It was not the worst welcoming gift for the Labor government, whose thumping election win last weekend has laid out what they will inevitably present as a strong mandate to do what needs to be done to achieve their climate targets.

Chief among those targets is an ambition that is genuinely difficult: running Australia’s National Electricity Market – the NEM – on 82% non-fossil energy (wind, solar and hydro, enabled by new transmission lines, lithium-ion battery storage and some new hydro).

AEMO’s latest quarterly report – released this week – reveals some genuinely reassuring signs of continued progress in pushing down fossil fuel combustion – and greenhouse gas emissions – in the NEM.

What stands out to me the most is the return of wind – a technology that has globally seen stumbles, bumps and complications while solar has not. While shifts in the pricing dynamic of the grid continued to fluctuate, the system continues to manage rising shares of variable renewable energy – particularly growing shares of solar peaking in the middle of the day.

“The Q1 2025 VRE increases for Victoria of 351 MW (+27%) and New South Wales of 319 MW (+19%) made up 87% of the overall increase from Q1 2024 (Figure 44),” the report says. “Growth in wind output was most significant in Victoria, up by an average of 275 MW (+26%) while for grid-scale solar, New South Wales recorded the largest increase from Q1 2024, with average growth of 141 MW (+14%).”

AEMO’s report also highlights the complexities of integration, not just of ensuring reliability and reducing cost, but of seizing on the maximum possible volume of available wind and solar resources. While utility-scale solar rose by 321 ‘available’ megawatts, there was only a 221 megawatt increase in actual solar output. So 100 MW were lost to ‘economic offloading’ (ie, choosing not to generate during lower price periods) and network constraints. It is a dual story of continued solar growth paired with significant new limitations.

New capacity at several large wind farms, ranging from around 40 to 70 megawatts per project, saw a similar rise in ‘available’ wind output of around 417 megawatts, but similarly, ‘economic offloading’ and network congestion shaved the edge. Operators of wind and solar projects withholding generation because the price of power is simply too low to make it worthwhile – or negative – is becoming noticeably more common:

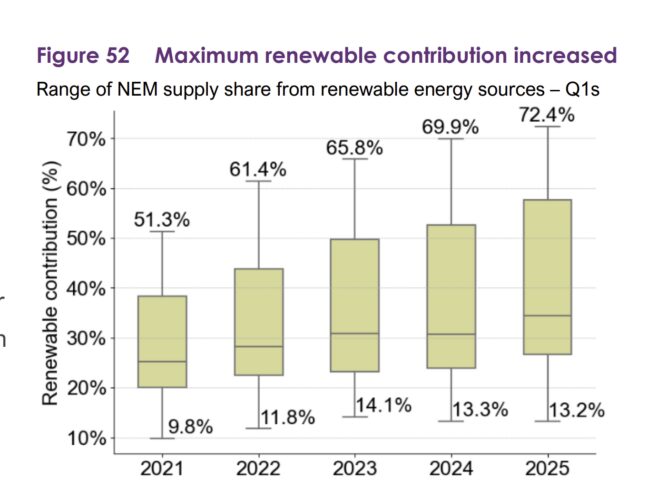

AEMO faces a near future where flexibility will be key. You can see this the graphic they provide of the variation in renewable contribution. The ‘maximum’ of renewable contribution continues to rise, but notably, the minimum stays relatively similar over the past three years. What this means is a deeper need for resources that can manage a system that operates in vastly different states between different times – namely, resources like batteries or hydro storage.

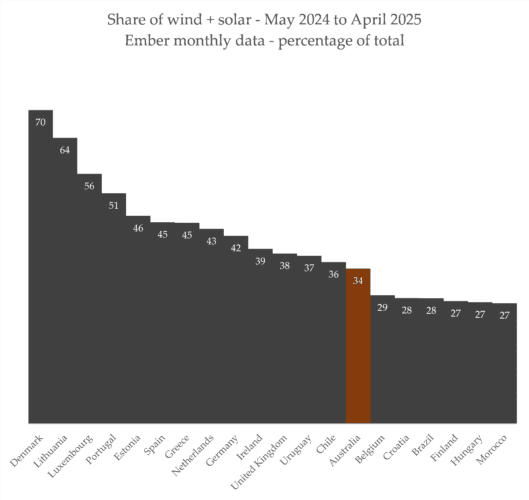

Australia is part of a club of countries with relatively large grids seeing very high volumes of new wind and solar rapidly displacing coal and gas generation.

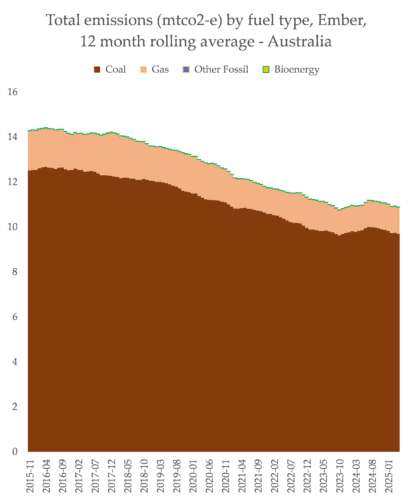

Despite the narratives of gas as a ‘transition fuel’, the AEMO report finds that gas saw its lowest Q1 level since 2004. Whatever’s being done to integrate wind and solar into Australia’s grid, it does not involve burning increasing volume of fossil gas – which makes AEMO’s own calls for opening up new gas fields to increase supply somewhat awkward.

Paired with the reduction in coal output, this brought emissions to a record low – a low that would have been far, far lower without the notable constraints applied to wind and solar generation.

If this trend continues, there is a decent chance Australia will get back on track. But as Giles Parkinson wrote here recently, there is some hesitancy to consider forms of renewable energy integration that don’t involve the procurements of large, heavy spinning masses.

More contemporary forms of technological grid integration, including technologies that can deal with a range of grid services beyond fast frequency response are becoming increasingly available.

Renewable energy integration is not just about plug-and-play – it is about maximising the use of the machines installed to convert flow resources like sun and wind into electricity, including capturing that as stored energy to shift its use in various other parts of the day.

AEMO details a vast quantity of curtailment being both mandatorily applied but also financially induced among non-fossil power generators – it seems like a strange thing to allow when we know the harms of allowing power generation from fossil fuels.

It’s clear from AEMO’s report that a good chunk of this challenge is going to involve not just the grind of new wind and solar construction, but some more fundamental transformations within the philosophy of the world’s biggest machine. Once that mindset changes, fully eliminating fossil fuels from power grids becomes more realistic.