Governor Jerry Brown is an impatient man. In late April 2015, he signed an executive order to reduce statewide greenhouse gas emissions to 40% below 1990 level by 2030. In 2006, the state passed a law to reduce its emissions 20% below 1990 level by 2020, and 80% below 1990 level by 2050 (graph below).

But that was not enough. In early Oct 2015 he signed Senate Bill 350 (SB 350) to increase the percentage of new renewables in the electricity to 50% also by 2030 – the current law requires 33% by 2020 – which the state is on target to achieve or possibly exceed.

These and a number of other ambitious initiatives passed over the past few years are overlapping and occasionally duplicating, with deadlines that are not necessarily coordinated.

These and a number of other ambitious initiatives passed over the past few years are overlapping and occasionally duplicating, with deadlines that are not necessarily coordinated.

Moreover, different agencies are responsible for meeting the targets – without specific provisions on coordination, collaboration or liaison among them.

The California Air Resource Board (CARB), for example, is in charge of the climate bill; the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) is directly or indirectly responsible for other programs such as meting energy efficiency and renewable targets; the California Energy Commission (CEC) is responsible for longer term planning and forecasting while California Independent System Operator (CAISO) is mandated to keep the grid reliable and the lights on, no matter what else does or does not happen.

If it weren’t for the fact that there are so many targets and mandates and so little time to achieve them, the individual agencies might have been able to cope. But as is, it is impossible for anyone to meet the target without the assistance of the others – and the state’s multiples of utilities, which includes 3 large vertically integrated ones serving roughly 80% of the customers plus two large municipal utilities and a number of smaller ones that are not directly regulated by CPUC, makes the task even more complicated.

If it weren’t for the fact that there are so many targets and mandates and so little time to achieve them, the individual agencies might have been able to cope. But as is, it is impossible for anyone to meet the target without the assistance of the others – and the state’s multiples of utilities, which includes 3 large vertically integrated ones serving roughly 80% of the customers plus two large municipal utilities and a number of smaller ones that are not directly regulated by CPUC, makes the task even more complicated.

To address these issues, in October 2015, the CEC released a massive report, the Integrated Energy Policy Report (IEPR) looking at many of the challenges facing the state. It offers a glimpse of how difficult it will be for the various agencies to meet the targets, and for the state to keep its economy humming along.

The Governor, however, believes that not only can the multiples of targets be met but it will actually be good for the state’s economy at the end, making it more vibrant and dynamic. Referring to his ambitious green and clean vision during his second inaugural address he famously said,

“Taking significant amounts of carbon our of our economy without harming its vibrancy is

exactly the sort of challenge at which California excels,” adding,

“This is exciting, it is bold, and it is absolutely necessary if we are to have any chance of stopping potentially catastrophic changes in our climate system.”

The governor clearly believes in what he says, and more or less says what he believes. Now in his 4th and most probably last term in office – he was the youngest governor during his first term and is now the oldest – Brown dismisses his critics as mere naysayers. How are the targets to be achieved is left to the technocrats and bureaucrats. As far as he is concerned, those are the mere details.

CEC’s IEPR, on the other hand, is focused on the details: how to reach the targets now that they are in place. The starting point – the first chapter of the report – is energy efficiency. There will be less GHG emissions if less energy is used (Figure above).

To make it happen, all sorts of measures, regulations, building codes and appliance energy efficiency standards must be set and enforced. Energy efficiency does not simply happen.

A central component of energy efficiency policy is to encourage the state’s energy utilities, both electric and gas, to meet targets set by the CPUC. But more will be needed, including zero net energy buildings (ZNE), starting 2020 for new residential and 2030 for new commercial buildings.

Considerable space in the report is devoted to decarbonizing the electricity sector, starting with phasing virtually all imported coal generated electricity by 2025 as illustrated in figure below. California has no coal-fired plants within its own borders but historically imported a lot of coal-generated power from its neighbors, a hypocritical practice known as coal-by-wire, which is being phased out over time.

With coal virtually out of the picture, California is focused on increasing its share of renewables, eventually making natural gas as a backup to intermittent renewable generation.

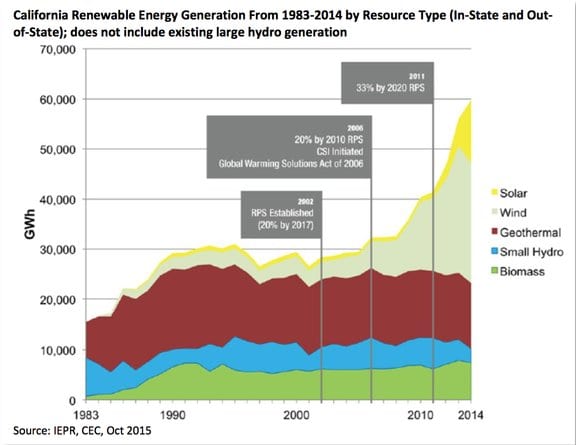

The progress to date has been impressive and SB 350 will guarantee the continued rise of renewables over time. As shown in graph below, a series of successively rising renewable portfolio standards (RPS) passed since 2002, reinforced in 2006, and 2011, culminating with SB 350 in 2015, will increase the share of new renewables to 50% by 2030.

That plus the existing large hydro, geothermal and biomass (components on the bottom of graph on right) means that by 2030 roughly 70% of California’s electricity will be generated from renewables – an impressive feat for the world’s 8th largest economy.

The 3 large IOUs in California already have contracts in place to nearly meet or in some cases beat the 33% RPS target by 2020 as illustrated in table on page 18.

As described in Nov 2015 issue of this newsletter, the most pressing challenge to meet the 50% RPS by 2030 is not lack of renewable generation options – California is blessed with plenty of solar, wind, geothermal, biomass, and other forms of renewable energy – but how to handle the intermittency of large volumes of renewables.

That is why CAISO is looking at a variety of strategies to expand its footprint (map below), one way or another, by relying more on its neighbors to export or import energy as required to keep the grid reliable while absorbing as much as the available renewable generation without resorting to curtailment.

CAISO has already embarked on an expanded energy imbalance market (EIM), which allows some of the state’s excess generation to be shipped elsewhere – and the reverse depending on supply and demand conditions.

Some of California’s neighbors to the East are coal-heavy and do not appear to be concerned about climate change. Governor of coal-rich Wyoming, for example, is a strict non-believer. You would expect that much from the governor of a state that produces more coal than the other 6 major coal- mining states combined.

In this context, California has to find a way to transmit its excess renewable generation and import energy when its own resources fall short without becoming reliant on out-of-state coal- fired generation – which it is trying to get rid of. This is a sensitive – and controversial – issue as the Golden State is essentially forced to embrace its neighbors to balance its increasingly unmanageable intermittent resources, further described in the E3 article (page 13).

De-carbonizing the electric power sector, as difficult as it may seem, is actually the trivial part. The real challenge is what to do with the transportation sector, which currently is overwhelmingly dependent on liquid petroleum products.

On this and other challenges, there is more than plenty to chew on in the latest IPER including revised estimates on the potential impact of self-generation on utility sales. CEC figures customer self-generation, mostly through solar rooftop PVs, will reduce state-wise utility retail sales by more than 35,000 GWhs by 2025, an increase of 12,000 GWHs since the 2014 projections (graphs next page). That represents roughly 12% of statewide retail sales by 2025, depending on which scenario is assumed.

As described in related article on page 6, there are mounting pressures to modify California’s retail tariffs not only in response to the growth of intermittent renewables, but also to deal with the potential death spiral scenario.

Governor Brown, like many others in the arid Southwest, is seriously concerned about the impact of a changing climate on the state’s meager water resources. As recently as 1950, California’s massive hydroelectric system generated 60% of the total consumption. But there are few places left to dam, plus the fact that the state’s

population and demand have more than quadrupled since 1950.That plus the dwindling rain and snowfall have reduced the hydro’s share to around 14% today.

That suggests that water, more than power, will become the dominant theme in arid California and neighboring Southwest in the coming decades. A changing climate, especially one that is drier, warmer, and drops less snow in the mountains, will not be good for California’s power system or its critical agriculture sector.

Perry Sioshansi is president of Menlo Energy Economics, a consultancy based in San Francisco, CA and editor/publisher of EEnergy Informer, a monthly newsletter with international circulation. He can be reached at [email protected]