Imagine a world in 2050. Everyone drives an (electric) car, homes have all the gadgets, appliances and nick-nacks. The public transport system is emissions free. Mining work and transport is electrified, and diesel is dumped. Electrification has taken place in much of the steel industry. And it is all emissions free. It might be powered by 100 per cent renewables – the sun, wind, the sea, and geothermal, hydro and biomass. And the economy is still strong.

Welcome to the zero carbon world awaiting Australia and much of the rest of the world.

Major new analysis – Pathways to Deep Decarbonisation – produced by Australia’s ClimateWorks, along with ANU, shows that 15 of the world’s biggest economies can move to “net carbon zero” by 2050, and it need impose no extra costs over business as usual. In fact, electricity bills will be lower than what they are now. Economic growth will remain more or less the same, and the benefits, in terms of health and the environment, will be enormous.

The report is timed for the New York climate summit being hosted by the UN this week, and in the 12 months leading up to the Paris event that will hopefully result in a new climate treaty next year. It is designed to help change the political rhetoric around decarbonisaion. In Australia, only one party, the Greens, talks in terms of net carbon zero by 2050, and of higher renewable energy targets. Yet this report says not only is it necessary to meet climate goals, it is eminently doable.

Anna Skarbek, the executive director of ClimateWorks, says that Australia’s political rhetoric needs to change quickly. While the Abbott government is talking of the need to “cut” the renewable energy target down to a “real” 20 per cent, for “fear” that it might reach 25 or 26 per cent by 2020, Skarbek says that to achieve climate goals, Australia’s renewable energy target needs to be at least 50 per cent by 2030 – and then carbon free by 2050.

“There are many pathways for Australia to substantially reduce emissions, but all include greatly improved energy efficiency across the economy, a nearly carbon free power system and switching to low carbon energy sources in transport, buildings and industry,” Skarbek says.

“Taking the carbon out of our electricity system provides the largest reduction in emissions. Then we can use the carbon-free electricity to replace petrol in cars, and gas in buildings and some industrial processes.”

“The move to a low emissions electricity system can be developed with technologies that exist today. But we need to move faster – this report shows we’ll need at least 50 per cent renewable electricity by 2030 to achieve a decarbonised electricity system in the time we have left to stay within the carbon budget.”

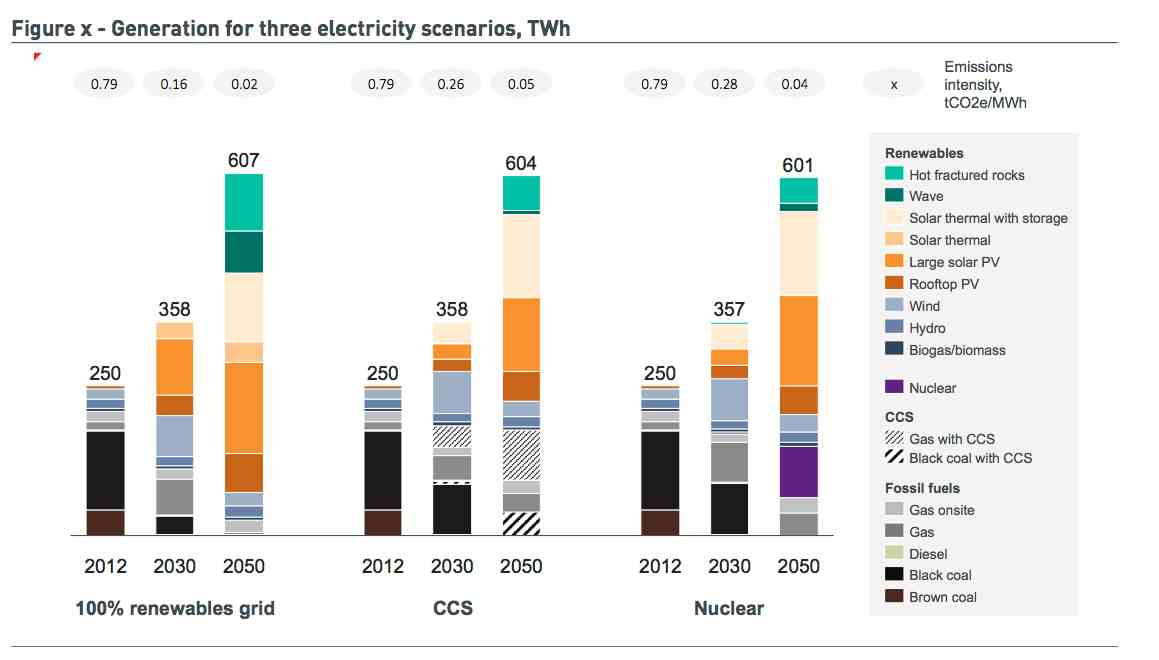

Indeed, as this graph below shows, whichever the scenario that Australia adopts, it needs to get to around 50 per cent renewable energy by 2030. And in all scenarios, even those that hope for cost-competitive carbon capture and storage, renewable energy is the dominant technology, and solar provides at least 50 per cent of all generation.

By 2030, under the renewable scenario, coal is nearly eliminated, although it plays a greater role in the other scenarios because CCS will take a decade at least to bring into production (if it can ever deliver the costs, which many think it won’t), and nuclear will not have a presence before 2030.

Even then, it is assumed that nuclear would provide no more than one-quarter of generation – and this is based on the rather generous cost estimates of past government reviews, and does not reflect the significant cost declines that can be expected of solar. Note however, that the emissions per MWh is the renewables scenario is nearly half of that entertained in the CCS or nuclear scenario – that’s because coal generators get to pollute for many years longer in those scenarios.

It is though a guide. What is clear is that in any scenario, solar will dominate, accounting for at least 50 per cent of generation in all three scenarios through a mixture of rooftop PV, large-scale PV, solar thermal, and solar thermal with storage. Wind, biomass and hydro will play significant roles. The main question is what technology provides the balance of dispatchable energy – pumped hydro, wave energy, geothermal energy, solar thermal with storage, battery storage or some other. It may be a mix of all.

Head of research Amandine Dennis notes that the cost of renewables such as solar is falling rapidly, meaning that incomes will increase faster than the price of electricity. With improved energy efficiency, this means households could have lower electricity bills than today, prior to any fuel switching.

“The remainder of fossil fuel use in the economy is shifted to either bioenergy or lower emissions fuel such as gas where possible, particularly for freight and industry. There is the potential to entirely offset any residual emissions by carbon forestry plantings.”

As this table shows, economic growth will remain around 2.4 per cent per annum. The number of jobs created in Australia’s renewable energy sector will be more than double the number of jobs lost from ending coal-fired electricity generation.

This next graph shows how the decarbonisation takes place in each sector of the economy.

The ClimateWorks report was one of 15 prepared for the UN Deep Decarbonisation Pathways Project that involves modelling teams from 15 major emitters that also include Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, the UK and the USA.

The findings are being presented to the UN this week by leading economist Jeffrey Sachs. It shows that these countries account for 70 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. The interim results show that all 15 countries found ways to achieve near zero carbon electricity by 2050, while sustaining economic growth.

This graph below shows how their electrify generation mix might vary, although some countries – such as the US and the UK, appear to rely heavily on CCS. Several rely heavily on nuclear, although France – the economy with the highest penetration of nuclear at the moment – almost completely flips its energy mix to rely more than two thirds on renewables.