Inside Climate News

LONDON – Hard on the heels of the latest UN report on climate change, two UK scientists have proposed an ambitious plan to tackle the problem it graphically describes.

Their solution? A massive and urgent international program to increase the world’s production of solar energy – to 10 percent of total global energy supply by 2025, and to 25 percent by 2030.

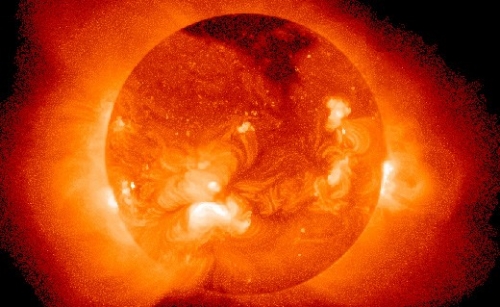

Credit: NASA Goddard Laboratory for Atmospheres

The scientists, David King and Richard Layard, say their proposal – which they call a Sunpower Program – should within little more than a decade be producing solar electricity which costs less than fossil fuel power.

They write in the online Observer: “The Sun sends energy to the earth equal to about 5,000 times our total energy needs. It is inconceivable that we cannot collect enough of this energy for our needs, at a reasonable cost.”

Last week the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC, published the first section of its Fifth Assessment Report, called AR5 for short. It said: “Limiting climate change will require substantial and sustained reductions of greenhouse gas emissions.”

Sir David King was formerly chief scientific adviser to the UK Government, and Lord Layard is the founder-director of the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics.

They write: “There will always be many sources of non-carbon energy – nuclear fission, hydropower, geothermal, wind, nuclear fusion (possibly) and solar.

“But nuclear fission and hydropower have been around for many years. Nuclear is essential but faces political obstacles and there are physical limits to hydropower. Nuclear fusion remains uncertain.

“And, while wind can play a big role in the UK, in many countries its application is limited. So there is no hope of completely replacing fossil fuel without a major contribution from the power of the Sun.”

Time ‘desperately short’

They recognize the progress being made already: “The price of photovoltaic energy is falling at 10 percent a year, and in Germany a serious amount of unsubsidized solar electricity is already being added to the grid. In California, forward contracts for solar energy are becoming competitive with other fuels and they will become more so, as technology progresses.”

Credit: The Sky is Not the Limit/Flickr

But time, they say, is “desperately short” – and there are two significant scientific challenges to be overcome: cloudy days and sunless nights, and the cost of sending the electricity produced – in areas with plenty of sunshine but few people – to where it is needed.

The first, they say, needs a major breakthrough in battery science, while the solution to the transmission conundrum needs new materials which are much better at conducting electricity without loss of power.

A German group, Desertec, announced plans to produce solar energy in the Middle East and North Africa and to transmit the surplus to Europe. It identified both the problems King and Layard have recognized, but the scheme was reported in July to have collapsed, partly because of market skepticism.

The authors acknowledge that their proposal amounts to “a major scientific challenge, not unlike the challenge of developing the atom bomb or sending a man to the moon”.

And they believe this challenge is also surmountable: “Science rose to those challenges because a clear goal and timetable were set and enough public money was provided for the research. These programs had high political profile and public visibility.

“They attracted many of the best minds of the age. The issue of climate change and energy is even more important and it needs the same treatment.”

Source: Inside Climate News. Reproduced with permission.