Call it an act of the greatest folly, or simply one of greed. But it seems that the world’s energy companies are hell-bent on spending up to $6 trillion of shareholder funds and bank debt in the next decade on fossil fuel investments – assets that could well become stranded and worthless if the world acts to limit climate change.

This is the conclusion of a new report on the so-called “Carbon Bubble”, which highlights the fact that the bubble is getting bigger. It now estimates that between 60 and 80 per cent of the coal, oil and gas reserves of publicly listed companies could be classified as unburnable if the world is to achieve emissions reductions that offer the greatest chance of limiting average global warming to 2°C.

Research by Carbon Tracker and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at London School of Economics and Political Science shows that 200 major listed companies own 762 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) through their reserves of coal, oil and gas. These reserves currently supports share value of $4 trillion and service $1.5 trillion in outstanding corporate debt.

But to achieve emissions reductions consistent with an 80 per cent chance of achieving the 2°C target, the fossil fuel reserves of these listed companies would likely have to comply with a budget of just 125 billion tonnes to 275 billion tonnes of CO2. That means cutting them by three quarters or more, even more than that estimated last year by the International Energy Agency.

To make matters worse, a further $674 billion was invested in new fossil fuel investments in 2012, and at the current rate more than $6 trillion will be invested over the coming decade – much, or even all of which could become stranded assets.

The research is delivered as a warning to asset managers, shareholders and bankers, but it comes in the same week that the principal market signal on climate change action, the international carbon price, plunged to new lows in Europe after the failure of the EU parliament to solve the damaging impact of a huge surplus of free and unused carbon credits.

The collapse of the carbon price is being painted as a failure of the market based system, when in fact it is really a failure of political will. In Australia, true to form, the mainstream media has been led by the political spin-doctors to focus on what amounts to economic trivia – the impact that a lower carbon price could have on forward estimates of budget revenues.

The larger and most significant implications, that of the need for companies to have an incentive to invest in action to decarbonise one of the world’s most emissions-intensive economies, is largely ignored. And don’t think that corporate Australia is not stupid enough to ignore what is clearly one of the key global mega-trends. The speech by Tony Shepherd, the chair of the Business Council of Australia, was confirmation of that – recognizing that Australia’s response to climate change was somewhere between “half-hearted and non-existent”, but at the same time calling on the government to effectively dismantle the very schemes that encourage the required investment.

Too many in corporate Australia will use any excuse to avoid the inevitable, in the interest of short term returns, and this has become the de-facto policy of the Coalition government-in-waiting, which has upped its calls to scrap the whole idea of a carbon price. Analysts say this is a really bad idea, even if you are supposedly concerns about short term “competitiveness.” It was interesting that Chinese authorities were making clear overnight that the European price collapse would have no impact on its own plans for an ETS.

The Carbon Tracker research may appear dramatic, but the concept of a carbon bubble is steadily gaining traction among funds managers, analysts, and advisors. Apart from the IEA clarion call last year, Citi last month reached a similar conclusion about the potential impact of concerted climate action, depending on its timing. It noted that fossil fuel companies would be motivated to extract their assets as quickly as possible – an action that the BCA seems happy to endorse, and facilitate.

Professor Lord Stern of Brentford, chair of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, and he of the eponymous report on climate economics, said smart investors can already see that most fossil fuel reserves are essentially unburnable because of the need to reduce emissions in line with the global agreement by governments to avoid global warming of more than 2°C.

“They can see that investing in companies that rely solely or heavily on constantly replenishing reserves of fossil fuels is becoming a very risky decision. But I hope this report will mean that regulators also take note, because much of the embedded risk from these potentially toxic carbon assets is not openly recognized through current reporting requirements.”

Stern said that the report raises serious questions as to the ability of the financial system to act on industry-wide long term risk, since currently the only measure of risk is performance against industry benchmarks.

Paul Spedding, an oil and gas analyst at HSBC, said described the scale of unburnable carbon assets in listed companies as “astonishing”, and added ‘business-as-usual’ is not a viable option for the fossil fuel industry in the long term.

“Management should already be looking to new business models that reduce the risk of stranded assets destroying shareholder value, In future, capital allocation should emphasise shareholder returns rather than investing for growth,” he said

Jens Peers, chief investment officer for Sustainable Equities at MIROVA, was even more damming. “It is still shocking to see the numbers, as they are worse than people realise. It is frightening that risk is not properly distributed and this needs to be cleaned up.”

He said the research should act as a wakeup call for asset managers who put too much emphasis on the short term. “Asset managers who think they have time to adjust have the wrong attitude and our evaluation theory is too short term. They are either naïve and do not see this as an issue, or they know about it but wrongly assume a technology will clean it up, not taking responsibility or seeing this as a risk they have to pay for.”

Although the conclusions from the Carbon Tracker report seem bleak, it insists it applied an optimistic scenario to stress-test the carbon budgets. This assumed that more effort was applied to non-CO2 emissions, (e.g. methane from waste and agriculture), which resulted in freeing up more CO2 budget for fossil fuels.

This approach indicates a carbon budget for an 80% chance of avoiding global warming of more than 2°C is about 900 billion tonnes up to 2050, and about 1,075 billion tonnes for a 50% chance. However under a more precautionary scenario, the carbon budget could be around half this amount – 500 billion tonnes. This results in the range of 60-80% of total reserves being in excess of the 2°C budget. Here are two tables to illustrate this, the first giving the allowable budget out to 2049 under various scenarios, and the second from 2050 to 2100

But it found that even if CCS is deployed in line with an optimistic scenario by 2050, fossil fuel carbon budgets would only be extended by 125GtCO2, allowing the equivalent to 4% of current global reserves to be burned as long as their emissions are captured and stored. Beyond 2050, the total carbon budget is very small for a 2°C target, which means that reserves will remain unburnable during the second half of the century unless there is a dramatic development of CCS after 2050.

What’s more, the analysis found that even under a less ambitious climate goal, like a 3°C rise in average global temperature or more, would still imply significant constraints on the use of fossil fuel reserves between now and 2050.

“Current extractives sector business models are based on assumptions that there are no limits to emissions,” the report notes. “The current balance between funds being returned to shareholders, capital invested in low-carbon opportunities and capital used to develop more reserves, needs to change. The conventional business model of recycling fossil fuel revenues into replacing reserves is no longer valid.”

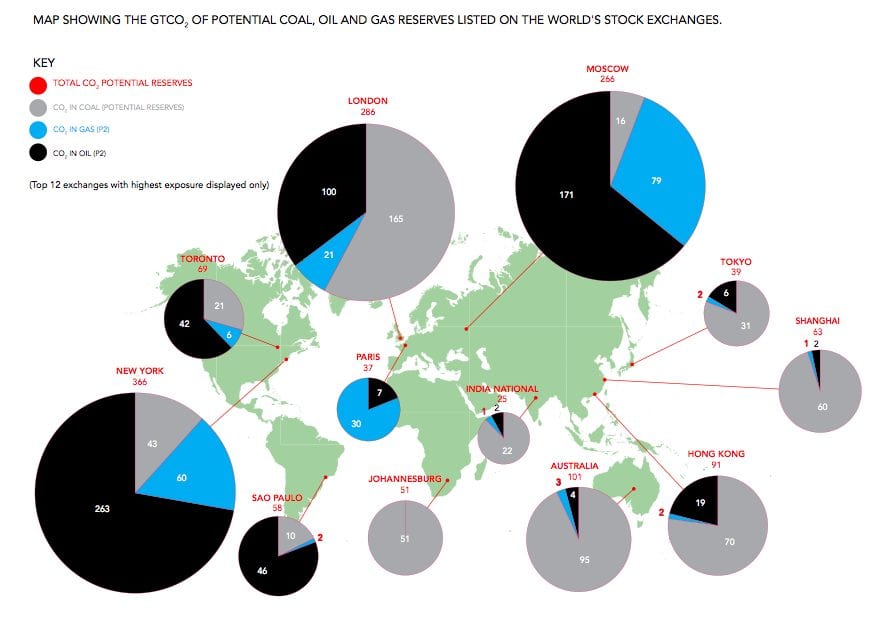

It also highlights which of the world’s stock exchanges may have the greatest exposure. The table below provides an illustration. New York, Moscow and London have high concentrations of fossil fuels on their exchanges, and if the reserves on the Hong Kong, Shanghai and Shenzen exchanges are combined then China is not far behind.

But it also noted that Australia, Johannesburg, Tokyo, Indonesia, Bangkok and Amsterdam would all see their levels more than triple if the current prospects have more capital invested and are successfully developed into viable reserves. It said investors and regulators should start questioning the validity of new or secondary share issues by companies seeking to use the capital to develop further fossils, a call recently echoed by Moody’s and S&P, which questioned the credit quality of some of these companies.