The amount of large-scale solar and wind capacity added to energy systems around the world grew by 50% in 2023, setting a faster pace of global renewables growth than at any time in the last three decades and putting the world on track – almost – to meet the COP 28 goal of tripling capacity by 2030.

The latest analysis of the renewables year that was by the International Energy Agency, and its forecast out to 2028, says the the world added almost 510 gigawatts (GW) of new renewable energy capacity, a huge three-quarters of which was solar PV.

And looking forward, the IEA’s Renewables 2023 report forecasts that global capacity will grow to 7300GW over the 2023-28 period under existing policies and market conditions, including the plummeting cost of solar PV.

In 2023, the report says, three-quarters of newly installed solar PV and onshore wind capacity offered cheaper power generation than existing fossil fuel facilities. Only offshore wind remains outside that realm.

By 2028, the IEA estimates that more than 80% of newly installed variable renewable capacity will provide electricity more affordably than existing fossil fuel alternatives. Even offshore wind, by then, could be more economically attractive than new coal plants in China, the report says.

Solar and wind are expected to account for 95% of the growth over the 2023-28 period, the IEA says, with renewables overtaking coal to become the largest source of global electricity generation within just a year’s time, by early 2025.

Still, however, we are not moving fast enough.

“The new IEA report shows that under current policies and market conditions, global renewable capacity is already on course to increase by two-and-a-half times by 2030,” said IEA executive director Fatih Birol.

“It’s not enough yet to reach the COP28 goal of tripling renewables, but we’re moving closer.”

And some countries, in particular – including Australia – need to stop dragging their heels.

The IEA lists Australia among a handful of countries that have had their forecast growth rates “reined in” in this year’s outlook, due to a range of speed humps including ongoing policy uncertainty around large-scale renewables and a failure to keep up regulatory and logistical pace with the huge growth of rooftop solar.

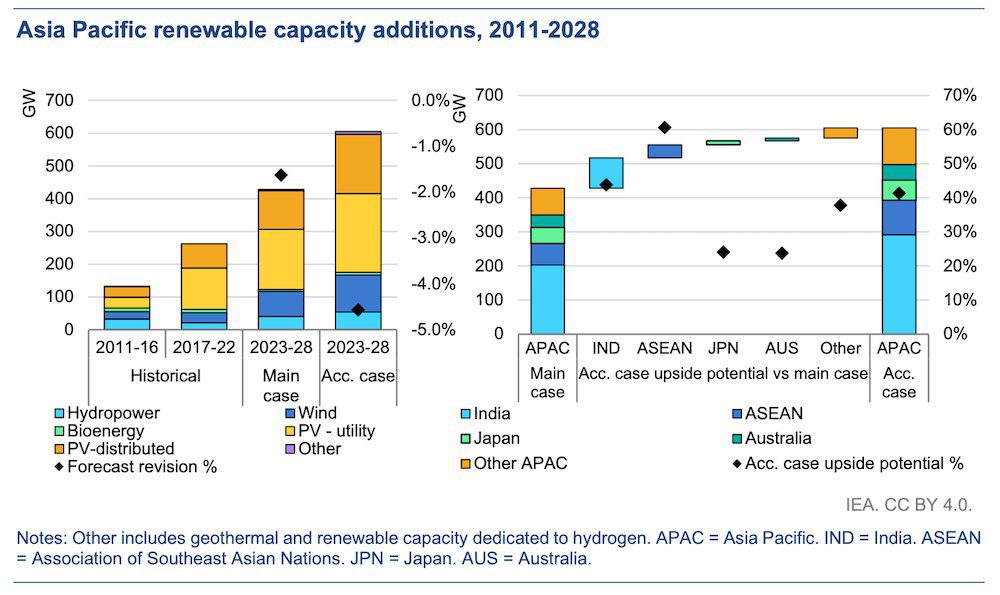

While renewable capacity in the Asia Pacific region is expected to increase by almost 430GW over 2023-2028 – 73% growth from 2022, the IEA revises down Australia’s projected growth rate by over 10%.

“A lack of new federal incentives and rising investment costs have delayed the development of new projects,” the report says.

“Notably, the distributed PV segment, which has been the primary source of growth in Australia in recent years, is forecast to experience a faster-than-anticipated decline in installations due to saturation of the power system and increasing grid integration challenges.”

The report goes on to say that in the developed countries of the region, like Australia, overcoming grid bottlenecks, streamlining lengthy permitting processes and enhancing system flexibility should be prioritised to gets growth back up to speed.

“Grid queues are growing and investment is lagging, leading to longer lead times and higher costs,” it says.

“Even projects nearing completion can still be subject to delays: In Australia for instance, commissioning processes can be a year or longer.”

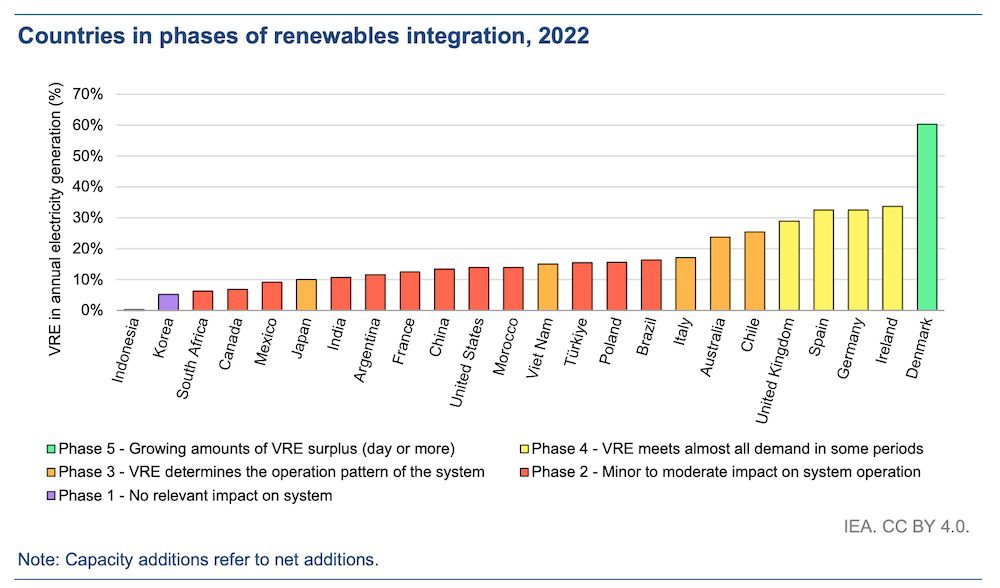

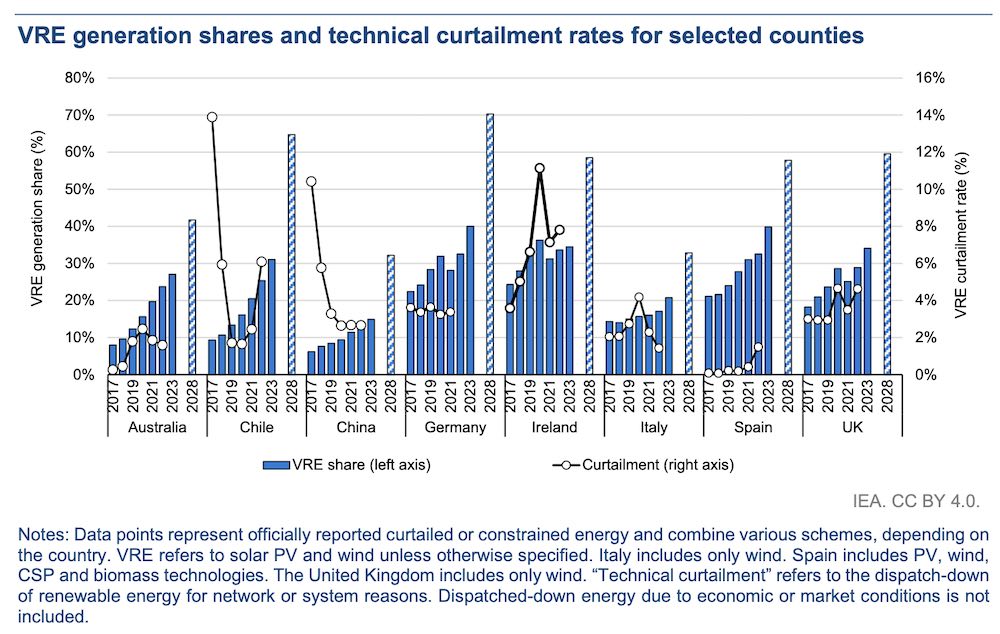

Policy makers are also called on by the IEA to address the growing problem of solar and wind energy curtailment, on grids that – like Australia’s – are struggling to keep up the pace with the shift to renewables, and particularly huge amounts of daytime solar boosted by rooftop PV.

“Naturally, curtailment rates are higher in regions that need substantial grid infrastructure expansion to connect renewable energy installations to consumption centres,” the report says.

“Effective system planning is thus crucial for well-integrated wind and solar PV growth and should encompass considerations such as the regional distribution of generation and the development of policies to encourage system flexibility.”

Also flagged as a dark cloud over future renewables progress is the hydrogen project development lag that is playing out around the world – and for this, too, Australia gets a dishonourable mention.

The IEA says that according to its Hydrogen Projects Database, there are over 360GW of electrolyser projects using dedicated renewable electricity capacity with announced start dates before 2030 in the development pipeline at various stages.

“However at the time of writing, only 3% (12 GW) of them had reached financial close or started construction, a smaller amount than expected in our Renewables 2022 forecast,” the report says.

“Some of the planned projects in the Renewables 2022 forecast have had no updates over the last year or have been cancelled completely.

“The forecast is also less optimistic for Asia-Pacific, mostly due to uncertainty in Australia over the future of stalled projects,” it continues.

“One project’s environmental permit had lapsed before it reached financial close, and plans for projects in Bell Bay have been put on hold due to high water and transmission congestion.”

Birol says that while current global growth rates are not yet enough to reach the COP28 goal, “governments have the tools needed to close the gap.”

Policy, for one, will be key; the report forecasts that roughly 87% of global renewable utility-scale capacity growth in 2023-2028 is expected to be stimulated by policy schemes.

In countries like the US and Australia, where existing coal power – and fossil fuel influence – is still dominant in many key regions, policy will be crucial in tipping investment away from coal and gas and towards renewables.

“We are increasingly on track not only for a peaking of fossil fuel use this decade, but for sizable falls in fossil fuel use,” says Dave Jones, a program director at global energy think tank Ember.

“This is at odds with the huge investment planned by the oil and gas industry, fuelled by the superprofits of the energy crisis, which is creating a chasm between outlook for demand and the outlook for supply.

“2024 will be the year that renewables changed from a nuisance for the fossil fuel industry, to an existential threat,” Jones says.

“In most parts of the world, governments need to get serious and roll their sleeves up when it comes to creating the policy settings for the energy transition,” says Global Wind Energy Council CEO Ben Backwell.

“Policymakers must work hand-in-hand with the wind industry, and offshore wind in particular, on creating attractive investment environments, faster permitting procedures, sustainable supply chains and grid integration plans.

“Given today’s difficult macroeconomic environment, especially for developing countries, supportive policy for the wind sector is more important than ever,” Backwell said.

“The IEA report makes it clear that energy policy is holding back the energy transition – not technology, not costs and certainly not ambition,” says Joyce Lee, the Global Wind Energy Council’s head of policy

“Tripling renewables is in the realm of the possible. But it will require urgent and decisive policy adjustments to accelerate wind project permitting, put big volumes forward for auction, incentivise investment in sustainable supply chains, and build out the critical grid infrastructure needed to deliver clean electricity to homes.

“Amidst rising inflation and higher cost of capital, policymakers and financial institutions must also step up their collaboration with the industry to create attractive project investment environments, especially in the Global South.”