A tipping point is about to be reached in the shift to electric vehicles from the internal combustion engine. Tesla has secured unprecedented orders for its Model 3, India wants petrol cars off the road by 2030, Norway wants them gone by 2025 and the Dutch want only EVs for sale by 2025; others say that will be the only choice by then, in any case.

In Australia, however, the EV market is so small it is barely visible, apart from the growing number of $124,000-plus Tesla Model S vehicles sported by the wealthy.

Not only does Australia have few EVs, it has no emissions standards for vehicles, and few if any incentives to encourage people to drive cars that cause less pollution.

So, a consortium of utilities, electric vehicle suppliers, city councils and research groups want the Australian government to get serious about the issue. They say there are six reasons why this is a good idea.

EVs will increase fuel security:

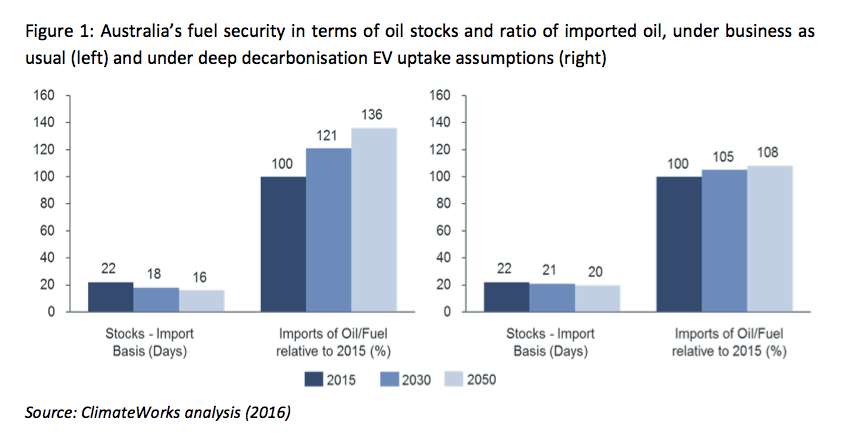

Australia imports increasing amount of fuels for its transport needs. Imports now account for 90 per cent of our fuel needs, leaving barely three weeks of supply in case of a crisis. That is despite Australia being a signatory to the International Energy Program (IEP) Treaty, which has a requirement to hold the equivalent of 90 days of the previous year’s net imports.

Not only that, imports are expensive, as Professor Ray Wills pointed out the other day, they account for more than $2 billion a month.

EVs will reduce emissions:

There is much debate about whether EVs do in fact reduce emissions in a country so heavily reliant on coal for its electricity.

ClimateWorks says that, on average, using the National Electricity Market to charge electric cars does reduce emissions. (The exception is Victoria with its brown coal dependency, but Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia deliver significant savings).

Its study says that if the renewable energy target is met, then by 2020, those savings will be greater, and even more so if Australia pursues the “deep carbonisation” that it has signed up for at the Paris climate talks.

EVs will deliver health benefits:

A 2011 study suggested significant uptake of EVs in Victoria would reduce emissions by nearly 1.5 MtCO2e in 2030 as part of $5.5 billion in wider economic benefits for the Victorian economy.

That study also highlights the air quality benefits arising from electric vehicle adoption, delivering air pollutant reductions of almost 10,000 tonnes of NOx and 2,000 tonnes of PM10. According to EPA Victoria, these figures represent around 10 per cent of the 2006 inventories for these pollutants in the Port Phillip region.

CSIRO modelling from 2012 found that electric vehicle adoption would be concentrated in metropolitan areas of Victoria, where population densities were at their highest. When it is considered that the impact of air pollution on human health depends on where the pollution is, in relation to where people are located, electric vehicle uptake has the potential to deliver meaningful benefits to community health.

EVs will provide more job opportunities:

Increased uptake of EVs within Australia also presents a potential opportunity to increase local employment opportunities. Employment will be created potentially through sales, charging infrastructure deployment, and potential opportunities to create new manufacturing jobs specialising in batteries, EV components or charging infrastructure technologies. There will also be potential increased employment and economic benefits from the increased demand for locally produced electricity, replacing the predominantly imported petroleum-based fuels.

EVs will improve consumer choice:

In Australia there is currently a limited number of models available, and the highest selling electric vehicles from international markets, including the Nissan LEAF Gen 2, Chevrolet Volt and Bolt (not being built in right hand drive), and Renault ZOE are not available in Australia. Nissan Australia CEO Richard Emery has previously stated that manufacturers need “government help, the same kind of assistance that governments in Europe, the USA and Japan provide” to overcome barriers to EV uptake in Australia and increase model availability.

That means that in an intensely competitive market containing over 400 passenger and light commercial vehicle options, there are a mere 14 plug-in makes/models. This means that for the overwhelming majority of Australian buyers, plug-in vehicles are not even available. Without choice and competition, prices won’t come down. European countries have addressed this by requiring EVs to make up a significant portion of fleet numbers.

And EVs will be cheaper

The ClimateWorks study noted that economic viability remains the most serious barrier and source of uncertainty in projections about the EV market.

“The difficulty for forecasting uptake lies in the chicken and egg paradox; electric vehicles will be cost competitive when scale in manufacturing is reached, however large-scale consumer uptake will only occur when electric vehicles are cost competitive.”

It says incentives have been used to overcome this conundrum in other countries, and has worked to achieve an increase in global electric vehicle production by 50 per cent to 300,000 per annum in 2014.

If Australia were able to achieve a 50 per cent improvement on fuel economy for new light vehicles over 10 years, equating to 130 gCO2/km in 2020, and 95 gCO2/km in 2025, there would be financial benefit to consumers through reduced fuel bills.

ClimateWorks’ analysis shows that net annual savings of approximately $350 for average drivers of conventional internal combustion engine vehicles over a five-year ownership period could be achieved, and economy-wide these fuels savings would total almost $8 billion per year by 2025. For electric vehicles however, higher cost savings can be achieved over the life of the vehicle due to increased fuel savings.

It says without action, on either EV uptake or CO2 emission standards, Australia runs the risk of becoming the dumping ground for low-specification models and falling further behind international peers, resulting in relatively higher fuel costs for motorists and businesses.