Two new reports from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency and a group led by chief scientist Alan Finkel have highlighted the enormous opportunities for Australia in pursuing “green” hydrogen exports, based around the country’s enormous potential for wind and solar power.

The reports include the possibility that coal could deliver a similar outcome, but given the uncertainty and cost of carbon capture and storage, and the plunging cost profiles of both wind and solar, it seems inevitable that any hydrogen export industry will be based around renewables.

Several small-scale hydrogen facilities have been commission in Australia – in South Australia and the ACT – but these are mostly focused on transport solutions or smaller scale electricity storage.

Both the ARENA and the Finkel reports are focusing on much bigger ideas, the potential replacement of Australia’s massive LNG export business, for instance, by “green gas”, satisfying the emerging huge demand in east Asia in particular for emissions free fuels.

The ARENA report, prepared by consultants ACIL Allen – the same outfit that had to do the NEG modelling based on the sorry inputs of the Energy Security Board – highlights that this is a long term play, but with enormous potential.

According to the various scenarios, the hydrogen export market could grow from a low growth scenario of 26,000 tonnes in 2025 to 621,000 tonnes by 2040, to a high growth scenario of 3.2 million tonnes by 2040. The bulk of this would go to Japan, with Korea and China following.

The report from the Hydrogen Strategy Group, chaired by Finkel, also identifies Japan as the key market, given its big switch away from nuclear post Fukushima, and the lack of renewable options at home.

“I ask myself “why now?” given that the idea of a hydrogen economy has been seriously and frequently proposed since 1972,” Finkel writes in a letter to CoAG.

“The answer is Japan’s commitment to be a large-scale enduring customer, and the hundredfold reduction in the price of solar electricity in the past four decades.”

As we reported earlier this week, Finkel gave a 10 minute presentation to CoAG last Friday that was well received and ask to return in December with a detailed plan of action. His plan includes a bigger focus on domestic hydrogen opportunities, for generation, storage and transport.

The implications for Australian generation are enormous. In the ARENA report, even in a medium scenario, they amount of new generation needed by 2030 would be 31,000GWh – almost equivalent to the current renewable energy target.

The amount of new generation for the high scenario is double that – 68THW (68,000GWh) by 2030 and by 2040 is 200TWh (200,00GWh) – equivalent to the annual output of the entire National Electricity Market.

“It is important to provide a perspective of the scale of this potential export opportunity,” the study notes.

“If we assume an efficiency of around 50 per cent for the steps from electrolysis through to liquefaction, this implies an additional electricity demand of between 1 TWh (2025 low demand scenario) and 200 TWh (2040 high hydrogen demand scenario).

“The 200 TWh in 2040 is more than the entire current generation of the NEM. The potential export of around 60 PJ (502 kilo tonnes) in the medium scenario in 2030 implies an additional demand of around 33 TWh, which is equivalent to the amount of Australia’s Large-scale Renewable Energy Target.”

And it is highly likely that this new generation will come from renewables, rather than coal, although the reports, and ARENA’s in particular, tend to downplay that aspect – given the toxic politics in Canberra over everything renewable and the design of the NEG, which models zero investment in wind and solar over the next decade.

The reality is, however, that wind and solar offer the cheapest source of bulk energy, which is what is needed for hydrogen, and coal is not only more costly is has significant emissions issues.

Just look at the recent brown coal hydrogen pilot project announced for the Latrobe valley – $500 million to produce just three (3) tonnes of hydrogen, and they are not even sure they can sequester it.

“Countries around the world are under increasing pressure to decarbonise their economies,” the report notes. “There is growing interest in the production and use of hydrogen as a potential scalable and versatile mechanism for achieving this aim.”

And on energy sources, it notes:

And on energy sources, it notes:

“It is most likely that the facilities will be located close to the supply of renewable energy, and quotes the recent CSIRO roadmap which suggests the cost of renewables will be around 4c/kWh – and the cost of energy makes up 75 per cent of the cost of hydrogen.

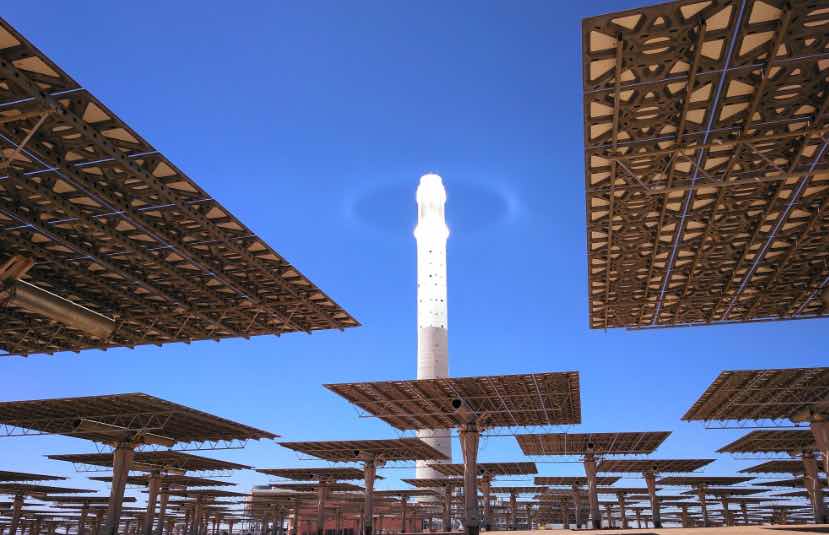

“Renewables, particularly large scale solar PV or concentrated solar thermal projects are most likely to be located where the solar irradiance is high in Australia. Such areas of high solar irradiance (and reasonable ease of access to appropriately sized areas of land).”

‘Hydrogen production for export may therefore particularly benefit regional communities, traditional owners of the land, and the broader Australian community through the direct employment associated with hydrogen production facilities.”

The Finkel report highlights the opportunities for Tasmania and South Australian in particular. Of the latter, it notes:

The Finkel report highlights the opportunities for Tasmania and South Australian in particular. Of the latter, it notes:

“South Australia, now a global test bed for various new energy technologies, has hydrogen demonstration projects in the pipeline. Its high proportion of solar and wind electricity makes it an attractive location to invest in hydrogen production and associated industries.”

The renewables industry is not the only one excited by the prospect of the hydrogen economy, the networks lobby, particularly those who have invested heavily in gas networks, are also keen.

It says hydrogen can be safely added to natural gas supplies at up to 10 per cent by volume without changes to pipelines, appliances or regulations.

“From a gas distributor’s perspective, hydrogen has potential to support electricity and gas networks by allowing renewable hydrogen to be stored in existing infrastructure and then be used for providing heat or generating electricity,” ENA head Andrew Dillon said.

“The storage capability of our existing gas networks is enormous, with the equivalent of six billion Tesla Powerwall batteries already in place.

“Over time, the gas networks will be able to deliver 100 per cent hydrogen as a replacement for natural gas for domestic cooking, heating and hot water.” Dillon said using renewables to generate hydrogen also creates new revenue raising opportunities for solar PV and wind generation.