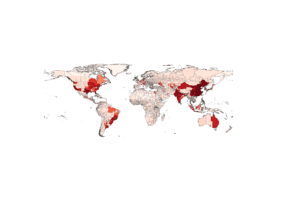

Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland are among the top 10% of global jurisdictions most at risk from the physical impacts of climate change, according to a new report ranking the physical climate risk of every state, province and territory in the world released today by The Cross Dependency Initiative (XDI).

XDI’s Gross Domestic Climate Risk ranks over 2,600 jurisdictions to 2050 according to modelled projections of damage to the built environment. That includes damage caused by flooding, forest fires and sea level rise. The report also identifies which of these jurisdictions sees the greatest escalation of modelled damage from 1990 to 2050.

Australia’s unique vulnerability to climate change is a major policy point. In May last year Climate Council released a report that found that by 2030, one in every 25 properties across Australia will be uninsurable by today’s standards, categorised as ‘high risk’ because of soaring annual damage costs linked to extreme weather and climate change.

That vulnerability is particularly acute on the East Coast of Australia, which has always been prone to extreme weather events linked to a pre-existing cycle of weather variability known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which is predicted to worsen with climate change (though the exact future of the ENSO cycle is very much under debate).

In addition, sea levels in the western Pacific Ocean are rising at almost two to three-times the global average rate.

But the whole of Australia will face unique challenges in the decades ahead, with temperatures expected to rise unilaterally across a country already vulnerable to extreme heat.

Dr Martin Jucker is an expert in climate dynamics who lectures at the Climate Change Research Centre at UNSW and is also an associate investigator with the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes. Jucker says he’s not at all surprised by the high ranking of Australia’s eastern states.

“Australia, and the east coast in particular, is a region defined by extremes,” he says. “Either it’s a drought or a flood, there is rarely anything in between.”

Jucker says the ENSO cycle is just one component of this extremity, which is working in combination with sea level rise and warming waters off the east coast in the Coral and Tasman seas.

“That means there is a lot more energy available for storms along the coast,” Jucker explains. “Together with a warmer atmosphere, which can hold more water vapour, this means we should expect storms to become stronger and carry higher flooding potential along the coast.”

Agus Santoso, a senior research associate at the Climate Change Research Centre at UNSW Sydney, agrees.

“There is generally a projection of drier conditions over the east coast, associated with the expansion of the subtropical dry zone,” he says. “But more occurrences of extreme rainfall events are also on the cards because of the increased capacity of a warmer atmosphere to hold more moisture.”

“In addition, there is the prospect that ENSO and IOD (Indian Ocean Dipole) variability can be enhanced in a changing climate, because of stronger air-sea interactions on a warmer planet,” he adds. “So we should also be ready for more extreme conditions associated with these energised climate cycles.”

Looking globally, the report shows that globally significant states and provinces in China and the US – which the report’s authors call the ‘engine rooms of the global economy’ – are among those most at risk.

For example, two of China’s largest sub-national economies, Jiangsu and Shandong, top the global ranking in first and second place, while over half of the top 50 are in China. After China, the US is the second most at-risk nation with 18 states in the top 100, including Florida, California and Texas. Other globally-significant economic hubs in the top 100 include Buenos Aires, São Paolo, Jakarta, Beijing, Hồ Chí Minh City, Taiwan and Mumbai.

But according to the report South East Asia experiences the greatest escalation in damage between 1990 and 2050 of any region in the world.

In terms of the causes of climate-related damage, riverine and surface floods combined with coastal inundation topped the chart for most predicted damage.

XDI CEO Rohan Hamden says the organisation has released the analysis in response to demand from investors, so by its nature it focuses on the economic costs of extreme weather rather than the human toll – though the two are intimately connected.

“This is the first time there has been a physical climate risk analysis focused exclusively on the built environment, comparing every state, province and territory in the world,” Hamden says. “Since extensive built infrastructure generally overlaps with high levels of economic activity and capital value it is imperative that the physical risk of climate change is appropriately understood and priced.”

The financial cost of extreme weather can be major, both abroad and at home. Extreme flooding in Guangdong in June 2022 caused an estimated 7.5 billion yuan in direct economic losses (more than US$1 billion), while Hurricane Ian, which struck densely populated parts of Florida in late September 2022 caused an estimated US$67 billion in insured losses.

According to the Insurance Council of Australia, the extreme floods that swept South-East Queensland and New South Wales in the first half of 2022 are estimated to have caused AU$3.35 billion (more than US$2 billion) worth of insured loss – on top of the 22 deaths, thousands of people made homeless, and the countless personal traumas experienced.

When asked how Australia can shore up its eastern cities and towns to protect against the coming crisis, Jucker is clear in the first instance.

“Stop burning fossil fuels,” he says. “Then, explore ways to prepare for more rain when it rains, more drought when it doesn’t, and more heat when the sun’s up.

“This may seem to hurt, but it will also spawn a lot of technological innovation. Nothing is better for the economy than innovation, so there is a positive side to all of this if only we let the innovation bloom rather than trying everything we can to keep things the way they are now.”

That’s the focus of the ARC Centre of Excellence in Climate Extremes that Jucker is a part of. CSIRO is also dedicating a large portion of its research to climate adaptation – that is, how to manage those impacts that we cannot avoid. In October 2021, the Federal Government released its National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy 2021-2025, which looks to drive investment, improve information and services and assess progress over time.

“Because the impacts of climate extremes are multidimensional, we need to increase our resilience by investing more in safeguarding the environment, resources, infrastructure, health, and the economy,” adds Santoso. “I’m not sure if there is a perfect one-size-fits-all solution.”