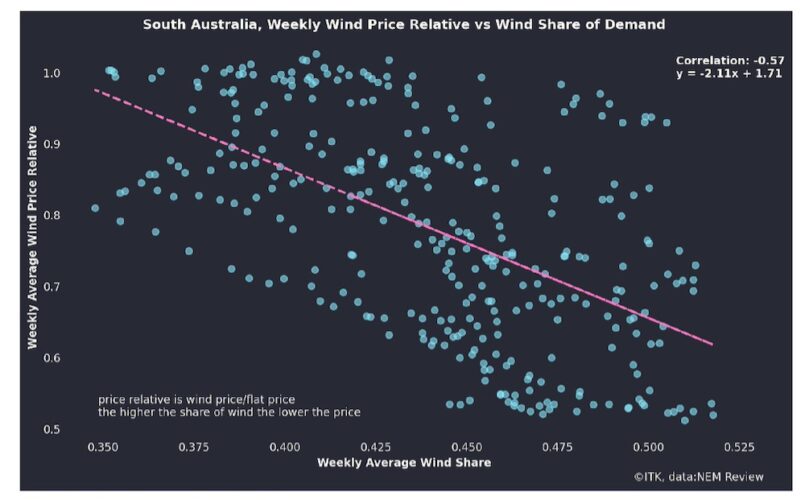

Still, by comparing the wind share in South Australia with the wind price relative we can see that, as the share increases, so does the discount to the time weighted price.

South Australia wind price relative v wind share of demand. Data source:NEM review

Will renewables earn the return needed?

ITK’s price modelling and a couple of bits of evidence from the past few years lead to caution in expected returns for wind and solar generators in a highly renewable system.

Looking at what’s happened, it’s no surprise to anyone that solar prices don’t seem high enough to justify investment other than in NSW – and even then, only just. That’s because, of course, utility solar competes with rooftop solar in the middle of the day and there is an overall oversupply.

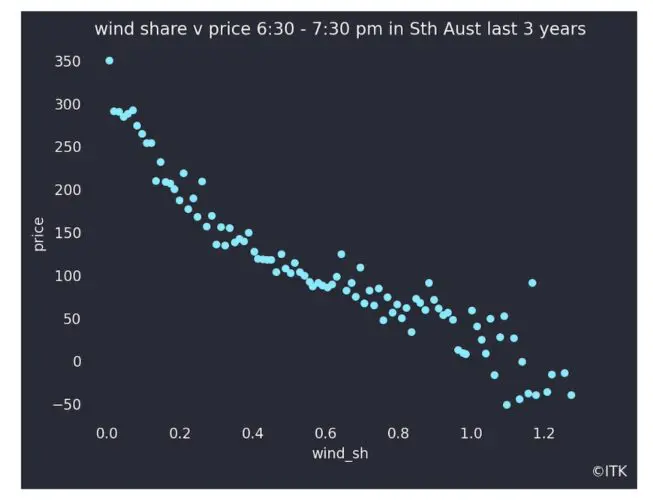

Wind share in South Australia has been static for a few years now, that’s a message in itself. An even clearer illustration of the impact of wind volume/share on the wind price received is to look at the evening price window in South Australia – i.e. little or no solar – and then look at what happens to prices as the share of wind rises.

SA wind share of supply v wind price. Data source: NEM Review

The one thing we know about a high variable renewable energy (VRE) system is that the supply of wind and solar will be volatile. What’s less often considered is that when there is lots of wind and solar, prices will tend to be low. When there are wind and solar droughts, typically in May-July in the southern states, prices will be high.

Most consumers will see the average of the high and low prices as it’s the job of the retailer to manage the risk. Overall, average prices will possibly be lower than right now. However all the participants in the system may end up unhappy.

Definitionally, prices will be lower when there is lots of wind and solar. Just as definitionally the wind and solar wont be able to access the high price periods because they only happen when there isn’t much wind or solar.

Equally those capacity providers that do nothing but sit around waiting for a wind and solar drought will need very high prices in the droughts to compensate. So what consumers see is one thing, but the wind producers run the risk of getting low prices when wind generation is high and being unable to access the high prices when wind generation across the system is low.

Prices are becoming strongly seasonal and are likely to be very low leading to Christmas

Only a few years ago price spikes were common in Summer. Air con demand was high, transmission ratings dropped and the old coal generators were prone to breaking down from the need to run flat out in both the day and evening.

How times have changed. Now in Spring/Summer, solar pushes prices towards zero in the day and the coal generators then don’t have to work so hard and so cope better in the evening peaks. Transmission doesn’t have to work hard until the evening when the worst of the heat has gone (Dynamic line ratings right?).

Instead, it’s late Autumn when prices spike – particularly May/June when wind and solar output are seasonally down.

Despite this year’s particularly low wind output, the underlying capacity of solar and wind keeps growing, providing shorter and shorter windows for high prices. I know retail consumers getting $900 or $1000 bills for just one month in 2024. It was one such $300 bill a few years ago that made me upgrade my own solar and battery system, but its only one month.

Solar output will pick up 50% over the next few months, but already weekend prices in Victoria and South Australia are close to zero on a 24 hour average basis, never mind the middle of the day. Prices have fallen further this week.

Time of day prices 3 days ended Sunday Aug 25. Data source: NEM Review

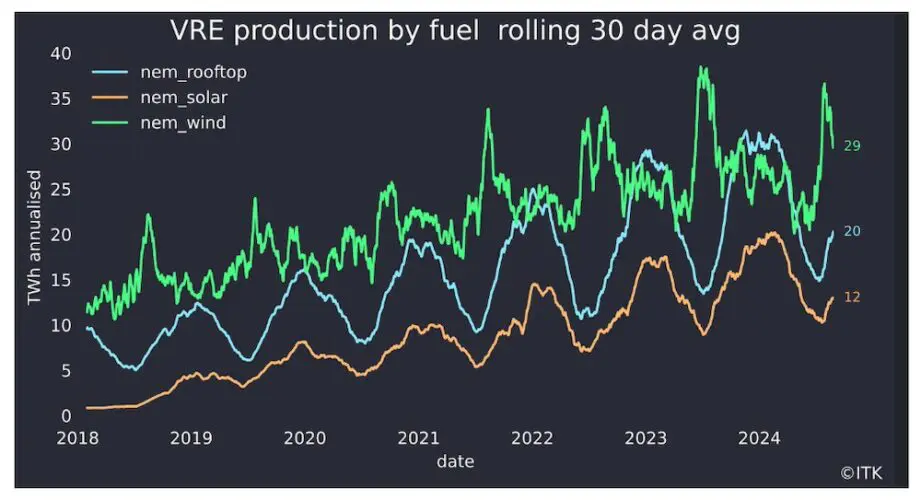

VRE production annualised. Data source: NEM Review

It’s a long way to 2035

Unfortunately we will be stuck with coal generation until about 2035. Not only that, the market will surely be structurally distorted until then. Even if I left government intervention in the form of the various state schemes and the federal CIS out of consideration, it remains the case that:

– New generation has to be built before old generation can be closed. This will result in a near-term surplus. Once again, the Queensland LNG provides an excellent example. One the electricity industry stakeholders will pay no attention to, but nonetheless.

In Queensland, the wells had to be drilled before the LNG plants were ready. That’s because well drilling is an ongoing process and takes time. So in the year before the LNG capacity was commissioned there was lots of surplus CSG sitting round and the spot gas price fell to $1/GJ. Some consumers of gas got sucked in by this and didn’t sign medium-term contracts at higher prices, but prices that still seem low by today’s standards.

The only reason that we aren’t seeing the same thing in electricity is because the electricity industry has so many different stakeholders and so many conflicting agendas that no one can do anything. It’s pretty much a paralysed industry. But eventually transmission, renewable developers and governments will work something out. I hope. And when they do, they will build new capacity and there will be a surplus.

– The big gentailers have reiterated that they will not build the new wind and solar, or at least only a minimal amount. They intend, as a bunch, to build dispatchable power and leave wind and solar development to someone who’s good at it. As a result they will either lose market share or will have to sign PPAs.

– The coal generators, despite significant capex, are increasingly unreliable. No owner is going to spend more money than necessary for assets with relatively short lives.