It’s official. After a decade of delays, protests and acrimonious debate, followed by two years of expensive construction work, Indian conglomerate Adani has finally got its hands on some actual Queensland coal.

“It is wonderful that we have now struck coal,” David Boshoff, chief executive of Adani’s Australian mining operations, said on Thursday.

“Throughout the last two years of construction and during the many years when we fought to secure our approvals, our people have put their hearts and souls into this project.”

The announcement came with a photo of nine smiling mine workers, each holding an enormous lump of black thermal coal, 10 million tonnes a year of which is destined to be shipped out of the Abbot Point coal terminal and burned thousands of kilometres away in Indian power plants.

In the process, the mine will provide 2600 local jobs and add somewhere in the region of 20 million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year to the atmosphere, doing its bit to push up global temperatures past a dangerous point of no return.

Thursday also happened to be billionaire boss Gautam Adani’s 59th birthday. To mark the occasion, two mine workers sent a birthday video message to their “dear chairman” back in India, one of them cradling a lump of Carmichael coal in his arms, thanking the tycoon for his “resilience”. Adani himself tweeted in response that “there couldn’t be a better birthday gift.”

Proud of my tenacious team who mined Carmichael’s ‘first coal’ in the face of heavy odds. There couldn’t be a better birthday gift than being able to strengthen our nation’s energy security and provide affordable power to India’s millions. Thank you, Queensland and Australia. pic.twitter.com/NbHLccLZko

— Gautam Adani (@gautam_adani) June 24, 2021

But does the world even want or need this coal? Eleven years on from Adani’s original investment decision, the global energy landscape has changed beyond recognition. Renewables are now, out and away, the cheapest form of new energy. Nations are taking climate change ever more seriously, committing to ambitious targets that will require a rapid phase-out of coal. And global investors increasingly want nothing to do with this most climate polluting of fossil fuels.

Future demand for coal, in other words, could hardly be more uncertain, and the Adani Carmichael mine looks more than ever like a massive stranded asset.

Adani’s own figures reflect this. In 2010, the plan was to export 60 million tonnes of coal a year from the mine, mostly back to India, and the hope was that it would be open for the best part of a century. Now, the planned export figure is 10 million tonnes a year, and the lifetime of the mine will likely be two or three decades, at best.

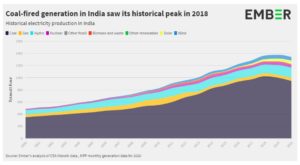

Adani struck coal the same day UK think-tank Ember released a new report arguing India may have already reached peak coal demand. It also came the same day BloombergNEF published a new report finding it was now cheaper to build new solar farms in India than it was to keep existing thermal coal plants open.

Meanwhile, the constant stream of investors and insurers ruling out involvement in the project has continued, with Samsung announcing it had divested from Adani Ports, the subsidiary that runs the Abbot Point coal terminal – an asset that is becoming an increasing headache for the Indian conglomerate.

“Samsung Asset Management India Mutual Fund had sold Adani Ports shares due to recent market noise and share price volatility related to Adani Group’s coal project,” the South Korean conglomerate said in an email to campaign group Market Forces.

“[T]herefore as of June 23, 2021 the fund no longer owns Adani Ports shares and has no plan to repurchase the shares.”

Meanwhile, a $1 billion loan to the Carmichael project from the State Bank of India, first flagged last December, is yet to come through, and there are questions over whether it ever will, thanks to pressure from powerful investors including BlackRock, Allianz and Pimco.

Tim Buckley, a director of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) and an expert on Indian energy markets, says the Carmichael mine is now the “epitome of a stranded asset”.

“It will never make viable returns. It’s unsaleable. It’s a decade behind schedule, a couple of billion dollars over the expected cost, and it is one-sixth of the size of the original proposal,” he says.

IEEFA estimates India will reach peak coal generation in 2025. The International Energy Agency agrees. Ember argues it will come earlier than that – and may, in fact, have already peaked. Buckley says the exact date is academic. The point is everyone, including the Indian government, agrees that coal demand is only headed in one direction, long-term.

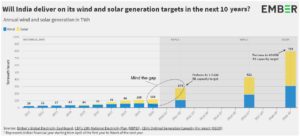

The rate of growth in renewables, meanwhile, is gathering pace. On Thursday, Asian energy giant Reliance announced it would build an astonishing 100 gigawatts of new renewable capacity in India by 2030, in an effort to help meet the Indian government’s stated goal of building 450GW of renewable capacity by 2030.

Earlier in the week, India’s biggest utilities company, NTPC Limited, doubled its target for renewable capacity from 32GW to 60GW by 2032.

However, as the chart below from Ember shows, to meet the 450GW goal will require a step change in India’s current rate of renewable construction.

Even if India is successful in this, demand for coal-fired electricity will not stop altogether any time soon. But Buckley says as renewable capacity grows, coal will be used more for peaking than as baseload power.

Currently India sources about 600 million tonnes a year of coal domestically, and a further 200 million from overseas. As demand for coal falls, India is aiming to meet more of its demand from domestic supply. That means cutting its international supply in half.

If Adani wants a growing market for coal, then it needs to find another use for it – and using it as a feedstock to make plastic products is one possibility.

Earlier this month Adani announced it was investing $US4 billion in a new plant in the Indian state of Gujarat that will turn coal into PVC. That part of India is not close to any domestic coal mines, so it was seen as a plan to make use, at least in part, of the Carmichael coal. Adani denied this, saying “the coal from the Carmichael Project in Australia is not suitable for the PVC plant”. Adani’s line is that it will be used in Indian power plants.

Given all of these problems and uncertainties, it seems sensible to ask why on earth Adani has persisted in developing a mine that seems so obviously unviable. Buckley says the main answer to this is the company’s decision a decade ago to invest $2 billion in purchasing the Abbot Point coal terminal on a 99-year lease – a transaction that was entirely financed by debt. The port is currently operating only at about 55 per cent capacity, which is insufficient to meet the huge interest payments on the loans. Adani’s difficulty in refinancing this debt has been well publicised.

“They’ve invested $5 billion in a stranded asset, and the only reason they are going ahead is they’ve got a coal port that they bought for $2 billion from the Queensland government, and they’ve got to pay the interest on it,” says Buckley. “Even if you’re a billionaire, you’ve got to open the mine so you can start paying some of that interest.”