With a lot of exaggerated fanfare, in early May 2024 the Georgia Power Company announced that the 1,114 MW Unit 4 nuclear power reactor at Plant Vogtle near Waynesboro, Georgia, entered commercial operation after 11 years of construction.

The former CEO of the company reportedly had installed a TV screen in his office remotely monitoring the progress of the work at the construction site. It must have been the most boring show to watch since on most days very little was actually happening at the site. He was mostly watching delays.

Vogtle unit 3 began commercial operation in July 2023. The plant’s first two older reactors, with a combined capacity of 2,430 MW, began operations in 1987 and 1989, respectively. The Plant Vogtle’s total generating capacity is nearly 5 GW surpassing, the 4,210-MW Palo Verde nuclear plant near Phoenix in Arizona.

Construction of the last 2 reactors began in 2009 and was originally expected to cost $US14 billion with a start date in 2016 and 2017. But as often happens the project suffered construction delays and cost overruns – exceeding $US30 billion ($A45 billion).

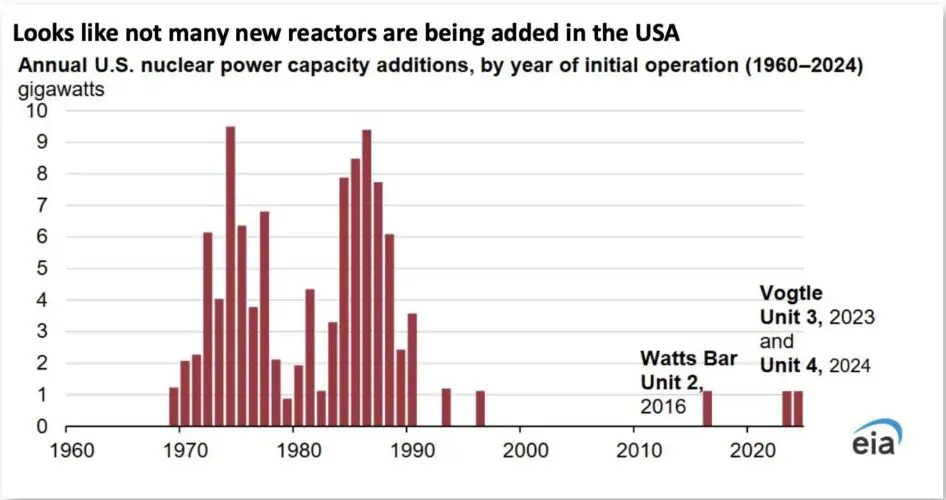

It is the latest – and possibly the last – addition to the US nuclear installed capacity, which is currently around 97 GW and accounted for nearly 19% of domestic electricity production in 2023, making it the second-largest source of electricity generation after gas, which was around 43% last year.

Vogtle Units 3 and 4 use the Westinghouse AP1000 design (cited enthusiastically by Australian opposition leader Peter Dutton this week) which includes new passive safety features that allow the reactors to shut down without any operator action or external power source.

Two similar reactors were planned for South Carolina, but the utilities halted construction in 2017 amidst escalating costs and delays.

The Executive Director of American Nuclear Society (ANS) Craig Piercy congratulated Southern Company, the parent of Georgia Power Company, and Westinghouse:

“This milestone … secures a generational investment in clean energy. Now complete, Vogtle 3 and 4 will deliver 17 million MWhrs of carbon-free power to Georgia annually – equivalent to the energy from all California’s wind turbines – and will be available 24/7.”

Fair enough but Mr. Piercy failed to mention that it took 11 years and $US30 billion of ratepayer money to build it – few private investors can afford the time or the capital.

Nor did he mention that currently there are no other nuclear reactors under construction anywhere in the US and none are presently contemplated. It may be the end of an era despite ANS’ obviously biased praise of the technology.

The story is much the same in France where the state-owned nuclear power giant Électricité de France (EDF), which operates a fleet of 56 reactors in one of the most nuclear dependent countries in the world, has been struggling to complete its last reactor.

The 1.6 GW Flamanville plant in northwest France is 12 years behind schedule and more than four times over budget – for the usual reasons. A faulty vessel cover needs to be fixed, pushing operation date to 2026.

In the meantime, the estimated cost to construct 6 new nuclear reactors, ordered by President Emanuel Macron, has risen to €67.4 billion ($A110 billion), from the original €51.7 billion, and is likely to go higher before they are completed. Nuclear plants are not cheap.

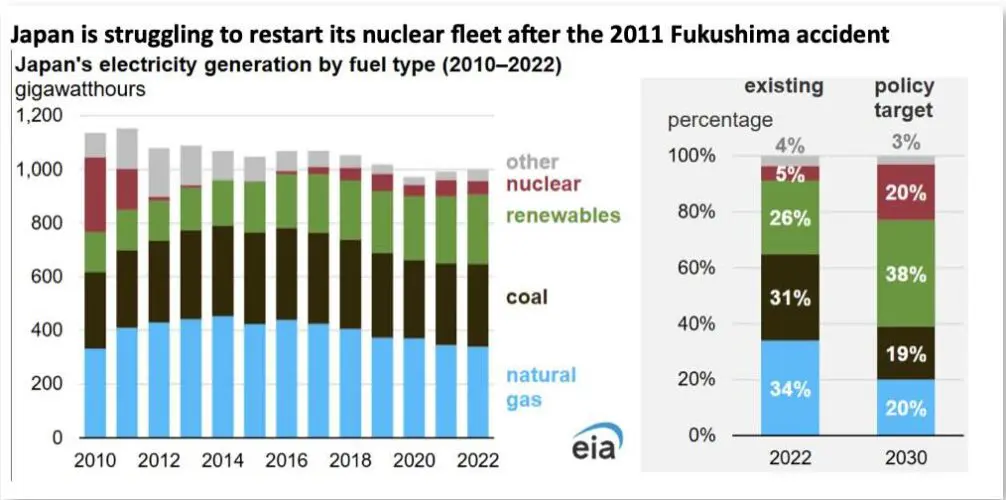

At the same time, the Japanese government, which aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, is focusing on lowering emissions in the electric power, industrial, and transportation sectors. In the electric power sector, government policies have set targets for 2030, which include accelerated investment in renewable capacity, increased nuclear generation, and reduced use of fossil fuels (visuals above).

Before the Fukushima accident in 2011, nuclear power accounted for about 30% of Japan’s electricity mix with plans to increase it to over 40% by 2017. Following the accident the government suspended operation of all nuclear reactors for inspections and safety upgrades. It restarted 2 reactors in 2015 after they passed safety checks followed by 2 more in 2024 and the rest to follow.

Japan will need 24 GW of operating nuclear capacity to meet the target of 20-22% nuclear generation by 2030. By the end of 2024, 12.6 GW is expected to be operating.

One of the few places where new reactors are being built without long delays is China, but even there the scale of nuclear build is dwarfed by solar and wind by orders of magnitude.

In the past 10 years, more than 34 GW of nuclear power capacity were added in China, bringing the country’s number of operating reactors to 55 – barely shy of the 56 in France – with net capacity of 53.2 GW as of April 2024 (visual on right). Some 23 reactors are reported under construction in China.

The US, of course, has the largest nuclear fleet, with 97 reactors, but it took nearly 40 years compared to roughly a decade for China. Despite the ambitious pace of growth, nuclear accounts for barely 5% of China’s power output compared to roughly 19% in the US and 70% in France.

As a point of reference, China added around 20 GW of coal in 2022 bringing its total coal-fired capacity to 1,089 GW. And there lies the challenge if China, currently the biggest global carbon emitter – is to trim its greenhouse gas emissions. It will need a lot more renewable, hydro and nuclear and a lot less coal and natural gas.

Globally, nuclear, while a low-carbon and baseload form of generation, is struggling to make much of a dent despite a few isolated places where it is maintained on the agenda – generally by government fiat and through generous subsidies.

It is hard to come up with a conceivable scenario where its fortunes will significantly improve. A hefty global carbon tax, for example, may help but even in this case, it will simply make renewables, not nukes, even more attractive than they already are.

Fereidoon Sioshansi is editor and publisher of EEnergy Informer, and president of Menlo Energy Economics, based in California.