ITK principal and Energy Insiders podcast co-host David Leitch is not greatly bothered greatly by high electricity market prices. It is, he likes to say, and often does, the most effective signal for developers of new projects to get them built.

Australia’s energy regulators and rule makers clearly agree. It’s why they have lifted the market price cap to above $20,000 a megawatt hour – not because of the cost of technology, but as a strong signal for plant to stick around or for new ones to be built.

And haven’t these facilities cashed in over the past week as the heatwave cooks the country, particularly in South Australia earlier this week.

The developers of battery storage are also pondering market signals as they weigh the financial modelling of their proposed projects. There is clearly not enough battery storage in the grid yet to fully support a transition from coal and gas, but already their margins are being crunched at times because of too much capacity in some key periods.

The latest Quarterly Energy Dynamics report from the Australian Energy Market Operator tells such a story for the December quarter.

The rapid growth of big battery storage has clearly displaced coal and gas in a major way, particularly in the evening peaks, on both Australia’s main grid – the National Electricity Market (NEM) – and the separate W.A. grid, known as the WEM.

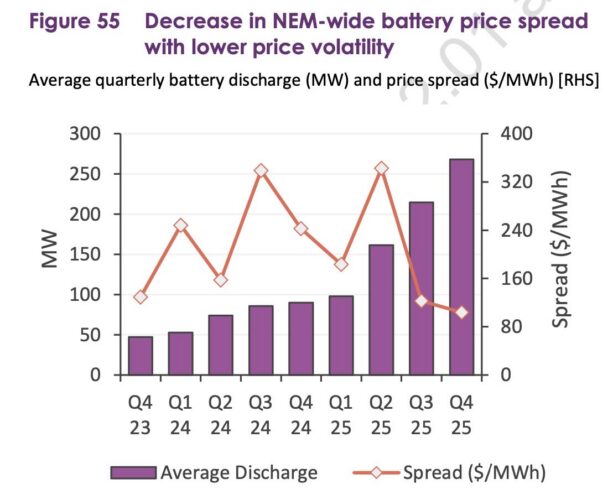

As AEMO notes, battery storage dispatch capacity increased three fold over the last 12 months, but in the December quarter revenues from market arbitrage and frequency control increased by a mere $1 million.

The reason for this was a significant decline in market price spreads, the difference between the cost of charging the batteries and the price received for discharging them (minus also the power lost in the round trip).

According to AEMO, the price spread shrank by 57 per cent from $243/MWh in Q4 2024 to $104/MWh in 2025.

“This narrowing of price spreads explains the relatively modest increase in total battery earnings from energy arbitrage, despite the very strong growth in battery capacity and output,” AEMO notes.

It notes that different states told different stories. Growth in energy arbitrage revenue was concentrated in Victoria and South Australia, where revenues increased by $13.5 million and $7.5 million, respectively.

But arbitrage revenue declined significantly in the country’s two most coal dependent states, Queensland and NSW, by $3.6 million and $4.1 million. The price spread shrank by 74 and 77 per cent in those two states.

Of course, this is not the end of the road for battery storage. For a start, market volatility will return, particularly in summer heatwaves and as more thermal plant is retired.

The recent experience of South Australia, where market prices surged to more than $20,000/MWh for several hours as the big batteries ran out of charge, shows there is still room for growth.

And big batteries have other revenue opportunities too. The biggest batteries in the country have lucrative contracts acting either as “solar soakers” – Neoen’s Collie battery and others – or giant shock absorbers (Waratah Super Battery and the Victoria Big Battery).

Other revenue streams are also emerging – acting as virtual transmission (such as the Darlington Point battery), and also targeting potential markets for inertia and system strength – the key system security services now provided by coal and gas that will have to be replicated and batteries and synchronous condensers.

There is also a key role as part of soalr-battery hybrids – storing excess power from an adjoining solar farm so they can send power to the grid in the more lucrative evening peaks – a popular choice now emerging thanks to plunging battery prices and new connection rules.

And there is also the “portfolio factor”. Many of the key legacy generation companies are now building and contracting big battery projects – often at the site of their ageing coal and gas generators – because they reason they are a more flexible and even cheaper asset to deploy at peak times.

After all, if you can discharge a battery in the evening peak, when prices can leap above $300/MWh, why crank up a diesel generator whose fuel costs will eat up most of that margin. Ok, maybe one diesel generator, just to make sure the price gets there.

If you would like to join more than 29,000 others and get the latest clean energy news delivered straight to your inbox, for free, please click here to subscribe to our free daily newsletter.