The story we published on Friday comparing the costs of new nuclear, now that they have been defined by contract signed by the UK Government for the construction of the $24 billion Hinkley C facility – with clean energy alternatives such as wind and solar, certainly generated a lot of interest, and comment.

Since then, we have received an analysis from Deutsche Bank, which makes some other observations about the cost of nuclear, the comparisons with gas, the price of abatement, and the cost of upkeep for France’s existing fleet.

The first point made by Deutsche is that this deal underlines the fact that nuclear is not cheap, but really, really expensive – a point that should not be forgotten in Australia, where there is still a push for nuclear in some quarters despite the abundant alternatives (in particular solar) that are not available to the UK.

As we have noted in the other article, the £92.50/MWh strike price is nearly double the current average cost of generation in the UK. Deutsche takes issue with the UK government’s claim that the contract is “competitive with other large-scale clean energy and with gas’. It notes that this contract would only be cheaper than gas generation if the crude oil price (to which UK gas is linked) averages more than $150 barrel in real terms over the next 40 years. This, says Deutsche Bank, is around 3 times the average oil price over the last 40 years, and a 50 per cent premium to the average oil price over the last 5 years.

“Such comparisons do not show that this nuclear contract will be more expensive than gas generation (in 40 years), since conditions in the future may be very different from those of the past,” the Deutsche analysts write. “ However it does demonstrate that signing the proposed nuclear contract would commit the UK to buying electricity which would be expensive by historic standards.” It later describes the 35 year contract as “a poor trade for reducing risk.”

Then Deutsche Bank looks at the carbon cost of nuclear. It calculates that if the oil price were to remain at the current level of $100/barrel (in real terms), the cost of gas generation would be around £68/MWh (before paying for carbon emissions). Taking into account the amount of carbon emissions saved and the extra generation costs of nuclear, the nuclear generation comes at an implied cost of £65/tonne of carbon dioxide saved.

It notes that this carbon cost is more than ten times higher than the current traded price of carbon emissions in the EU ETS, is roughly twice the targeted level of the UK carbon price floor in 2020 set out by the Treasury in December 2011 (£30/tonne in 2009 prices), although it is less than the £70/tonne price floor envisaged in 2030.

It says that nuclear is only justified in the UK if the government is serious about largely decarbonising the electricity grid by 2030, as has been canvassed by the UK’s Climate Change Council – the UK equivalent of the Climate Change Authority that Tony Abbott wants to disband. Deutsche notes that it does not meet UK’s short term needs to meet its 2020, which likely be met with more wind and biomass.

The CCC envisaged several scenarios to cut the UK’s carbon emissions to 50g/CO2-eMWh by 2030. The first scenario, see graph below, envisages 18GW of new nuclear. Deutsche Bank says this would require 5 more new nuclear facilities the size of Hinkley to be built within 16 years – not only is such a target “hugely ambitious”, Deutsche says it would still be “not be nearly enough in itself to meet such a decarbonisation target.”

The UK would need at least as much wind generation as nuclear, and some low-carbon flexible generation. Deutsche also notes that CCS is highly ambitious, as the technology is not proven, which leaves the most likely scenarios as being high renewables, or high energy efficiency, both of which leave wind and other renewables providing more than 50 per cent of the UK’s generation by 2030.

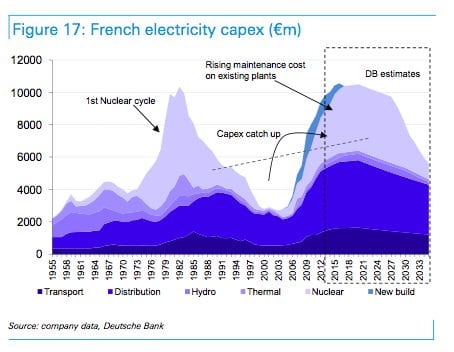

And just in case anyone feels like arguing that it is just new-build and new generation nuclear that is costly, this graph below should blow a few misconceptions.

It’s another from the Deutsche Bank team, and it shows the estimated capital expenditure requirement for the EdF fleet of nuclear reactors in France. Note that it is significantly higher than the original cost of the reactors in the 1970s and 1980s. Deutsche Bank says consumer electricity prices are being jacked up to meet some of that cost, but it estimates that EdF will need to spend €55 billion ($79 billion), a situation that will leave it in a cash-flow negative situation (It already has an €85 billion debt).

As Deutche Bank noted, any investment in new reactors would need to be funded on top of the refurbishment budget. Given that it is already cash-flow negative and has such a huge debt, few people have any clue how that could possibly be done. Which is why EdF’s major shareholder, the French government, is looking to reduce the share of nuclear in France’s generation to around 50 per cent from more than 70 per cent, and intends to fill that hole with (cheaper) renewables.

Still, Deutsche Bank notes that EdF has effectively handballed the risk of new nuclear to consumer and the UK government. The consumer is picking up the tab through higher electricity bills, and the UK government is using taxpayers money to guarantee 65 per cent of the project cost. With the involvement of Chinese nuclear interests, that leaves EdF with an exposure of just £3.5 billion.