Australia is the only country with a methane reduction target to make any progress in the last year, says climate data company Kayrros.

The Global Methane Pledge was launched at last year’s COP26 in the UK, with more than 100 countries promising to bring down methane emissions by 7 per cent a year and 30 per cent cumulatively by 2030.

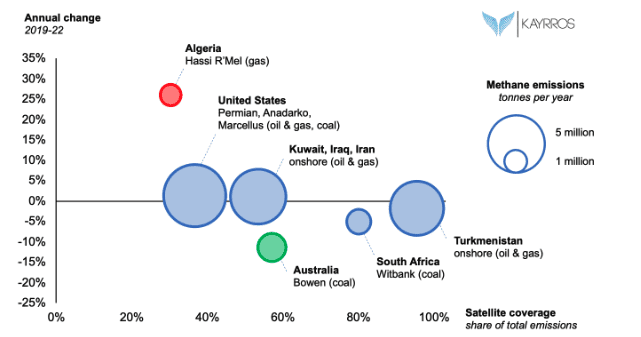

Kayrros data shows the only country to make headway on this pledge is Australia, thanks to a sharp reduction in methane coming off Bowen Basin coal mines.

It says in the last year methane emissions from the globe’s largest oil, gas and coal basins, which are responsible for a tenth of the world’s methane, were largely unchanged in the 2022 year to date compared to pre-COVID-19 levels.

Methane inventories in select fossil fuel basins (size of bubble = Mt CH4/yr), coverage of satellite data (x-axis, relative to total country emissions) and annual trend rate since 2019 (y-axis).

“Emissions from Australia’s Bowen basin have declined by approximately 11 per cent per annum,” Kayrros said in its pre-COP27 report.

“The encouraging trend in Australia’s Bowen basin likely reflects mitigation activities by mining companies. Reducing emissions from coal mining is based on well-known technologies that were originally developed to reduce the risk of underground explosions.

“Until recently, coal producers invested in these technologies only to address safety concerns.

“Now that methane from coal mining is in the spotlight among a growing number of investors and regulators, there is a business case to be made for reducing emissions beyond the level required by safety protocols. The implication for the rest of the energy industry is clear: mitigation is possible with the right incentives.”

The company uses data from the Sentinel-5P satellite of the European Space Agency to measure actuarial methane emissions by “super emitters” around the world.

While methane has a shorter lifespan in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, dissipating after about 12 years as opposed to 100, it also has 80 times the global heating potential, making it much more immediately destructive.

Methane super-emitters detected with Sentinel-5P since January 2019 and attributed to human activity.

Antoine Rostand, co-founder and president of Kayrros, said a lack of regulation and emissions controls are holding the world back from making progress on methane reductions.

“Improving satellite imaging technology has allowed for a granular understanding of these problems and better reporting of risk,” he said.

“This supports the industry in making more informed decisions, coupled with policy updates, notably with the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act and changes in key economies, to create the regulatory and financial incentives to accelerate abatement measures.”

But there is hope. Kayrros data, based on examples like that of the Bowen Basin, shows that with the right incentives all serious emitters can be “eliminated” by 2025 and the world could even exceed Global Methane Pledge commitments by 2030.

The US’ Inflation Reduction Act is set to provide a roadmap for other countries around incentives for businesses to modernise infrastructure and improve practices, Rostand said.

Paying for past climate-related liabilities

Methane won’t be the only issue making life uncomfortable for developed nations at COP27.

Formalising a fund for loss and damage is set to be a key issue. It was one of the main reasons why African nations nominated Egypt — a COP host choice roundly criticised by human rights groups — to steward this year’s conference, because of its strong advocacy stance on loss and damage.

Loss and damage finance, or cash aid that directly addresses unavoidable climate change catastrophes such as rebuilding homes and hospitals after a disaster, something developing nations are particularly vulnerable to financial losses from.

It was a key request from a coalition of developing countries in Glasgow last year.

But after hard pushback by the EU and the US, which want to limit wording around liabilities for past emissions, this issue was effectively scrubbed from the final communique and the issue relegated to a newly created Glasgow Dialogue on Loss and Damage, set to run until 2024.

However, advocate for loss and damage financing, such as the Climate Council in Australia, hope the sixth International Panel on Climate Change (IPPC) report, which specifically called out loss and damage as an emerging area that needs to be addressed, will make it more difficult for developed nations to ignore the issue.

To date Canada, Denmark, Germany, New Zealand and Scotland have indicated they’re willing to support financing for loss and damage.

Australia wants COP31

Australia, with its newly rejuvenated climate policy attitude, is pushing to host the 2026 COP conference.

Last week the government reinstated the position of ambassador for climate change, naming DFAT secretary Kristin Tilley to the role. Her job will be to demonstrate to the world that Australia’s new resolve is genuine and to alongside partners, particularly in the Pacific, on climate change issues.

Tilley, alongside energy minister Chris Bowen and international development and the Pacific minister Pat Conroy, are at the 27th Conference of the Parties (COP27) in Egypt, selling the government’s new policies of a 43 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030, up from 26 per cent, and net zero by 2050.

Those government ministers emphasised Australia’s new position of helping Pacific neighbours deal with the climate emergency, and Bowen will also be selling the story of renewable energy exports and “green trade partnerships” as the way to meet climate change objectives.

Joining the 100 (billion) club again

The pressure is on Australia to do more, however, such as rejoin the UN’s $US100 billion ($A155.6 billion) Green Climate Fund.

Australia left the fund in 2018, opting instead to provide bilateral climate-related funding and aid.

Think tanks such as the Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue (AP4D), are calling for the country to rejoin the UN fund, and the Climate Council and Oxfam are arguing for Australia to boost its annual budget for developing countries to $3 billion or more.

COP27 is expected to see pressure put on developed countries to fill their pledges to the climate fund which has been effectively ignored since developing countries made the commitment in Montreal at the 2009 COP15.

A study by Oxfam in October last year showed that a massive shortfall risks sending developing country nations into an unprecedented debt-trap.

“Current pledges up to 2025 will leave low-income countries up to $US75 billion out of pocket. This finance shortfall is unfairly pushing the costs of the climate crisis on to those least responsible for it,” the report said.

Oxfam estimates Australia’s fair share at 2.5 per cent of global climate action, or a total of $4 billion now and rising to $12 billion annually by 2030.