The global fossil fuel industry faces a loss of $US28 trillion ($A30.2 trillion) in revenues over the next two decades, if the world takes action to address climate change, cleans up pollution and moves to decarbonise the global energy system.

The assessment, made by leading European broking house Kepler Chevreux, underlines what’s at stake for the fossil fuel industry from a push to cleaner fuels and concerted efforts to reduce emissions, and helps explain the enormous push back from the oil and coal industries in particular against such policies.

The Kepler Chevreux report, led by Paris-based analyst Mark Lewis, a former head of Deutsche Bank’s carbon and energy team, says the oil industry has most to lose, with the potential loss of $US19.3 trillion in revenues from 2015 to 2035. The coal industry stands to lose $US4.9 trillion, while the gas industry $US4 trillion.

The latter two markets have particular implications for Australia, which is among the world’s largest exporters of LNG and thermal coal.

The most at risk projects are the high cost, high carbon sources – particularly deepwater drilling, oil-sands and shale-oil plays –which rely on high prices for oil.

Kepler Chevreux arrives at its primary conclusions by comparing the forecasts included in the International Energy Agency’s “New Policies Scenario”, which is effectively business as usual, and what would be needed to meet the 450 Scenario, the parts per million level seen as a benchmark for capping global warming to a maximum 2°C. These graphs below illustrate the emissions reduction path, and the IEA’s estimate of how this might affect production of various energy sources.

But Kepler Chevreux says that its predictions do not rely on there being a global climate agreement struck in Paris at the end of 2015. It says trillions of dollars are still at risk from unilateral and regional action, pollution controls such as those being implemented by China, and the falling of cost of renewables, which will likely displace more coal, gas and oil production.

But Kepler Chevreux says that its predictions do not rely on there being a global climate agreement struck in Paris at the end of 2015. It says trillions of dollars are still at risk from unilateral and regional action, pollution controls such as those being implemented by China, and the falling of cost of renewables, which will likely displace more coal, gas and oil production.

“The oil industry’s increasingly unsustainable dynamics … mean that stranded-asset risk exists even under business-as-usual conditions,” Kepler Chevreux writes. “High oil prices will encourage the shift away from oil towards renewables (whose costs are falling) while also incentivising greater energy efficiency.

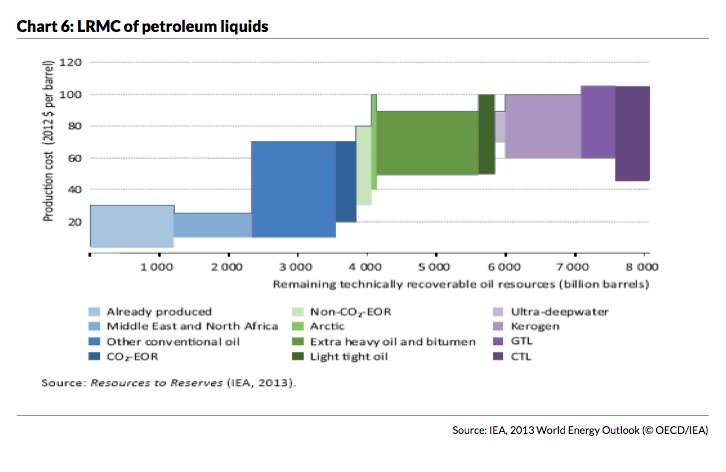

This graph below illustrates the problem. Much of the existing production is low to medium cost, but the remaining reserves – such as those locked under the Arctic, and in complicated and deep reserves, are all expensive to extract.

On this point, the report reflects the majority view of leading investment houses, including Citigroup’s latest assessment that the “Age of Renewables has begun” on the basis of costs, and Sanford Bernstein’s recent warning that the world faced a scenario of energy price deflation because of the impact of the plunging cost of solar, and its likely displacement of fossil fuels across the world.

On this point, the report reflects the majority view of leading investment houses, including Citigroup’s latest assessment that the “Age of Renewables has begun” on the basis of costs, and Sanford Bernstein’s recent warning that the world faced a scenario of energy price deflation because of the impact of the plunging cost of solar, and its likely displacement of fossil fuels across the world.

Some of these stranded asset scenarios are already playing out in Australia. The prospect of energy price deflation could have an impact on LNG projects planned and under construction, as well as the mega projects planned for the Galilee Basin. Independent analyst Tim Buckley recently suggested that Australia’s biggest coal infrastructure project was already at risk, and the soaring price of gas is also sidelining generators and forcing write downs.

According to The Australian, the Energy Supply Association of Australia commissioned a report from Lewis (before he joined Kepler Chevreux) that shows $4 billion of Australia gas-fired generation assets at risk. The ESAA is using this research to argue for the renewable energy target to be dumped, while renewable energy developers say renewable energy will protect consumers from soaring gas prices.

The global fossil fuel industry has been clinging grimly to the IEA’s New Policies scenario, seeking to justify – to both shareholders and bankers – the huge investment it is making in exploration and ever-more capital-intensive projects.

Kepler Chevreux is particularly critical of ExxonMobil’s recent carbon risk report, saying it had focused almost exclusively on business-as-usual scenarios, and “did not advance the debate at all.”

The report says that most existing production – be it in oil, gas or coal – are not at risk. The production at risk are the proven reserves that yet to be developed. As Citigroup and others, including HSBC and Deutsche Bank have previously noted, these proven but as yet undeveloped assets form a significant part of some company’s market and asset valuations.

On the subject of renewables, Kepler Chevreux says tremendous cost reductions have been achieved in recent years, and this is likely to continue over the next two decades – just as the upward trajectory for oil costs becomes steeper.

“This suggests, perhaps paradoxically, that there could be a real risk to the oil industry from rising oil prices under a BAU scenario, as combined with continuing reductions in the costs of renewable technologies this could drive the accelerated substitution of oil in the global energy mix over the next two decades,” it writes.

“In turn, this would risk creating stranded assets over the medium to longer term both for the oil industry itself and – owing to the central role of oil in energy pricing more generally – for the global fossil-fuel industry as a whole.

“The implications of such a scenario would be momentous, as it would mean that the oil industry potentially faces the risk of stranded assets not only under a scenario of falling oil prices brought about by the structurally lower demand entailed by a future tightening of climate policy, but also under a scenario of rising oil prices brought about by rising demand under increasingly constrained supply conditions.”

Not that the oil industry is taking much notice. Most of the major energy forecasts rely on the IEA’s New Policy Scenario. The broking house is particularly critical of the oil industry’s clinging to business as usual forecasts

For this reason Kepler Chevreux is highly critical of ExxonMobil’s recent report on how it was managing carbon risk. The broking house said Exxon was too focused on business as usual, was dismissive of the risk of a co-ordinated global policy response ever happening; and far too “binary” in its assessment of the climate-policy risks the oil industry faces.

“We have already acknowledged that a 450-ppm deal by December 2015 does not look at all likely, but the point about global climate policy is as much the direction of travel as the speed.

“And in effectively dismissing the likelihood of policymakers ever getting genuinely serious in terms of policy ambition, we think ExxonMobil is giving itself a free pass in terms of the need to at least contemplate what a 450-ppm world would mean. It said ExxonMobil “did not advance the debate at all” but it did signal the importance of engaging investors and bankers in the debate.

It notes that certain kinds of investments – notably high-cost, high carbon assets such as Canadian oil sands – could become socially unacceptable as investments for growing numbers of institutional investors over time. Indeed, this was one of the assets explicitly cited by shareholders that forced Exxon to write its carbon risk report.

“We can also envisage a risk of stranded assets arising for oil companies under a scenario of rising oil prices,” Lewis writes.

“Specifically, if oil prices rise faster in future than currently assumed by the IEA in its base-case projections, we think this could lead to an acceleration of the policy incentives for, and deployment of, renewable-energy technologies and energy-efficiency measures, and hence a faster shift away from oil in the global energy mix over the next three decades than ExxonMobil assumes.?