Australia could source 86 per cent of its electricity from wind and solar by 2050, based on economics only and regardless of any climate or emissions policy, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

The global research and news group says that level of wind and solar could be reached quicker, and will need to in order to match the Paris climate target of 2°C, let alone 1.5°C, but the transition to wind and solar is inevitable.

That’s because, according to BNEF’s Seb Henbest, wind and solar already provide the cheapest source of bulk energy for new generation, and will soon beat most existing fossil fuel plants on the same criteria.

Even with the significant amount of “curtailment” and storage that would be needed in such a scenario, a grid based around such high levels of wind and solar will still be cheaper than the alternative.

“This is not a prediction based on policy, just economics,” Henbest says in an interview with RenewEconomy ahead of a presentation of BNEF’s New Energy Outlook in Sydney on Tuesday.

Henbest says Australia will be part of a global transition, but would likely lead it because of its extraordinary wind and solar resources.

BNEF’s headline conclusion in its New Energy Outlook is that the world will be at 50 per cent wind and solar by 2050 – although, in effect, its analysis shows 48 per cent, but it couldn’t resist the “50 by 50” line. Total renewables by then will be at 64 per cent.

Australia will be a leader, but the UK (80%), Spain and Portugal (78%), Italy (78%), Germany (74%), Mexico (72%) and even France (72%), yes now nuclear dependent France, will sources more than 70 per cent of their electricity from wind and solar by 2050.

India, Philippines and Japan will source more than 60 per cent. The global average is brought down by the US (45%, coal is gone, but lots of gas), China, Russia and the Middle East.

Henbest says such a high level of wind and solar will require a whole new way of thinking about the grid. “Back-up and curtailment will be a feature, not a bug, of the future energy system,” he says.

“If you have lots of wind and solar – dispatch is no longer as predictable, it’s not as straight forward as in a world where generators are running almost at the same output all the time.”

It means that on some days there will be more energy produced in a single day than can be used – so there will be storage, and curtailment. On other days, there will be not enough, so back-up is required, either through that storage or the remaining fossil fuel (gas) dispatchable plants.

But Henbest underlines the importance of a change in thinking towards flexibility and dispatchability, rather than the traditional mindset of base-load and peak-load.

Right now, he suggests, even in Australia with levels of wind and solar up around 50 per cent in some areas, such as South Australia, it is still considered to be a fossil fuel grid with wind and solar as an addition. That needs to change.

This observation points to some of the political debate around energy now, and the strong attachment among conservatives to the idea of new coal-fired generators being built. Not because they are economic, although many are convinced they are, but because they preserve the fossil fuel vision of grids.

“If we recognised and removed the barriers, and did not lock in fossil fuels, then Australia will likely transition more quickly,” he says. And it would most certainly do so with targets that encourage and facilitated that transition.

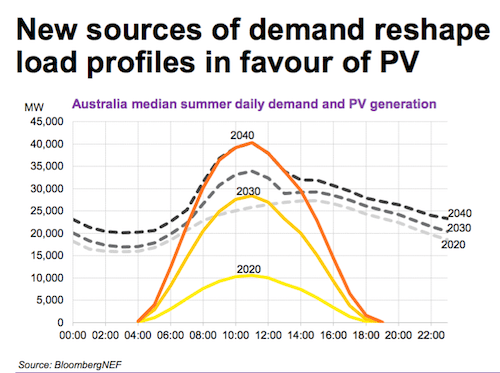

Henbest says Australia will likely have a huge amount of capacity and generation and storage “behind the meter” and located in households and businesses – some 67GW of rooftop solar and around 60GWh of battery storage.

It will be a highly distributed system, with 40 per cent coming from the point of consumption – a target similar, although slightly undershooting, expectations from the Australian Energy Market Operator.

“This is likely to happen in the absence of government (policy),” Henbest says. “This is not just a function of tariffs.”

By 2050, there will be no coal, and just a small amount of gas – used less often but around the same capacity, unless alternatives like hydrogen and other technologies can deliver it more cheaply.

Utility-scale batteries will beat gas relatively soon for short peaks (see graph above), although hydrogen gas or another will be needed for seasonal storage.

There are no barriers in terms of land area or network capability. Energy market design will be critical, and Henbest notes that all governments will need to look, like Australia, at combining the needs of emissions and reliability.

He says the proposed National Energy Guarantee does that, although how it ends up with the final design – and whether the structure of the climate targets are appropriate – will depend on political outcomes.

For the moment, however, he says it has no bite. Like other independent analysis, BloombergNEF concludes that the current emissions targets mean that there will be no acceleration in the uptake of wind and solar.

And here’s the bad news. Even with BloombeNEF’s optimistic transition forecasts based on economics, the world still fails to get anywhere near the pace of change needed to honour the 2°C target in the Paris climate treaty, let alone the aspirational goal of limiting average warming to 1.5°C.

“There is a big gulf between the 2°C trajectory and where power emissions end up,” Henbest says. “That because there is simply too much coal in the system, and gas (if it was to replace coal) is too carbon intensive.

“So you need policy drivers to get (to the 2°C) target. Country by country you get a different story, but you do need a vision of what the new energy system looks like. And (politically) that’s very difficult.”

He notes that the private sector needs to recognise that the “writing is on the wall” and help pick out the strategy of how to win out in a new world.

(Some of that is happening in Australia, where the likes of Sanjeev Gupta and others are turning to solar and storage, while the likes of the Business Council of Australia preach disaster if the share of renewables exceeds 28 per cent).

“We do need active policy intervention to visualise the future system and put regulations and rules in place to get there,” Henbest says.

“Business as usual will not get us there in time, because there are complications with network problems, market rules, investment decisions.

“Do we need to incentives for solar because they are expensive? No. Do we need to provide a signal that recognises value to solar, yes we do. Same with batteries.

“To pay for back up and curtailment you need to think about price signals in a sophisticated way.

“How does private and the public system work together? This is not a hands-off policy situation. Getting the cheap stuff into the market looks very disruptive … and that’s the challenge.

“This is a global technology shift – and it will happen. Part of it is the rate of change, part of it is the facilitation.”